What’s Going On With Our Water?

A comprehensive examination of the issue

By Brian Almon

Figuring out how to acquire and use water has been a concern of the human race since the beginning. The Bible records an interaction between the patriarch Isaac and a Philistine king over wells drilled by Isaac’s father Abraham. The film Lawrence of Arabia dramatized a moment in that same region in which an Arab kills another man for the crime of drinking from his well.

Water is life, and a lack of water means death and desolation. In our modern world, which is essentially post-scarcity as far as the average American is concerned, it is easy to forget that water is not an infinite resource. It was for that very reason that the framers of our state constitution declared the use of water to be subject to state control. Ideally, we would all share common resources such as water, but what happens when there’s not enough to go around?

On May 10 of this year, the Idaho Dept. of Water Resources (IDWR) notified several thousand farmers in eastern Idaho that they faced potential curtailment of their access to water due to an expected shortage. To avoid curtailment, water users had to join a groundwater district that had an approved mitigation plan which promised to cut back on usage in order to allow the Eastern Snake River Plain Aquifer (ESPA) to recharge. This was done according to a 2016 mitigation agreement.

On May 30, IDWR director Mathew Weaver issued curtailment orders to users in six groundwater districts without approved mitigation plans. This set off a firestorm on social media. A video posted by the account Wall Street Apes on June 9 warned that curtailment would shut off water to 500,000 acres of farmland went viral, reaching 2.9 million views as of this writing. The video was an excerpt of a video from the YouTube channel Yanasa TV posted on the previous day which examined both sides of the curtailment order:

However, the excerpt posted on Twitter only showed one side of the story, which led to thousands of people flooding social media with warnings that Gov. Brad Little was unilaterally destroying Idaho farms, probably at the behest of Bill Gates and the World Economic Forum. Concurrent news about a cobalt mine near Salmon that was recently allocated money via a Ukraine aid package raised more eyebrows, as people began connecting the two. Was our government shutting down water to farmers so as to send it to a cobalt mine operated by foreign firms?

In short, no. Idaho Cobalt Operations (ICO), operated by an Australian company called Jervois, is in the Salmon River watershed, more than a hundred miles from the aquifer used by eastern Idaho farmers. Also, the water used by the cobalt mine for dust suppression and ore processing would mostly come from the drilling operations in the mine itself, without a need to import water from elsewhere in the state.

ICO, the only primary cobalt mine in the United States, was acquired by Jervois in 2019 and prepared to operate in 2022. However, they shut down operations in early 2023 when the price of cobalt fell, likely due to Chinese action in the market. Cobalt is an important element in modern batteries, including electric vehicles. Congress appropriated $15 million to keep the mine ready for operations in order to maintain domestic access to cobalt and not remain reliant on China.

Whether or not ICO is a good investment for Idaho is a topic for another essay. Suffice it to say that its operation is not likely to be related to the water issues in eastern Idaho.

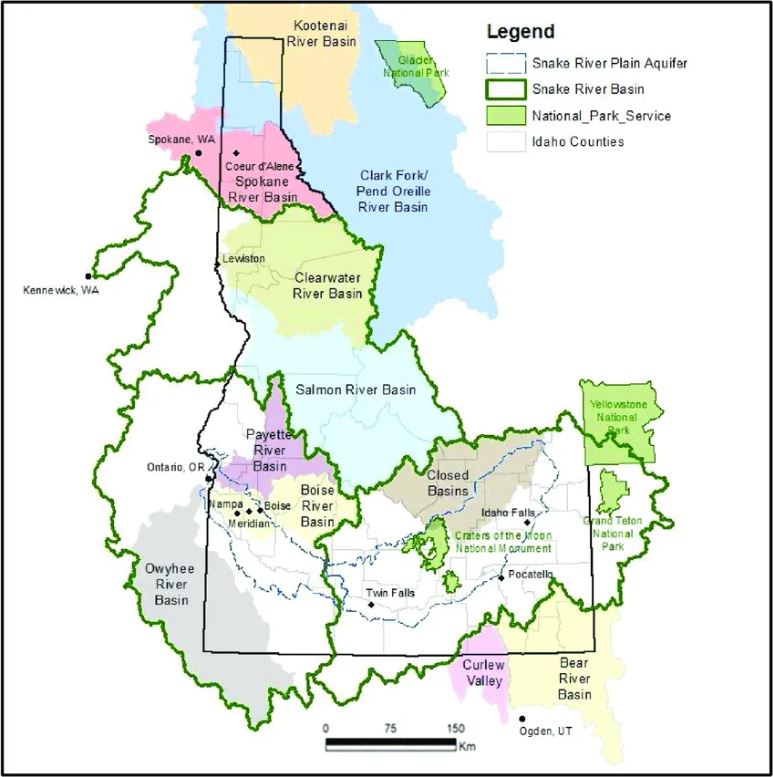

John T Abatzoglou via ResearchGate

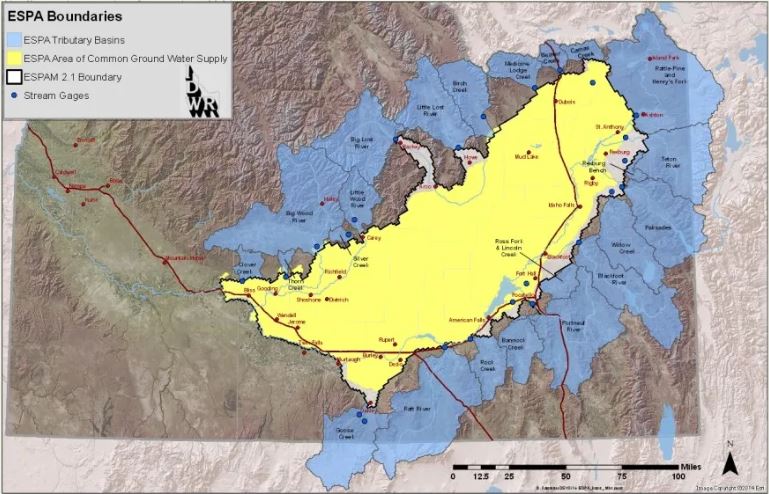

The Eastern Snake River Plain Aquifer runs from approximately St. Anthony in the northeast to Hagerman in the southwest. It is recharged via melting snow in the surrounding mountains. ESPA feeds into the rivers and canals of the Magic Valley, so the amount of water pumped from underground in eastern Idaho can affect the amount of water available to surface water users further west.

To understand the issue, we must first recognize the difference between groundwater and surface water. Surface water refers to, well, water on the surface. That would be rivers, lakes, streams, and irrigation canals. Here in Eagle, we have several canals flowing through the city, diverting water from the Boise River to feed the large farms throughout the region.

Groundwater is water that is stored underground in geological formations called aquifers. Rather than being subterranean lakes, aquifers are like giant underground sponges made up of gravel and sand into which water is absorbed from above-ground sources. The purpose of drilling a well is to access this underground water. Humans have been drilling wells since antiquity, but modern technology has drastically improved safety and efficiency.

Here is a video I found that explains how aquifers work:

We are still figuring out the many ways in which surface water and groundwater are related. Surface water can seep into the ground, recharging the aquifer, while springs can feed surface water as well. One of the claims made in the viral videos is that rivers and reservoirs are full, so how could their possibly be a shortage that demands mitigation or curtailment? The answer is that aquifers recharge much more slowly than surface water, meaning it’s possible to have a full reservoir at the same time as a dwindling aquifer.

For the past thirty years or so, Idaho has been managing groundwater and surface water concerns under a doctrine called conjunctive use. Previously, these two sources of water were regulated separately, but as we learn more about how they are intertwined it makes sense to manage them in such a way that takes that interaction into account.

This is where water rights come into play. Idaho regulates water rights according to a doctrine called prior appropriation, better known as first in time, first in right. Generally this means that whoever began using a water source earliest has first dibs on that water. These water rights are usually attached to properties, so farmers, companies, or individuals inherit them when they purchase new land.

The Twin Falls Canal Company (TFCC) established surface water rights in the early 1900s, prior to much of the groundwater irrigation operations in eastern Idaho. It was TFCC that notified regulatory agencies that they anticipated a water shortage this year, which led to the mitigation and curtailment orders.

Why? TFCC has water rights going back further than eastern Idaho farmers, therefore they are legally considered to have senior rights. The ESPA is one of the largest aquifers in the nation, not only providing groundwater for eastern Idaho but also serving as a source for surface water in the Magic Valley. If too much water is pumped out of the aquifer in eastern Idaho, then the amount that serves TFCC’s canals drops. However, according to prior appropriation, TFCC has first dibs on that water, so they have the legal option to force groundwater users (who have junior rights) in eastern Idaho to cut back or face full curtailment.

Water users in the Magic Valley such as TFCC have organized under the umbrella of the Surface Water Coalition (SWC), while farmers in eastern Idaho organized the Idaho Groundwater Appropriators, Inc. (IGWA). In addition to farms, the SWC also represents fish hatcheries and hydroelectric dams. The current chair of IGWA is Rep. Stephanie Mickelsen of Idaho Falls.

The two groups agreed to a mitigation plan in 2016, mediated by then state representative Scott Bedke, who is now the lieutenant governor. That plan was meant to provide assurance to farmers in eastern Idaho that so long as they maintained a certain level of water in the ESPA, then they would not face any curtailment orders. However, a drought in 2020-21 caused shortages that are still being felt today. Even though reservoirs today are full, IDWR says that aquifer levels are still much lower than they should be, and therefore ordered farmers to comply with the 2016 mitigation agreement.

It seems clear to me that the viral videos are part of a coordinated effort by the IGWA to discredit the SWC and drive public opinion toward changing the way in which Idaho regulates its water. In an address to the City Club of Idaho Falls on May 30, Mickelsen suggested that the current system was unfair to farmers:

The priority doctrine does say we need to beneficially use the resource. And then you end up with this court case that says that basically every canal out there is going to be senior to any groundwater user. So then it puts groundwater users in a perilous situation because now they’re basically kind of controlled by the whims of the surface water canals.

Mickelsen expressed skepticism that senior water rights holders in the Magic Valley were truly experiencing a shortage:

We went up in a helicopter and actually took pictures, and they had 24 or 25 waterfalls, I believe, where water was just booming over the edge of the canyon… And they’re claiming that they’re short!

In another viral video, a pair of farmers who run the Rocky Mountain Farmer YouTube channel shared their perspective on June 19:

According to these farmers, the issue is not due to a potential shortage, but a lack of leadership. Are they correct? Could Gov. Little have simply solved the problem with the stroke of a pen? The governor disagreed. In a press release last week announcing the withdrawal of the curtailment order after all districts had agreed to mitigation plans, Little said:

I have heard repeated calls for me to step in and stop Director Weaver from moving forward in administering the law. Doing so would violate the Idaho Constitution and create a risk of handing control of our water over to the state courts, or worse the federal courts, or worst U.S. Congress. Instead, we chose to work together on a solution.

The governor is correct that the concept of first in time, first in right is embedded in our state constitution:

Whenever more than one person has settled upon, or improved land with the view of receiving water for agricultural purposes, under a sale, rental, or distribution thereof, as in the last preceding section of this article provided, as among such persons, priority in time shall give superiority of right to the use of such water in the numerical order of such settlements or improvements; but whenever the supply of such water shall not be sufficient to meet the demands of all those desiring to use the same, such priority of right shall be subject to such reasonable limitations as to the quantity of water used and times of use as the legislature, having due regard both to such priority of right and the necessities of those subsequent in time of settlement or improvement, may by law prescribe.

Idaho Constitution, Article XV, Section 5

Title 42 of Idaho Code lays out in specific detail how water usage is to be governed. Section 104 explains that water rights can be lost if the owner no longer uses them for a beneficial purpose. To that end, IDWR must prioritize between municipal usage, farms, hydroelectric dams, fish hatcheries, and other beneficial uses of water.

Some suggest that corporations such as TFCC and Idaho Power are manipulating the law for their own gain. I have read several posts on social media as well as longer pieces that accuse these companies of manufacturing a crisis so as to put eastern Idaho farmers out of business and keep all the water for themselves.

Sen. Glenneda Zuiderveld, representing district 24 in the Magic Valley, wrote an editorial in response to the viral videos in which she shared the rest of the story:

The two water rights currently in conflict, as you may have heard in the news, are surface water rights and ground water rights. Surface water rights, which have the most seniority, date back to 1904 when the canal system was created (Senior Water Rights). Ground water rights began in 1947 with the drilling of the first ground water well (Junior Water Rights). More information on water rights click HERE.

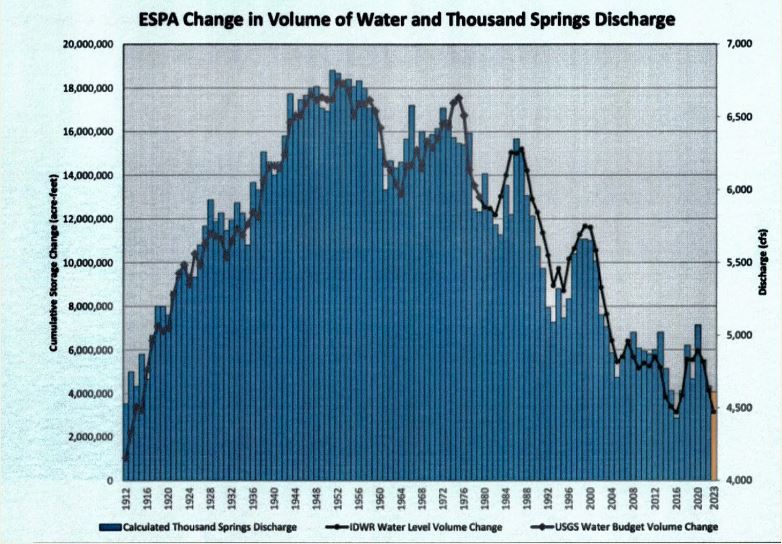

Now that I have explained Idaho water rights and their seniority, let me shed some light on current events. We have been witnessing a decline in our aquifer for decades. One way to measure this is through Thousand Springs in Hagerman, Idaho. The decline in these springs has been evident for a very long time. Today, Thousand Springs is more like Fifty Springs, which should alarm all of us, not just farmers.

Zuiderveld included a graph showing the volume of water discharged from ESPA into Thousand Springs:

As you can see, the amount of water increased substantially after the 1900s, but started decreasing again in the 1950s. Ironically, it was the relatively inefficient watering practices of the mid-20th century that potentially led to the increase, as water that was lost into the ground made its way back into the aquifer.

This mini-documentary by Outdoor Idaho does a good job of explaining the history of water usage in Idaho:

KTVB also posted a short video that laid out the basic situation fairly well in light of the current controversy:

I still see people claiming that water should be free and that eastern Idaho farmers should not have their usage curtailed because of the needs of water users in the Magic Valley. As I said, it’s easy to forget that water is a scarce resource. Adam Smith explained that the beauty of capitalism is that each man contributes to society by acting in his own self interest. A farmer who makes a living raising cattle also benefits his community by providing milk and meat. However, water is a resource that does not respect property lines, which means it is liable to experience the tragedy of the commons.

Property rights are usually fairly straightforward. What’s mine is mine, and what’s yours is yours. However, the aquifer is a common resource beneath every property within the region. If one property owner pumps out all the water, then his neighbors will suffer. Does one property owner have the right to negatively impact his neighbors in such a fashion? I recently read a story from Texas that serves as a warning of where that attitude will inevitably lead:

I went to breakfast one morning with a hydrologist known for his work with landowners marketing their groundwater. While we waited for our food, I laid out the reason I’d gotten in touch with him—how I wanted to tell the story of the interconnection of our waters under the ground with the water above it, so that Texans could figure out how to sustain both.

Our food arrived. He sat patiently and without expression as I continued, both of our plates untouched and steaming. And when I had finished, he silently picked up a pen and began to write out four points. The first, in block letters, was this: groundwater is private property. In Texas, he said, to make the point clear, “the landowner owns everything on his property, from hell all the way to heaven.” That includes the groundwater.

What I learned that day is this: in Texas, no conversation about groundwater has begun until you’ve acknowledged it to be the property of the landowner. Before that, you’re just wasting a perfectly good breakfast.

Unlike Idaho’s prior appropriation doctrine, Texas followed something called rule of capture. This meant that anyone with access to a water source had the right to use as much of it as they could, even to the detriment of the rest of the community. As a result, groundwater pumpers around Fort Stockton caused nearby Comanche Springs to run completely dry:

The lawsuit filed on behalf of Bill Moody’s dad and other farmers on Comanche Creek, Middle Pecos Irrigation District v. Williams, went all the way to the Texas Court of Appeals, which in 1956 affirmed that the downstream farmers had no recourse to keep Williams and his neighbors from pumping the springs dry. The reason why, the court said, was the Rule of Capture, which protects landowners from liability if the use of the groundwater beneath their property dries up their neighbors’ wells or streams.

Only a few years before, the Texas Legislature had passed the Texas Groundwater District Act, which for the first time allowed local governments to voluntarily regulate groundwater. But when the springs began to run dry, no groundwater district had yet been formed in Fort Stockton. In the absence of regulation, the Rule of Capture reigned.

Comanche Springs hasn’t flowed reliably since the 1960s. For a few decades, the old springs would still gurgle awake for a month or two in the winter, when irrigation on the Williams Farms and its neighbors went fallow. Now thanks to rising temperatures and a lengthening growing season, the Williams Farms are able to produce a winter harvest, and the wintertime flows have ceased as well.

First in time, first in right might be causing problems for eastern Idaho farmers, but without it, Thousand Springs might well have dried up decades ago. If Idaho operated according to the rule of capture, then groundwater pumpers in eastern Idaho could legally extract all the water from the ESPA, leaving nothing for the Magic Valley. Clearly, some sort of regulation is necessary here.

Of course, measuring the amount of water in an aquifer is no easy task. Hydrogeologists have tools to do so but it’s not as easy or obvious as seeing the level of a river or how much snow is on Bogus Basin. When the same government that told us to stay home, wear masks, and stay six feet away from other people lest we die of Covid tells us that the aquifer is low so we need to reduce our water usage, it’s natural for many people express skepticism, especially when big corporations with lots of money are in the mix.

But not everything is necessarily a globalist conspiracy to destroy our civilization. Adjudicating the use of a common resource such as water is one of the legitimate purposes of government, and thus far they are doing so according to the law as well as various contracts and court decisions crafted over the decades. Remember that we live in a desert in southern Idaho, and our dairies, potato farms, and endless suburbs are only made possible by tremendous feats of engineering that provide access to life giving water.

As our population grows, so does our need for water. The counties served by ESPA grew from just over 400,000 people in 1999 to nearly 600,000 this year, an increase of nearly 50%. More people and more industry will necessarily draw more water out of the ground. As the lesson of Comanche Springs shows, it is entirely possible that we deplete this essential resource if we are not careful.

Do our regulatory doctrines need updating? Instead of first in time, first in right,should we instead adopt some sort of first in need doctrine? That would potentially allow the government to pick winners and losers, and it’s a certainty that the winners would be those who are the most politically connected — exactly the situation that some worry is already happening with TFCC and Idaho Power. Are there other options that will honor property rights, ensure an equitable distribution of water for everyone who needs it, and maintain our water supply for the future? Should senior water rights holders be forced to adopt measures to ensure more efficient usage?

One other factor I have not yet mentioned is the proposed Lava Ridge Wind Farm. Not only will this project require some water, it will also likely impact the ESPA itself because of the drilling operations necessary to install the massive wind turbines that the project has planned. It seems foolish to throw such an invasive project into an already precarious situation.

With the curtailment order lifted, hopefully eastern Idaho farmers will be able to get the full value for their investments. Making a living as a farmer means very tight margins, where one small variable can mean the difference between failure and success. For the past hundred years or more, the farming industry has been a race toward the next innovation to squeeze just a bit more efficiency out of the process. Farmers need predictability. Without knowing how much water they will have at their disposal, they cannot know how many seeds to buy and how many acres to plant. Since government has the responsibility of regulating water usage, it also has a responsibility to keep farmers informed as to how much water they can expect to use in each coming year.

An officer known as the watermaster is responsible for ensuring that water is provided based on the proper rights. Ronald Carlson served as watermaster for the Snake River region from 1978-2006, and I have used his testimony for background for this article.

The Affidavit Of Ronald Carlson

1.36MB ∙ PDF file

This is an extremely complex issue, one in which I’ve barely scratched the surface here. There are many more factors to consider, and many more perspectives to take in, than I have had the space to lay out. Take some time to watch the videos I’ve linked, read the stories and the applicable sections of the law, and share it with friends and family. (Here is another good resource.) I’m sure this issue will come before the Legislature in 2025, and we as citizens must do our due diligence in keeping our lawmakers informed and accountable.

Water is life, and it falls upon our government to ensure equitable access to that water for all stakeholders. Having learned a lot about this issue over the past few weeks, I will at least take my drinking water a little less for granted.