Battle Over The West Fork Pine Creek

The West Fork Pine Creek Dilemma: A Legal and Environmental Crossroads in Shoshone County, Idaho

By Casey Whalen

Shoshone County, nestled deep in North Idaho’s pristine forestland, is a haven for outdoor enthusiasts and off-road adventurers. Among its rugged terrain lies West Fork Pine Creek, an area of striking natural beauty, braided riverbeds, and historical intrigue. Yet this breathtaking corridor has also become the epicenter of a growing legal and environmental controversy involving motorized access, private property rights, federal land management, and recreation use ethics.

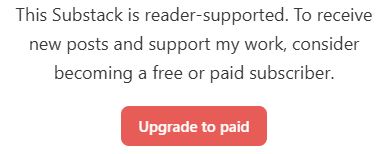

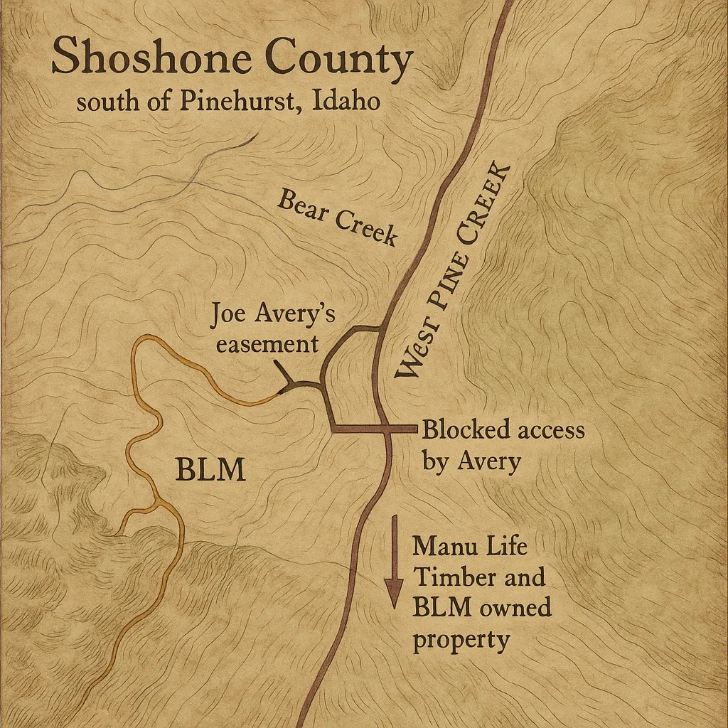

In 2012, the North Idaho Trail Blazers (NITB), an off-road recreation group, approached landowner Joe Avery to seek access through West Fork Pine Creek. Avery permitted use of a non-motorized easement for access to BLM lands, which ultimately led to a rugged trail known as “The Roller Coaster”—a narrow, rocky corridor favored by rock crawlers. This two-mile stretch passes through a patchwork of private land, including holdings by Joe Avery, Manu Life Timber Company, and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

Initially, the impact appeared minimal. But by 2020, Avery noted a sharp uptick in use.

“They traveled in caravans, and the dust, noise, garbage, and bathroom use spilled onto my father’s property.” -Joe Avery

He eventually constructed a physical barrier, blocking vehicle traffic across his land. That action would ignite a broader debate over land rights, environmental protection, and access law.

Legal Framework: Road Status and Validation Efforts

At the heart of the dispute lies a fundamental legal question: Is the road through Avery’s land a public road? If so, does it permit motorized access? The Shoshone County Board of Commissioners (BOCC) was petitioned to validate the route as a public county road—essentially designating it as open for motorized use. However, historical records undercut that claim.

The commissioners examined minutes from a 1909 meeting regarding the establishment of the road. The original petition was rejected, and the county never constructed or maintained a road through West Fork Pine Creek. There was no formal dedication, and no public funds were used to maintain the road. In July 2025, the BOCC formally denied the validation request, stating that insufficient evidence existed to establish West Fork Pine Creek Road as a public highway.

Despite this denial, the BOCC granted non-exclusive public access, clarifying that any further use must comply with private landowner consent and existing travel management policies. This nuanced decision attempted to balance public recreational interests with private property rights, but it satisfied few on either side.

Federal Policy and BLM’s Role

The BLM plays a critical role in this controversy. According to its 2007 Travel Management Plan (TMP), all vehicle travel on BLM-managed lands is restricted to designated motorized routes. The West Fork Pine Creek route, including The Roller Coaster, was not designated for motorized use and is officially managed as a non-motorized corridor.

Moreover, BLM officials confirmed that the structures and trail alterations made by the NITB, including around 60 man-made features such as “kelly humps” and “tank traps,” were unauthorized. The group had been operating under a trail maintenance permit, which did not allow for this level of alteration.

A July 2025 Environmental Assessment by the BLM cited multiple violations of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), significant soil erosion, water pollution, and wildlife disruption. The BLM’s proposed solution—complete removal of the man-made structures and full route restoration—has been met with widespread support from environmental groups, residents, and even the Shoshone County Sheriff.

Environmental and Public Safety Concerns

Environmental organizations like the Friends of the River Coalition have documented extensive harm caused by unauthorized rock crawling. Their findings include creekbed destruction, displaced wetland species, and trash accumulation. The Idaho Conservation League and Project Restoration have echoed these concerns, citing NEPA violations and advocating for strict enforcement and ecological restoration.

In addition to ecological damage, public safety has become a pressing issue. Sheriff Holly Lindsay noted the substantial strain placed on first responders by the remote and treacherous conditions of the Roller Coaster. Delayed rescues, lack of cell service, and hazardous terrain create unacceptable risks for both users and emergency personnel.

Social Tensions and Community Response

Social media exchanges among off-roaders show intense backlash against the gate Avery installed. Some commenters have joked—or outright encouraged—destroying the barricade. These tensions have been exacerbated by misinformation about land ownership and the route’s legal status.

For Avery and others, this isn’t simply a fight about access—it’s about stewardship. In an April 2023 letter to the BLM, Avery questioned whether the NITB had obtained proper permits for their large-scale “Cabin Fever Run” and raised concerns about illegal off-route driving through wetlands.

Conclusion: The Path Forward

The West Fork Pine Creek dilemma highlights a broader national struggle: how to balance outdoor recreation, private property, environmental protection, and public access. As of July 2025, the BLM’s final recommendation is clear: remove all unauthorized structures, restore the route to its original condition, and uphold NEPA processes moving forward.

Shoshone County’s decision not to validate the road as public aligns with historical documentation and legal precedent. Yet the issue is far from settled. The fate of West Fork Pine Creek now hinges on enforcement, restoration efforts, and the community’s willingness to engage in lawful, respectful recreation. Whether viewed as a legal dispute, a conservation challenge, or a cultural clash, it stands as a powerful case study in the complexities of managing public lands in the American West.

On August 5, 2025, Paul Loutzenhiser met with the Shoshone County Commissioners today to help them understand why they should make the lower road (West Fork Pine Creek) public, but most of his dissertation was related to the part of the road on federal land, which the county has zero jurisdiction.

The road validation case from its inception has just been about two parcels between the actual road and the closed-to-motorized BLM-managed land.

The county would have needed to inform the U.S. government about their road creation before it was “reserved” as a national forest in 1906. The “designation” in 1909 was too late. They would have had to ask the federal government for permission to use it. That process mandated a survey of that which they wanted to use. Then they might get an agreement to maintain the road etc.

Which was not done, and not a possible RS2477.

Both their Trail Maintenance & Special Recreation Permits were revoked, so they’d have to re-apply for the TMP to do any work & use NEPA to get their SRP reinstated.

Paul was very weak on why the two parcels (Joe Avery & Manu Life Lumber) should be declared public.

Many locals showed up to oppose this measure by those not from the county, who wish to make Shoshone their playground at tax payers expense.

Update August 24, 2025:

Gate Breach at West Fork Pine Creek – Shoshone County

On Sunday, August 24, a group of five to six Jeeps — led by Paul Loutzenhiser of the North Idaho Trailblazers (NITB) — cut through the gate at the West Fork Pine Creek access point. Eyewitness Joe Avery, who owns nearby land, reported seeing Loutzenhiser personally cutting the gate after the group drove across property of Manu Life Timber land and BLM territory.

The North Idaho Trailblazers claim that AG Raul Labrador essentially gave the okay for this to occur.

The gate, installed by Manu Life Timber, had restricted motorized access in an area officially marked non-motorized use. Cell phone photos captured the incident, which also involved sawing through logs and traveling across roughly two miles of BLM land.

According to Avery, a sheriff’s deputy responded but said enforcement is complicated since the road status is disputed and no official survey defines the county’s jurisdiction.

Loutzenhiser, who owns Boller’s Automotive in Coeur d’Alene, has been a vocal advocate for reopening motorized access to the area, citing what he and others see as unjust land closures.

It is yet unknown, if those responsible will be charged with trespass and vandalism.

Help me continue assisting locals in the great State of Idaho. Please subscribe or send a gift to Venmo / CashApp – NorthIdahoExposed.

Purchase high-quality soap from North Idaho Tallow, using this affiliate link: https://idahotallow.com/?ref=CASEYWHALEN