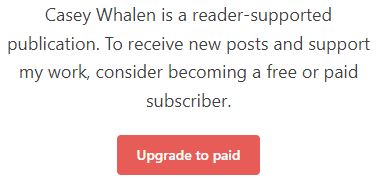

Ben Garrison vs The Troll Army

Censorship and lies helped mold one of the country’s most famous artists, into an Army of One.

By Casey Whalen

For over a decade, political cartoonist Ben Garrison has operated at the intersection of internet culture, free-speech debates, and the fierce polarization of American public life. His drawings, often harsh critiques of government, big money and entrenched interests, have drawn both ardent followers and sharp critics. Along the way, his career has been deeply shaped — and disrupted — by the internet itself: through trolls who altered his cartoons to add offensive content, and through conflicts with organizations like the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) that spotlighted his work amid broader debates over hate speech, censorship and public discourse.

Early Life and Artistry

Ben Garrison grew up in a household that valued independence and self-reliance (as documented in this long form interview). As a child, he was drawn to visual art, spending hours sketching and refining his technique. He pursued art academically and later worked in commercial illustration and newspaper cartoons. But it wasn’t until after the 2008 financial crisis that he shifted his focus toward political cartoons — a medium he saw as a way to critique what he viewed as entrenched power and corruption in the federal government and financial sector.

Garrison’s early political work was shaped by libertarian ideas and a distrust of expansive government power. His cartoons took aim at Wall Street, central banking, and expansion of federal authority — themes that would remain central throughout his career.

Internet Fame — and Infamy

In the early 2010s, Garrison’s work began circulating more widely online. At first, he appreciated the broad reach social media offered. But he soon encountered an unexpected and corrosive phenomenon: a persistent campaign by internet trolls to deface and repurpose his cartoons in hateful and offensive ways.

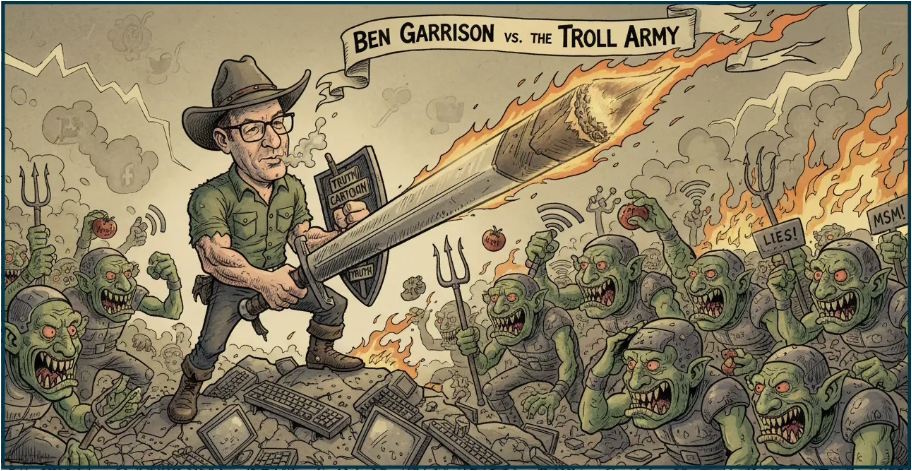

Slide courtesy of OHPI

According to reporting and accounts from Garrison himself, these edits often kept his signature but added racially charged or anti-Semitic imagery that he did not draw, and that conflicted with his stated intent. The alterations spread widely across image boards and social platforms, sometimes reaching larger audiences than his original work. One overview of the situation described trolls on forums like 4chan editing his cartoons into extremist content, keeping his name attached and displacing the originals in search results and social feeds.

Lunch with Ben Garrison at the Dusty Star Saloon in Kalispell, Montana on May 25, 2023 (paid for by the ADL). Photo Casey Whalen

Lunch with Ben Garrison at the Dusty Star Saloon in Kalispell, Montana on May 25, 2023 (paid for by the ADL). Photo Casey Whalen

“That was one of the most frustrating things I’ve ever dealt with,”

Garrison told interviewers in previous public Q&A sessions:

“Someone would take a cartoon that was critiquing central banking or cronyism, edit in a grotesque hateful image, and redistribute it with my signature. And then people would believe I drew it.”

The internet campaign was more than a nuisance; it had professional consequences. Gallery owners, potential clients and online readers often encountered the altered versions first, leading to damaged reputation and lost opportunities. A gallery that once showed his work reportedly severed ties after seeing edited images online.

The specific nature of the alterations varied. Some edits included overtly racist caricatures juxtaposed with Garrison’s compositions; others added conspiracy-laden text or iconography that fed extremist fringe narratives. Troll communities often shared these fake comics as humor or provocation, amplifying the false association.

While Garrison repeatedly denounced these versions, stating they were not his art and did not represent his views, the edits became part of the public mythos about him. One well-known result was the spread of “Zyklon Ben,” a nickname given by some internet users that invoked deeply offensive Nazi references — a stark contrast to the cartoonist’s own stated political positions.

“I never drew a Nazi cartoon,” Garrison has said in earlier interviews, referring to his frustration with misattributed works. “But when you search my name, so often the top results are people accusing me of racism because they saw the doctored stuff.”

The 2017 Cartoon Controversy and the ADL

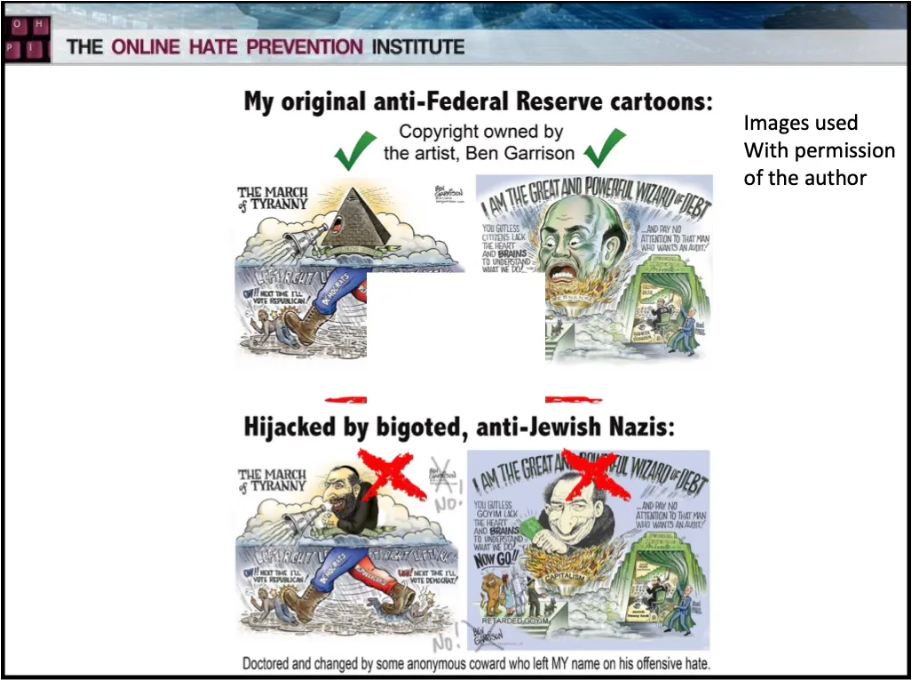

A flashpoint in Garrison’s public profile came with a 2017 drawing commissioned by conservative commentator Mike Cernovich. The cartoon depicted a network of influence linking wealthy financier George Soros and other political actors. Critics, including the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), characterized the imagery as evoking anti-Semitic tropes. The ADL described the cartoon as “blatantly anti-Semitic,” asserting that it played into historic stereotypes about Jewish control and influence.

Garrison defended the cartoon, saying it illustrated his critique of perceived influence in politics rather than targeting any religious or ethnic group. He also pointed out that some references to Jewish banking families in the image were historical critiques of financial power, he said, not expressions of hatred.

In 2019, Garrison was invited to a White House Social Media Summit aimed at discussing perceived bias in technology platforms — but the invitation was rescinded shortly afterward in response to complaints including from the ADL about his cartoon content. Garrison characterized this as a form of censorship and a misunderstanding rooted in misinterpretation of his art.

In 2020, he filed a defamation lawsuit against the ADL, seeking substantial damages, alleging that by associating his work with anti-Semitism the organization had harmed his reputation and professional prospects. His complaint cited emotional distress and loss of business as consequences of the ADL’s public statements.

While public court records indicate that the lawsuit was ultimately dismissed on procedural grounds in 2021 (such as lack of jurisdiction and improper venue), Garrison has described the matter differently in interviews and personal statements. He has said that the dispute was settled in a way that resulted in the contested ADL content being removed or corrected, and that he regarded this as a victory for his reputation. In the public rewrite below, that description is attributed to his own account.

This framing — noting that it reflects his claim and interpretation of events — preserves both factual context and Garrison’s perspective for publication, while not presenting an unverified legal settlement as an undisputed fact.

Even apart from the ADL conflict, the sustained online harassment by trolls took a cumulative toll. Garrison has spoken candidly about the effect of seeing false, offensive material associated with his name, and how it made it difficult to pursue commercial art outside of political cartoons.

“People made entire blogs and image galleries devoted to portraying me as something I’m not,” he told interviewers. “It’s haunted me for years, and financially it nearly destroyed my ability to do fine art.”

His wife, Tina, became crucial in this period — handling his social media presence and helping him reclaim his voice and audience online after the flood of doctored content. Together they navigated the tricky landscape of online platforms, trolls, and the increasingly charged culture of political commentary on social media.

Garrison’s original cartoons cover a wide range of topics — from critiques of economic policy to skepticism about government institutions. Some of his work resonates with a conservative base and has found an audience on platforms that champion anti-establishment voices.

Critics, however, argue that even his original cartoons sometimes echo themes that dovetail with fringe or conspiratorial thinking, particularly when they reference global influence or central banking conspiracies. Responsible publication typically contextualizes such critiques by noting both the artist’s intentions and how different audiences interpret these themes. Highlighting where edits and misuse of art have misled audiences adds necessary nuance to understanding the broader impact of his work and public reception.

Garrison’s story sits within a larger cultural conversation about free expression online, platform moderation and the responsibility of creators and organizations in addressing offensive content. His experiences raise questions about how easily reputations can be shaped by altered content, and how public institutions respond when art intersects with charged social issues.

For readers unfamiliar with the dynamics of internet culture, the idea that a piece of visual satire can be altered and re-circulated with new meaning — and significant reputational consequences — might seem surprising. But in the age of memes and rapid, decentralized sharing, such transformations are common, and they underscore how challenging it can be to maintain control over one’s work once it enters the public domain.

Today, Garrison continues to produce cartoons and engage with his audience, increasingly focused on direct distribution through his own channels rather than traditional galleries or third-party platforms. He speaks of maintaining his creative voice and addressing what he sees as mischaracterizations of his work and intentions.

Whether one agrees with his political stance, his art style, or his interpretations of events, his story illustrates a modern dilemma: how creators navigate a digital ecosystem where original work can be widely repurposed, misinterpreted, and weaponized — and where debates about intent, impact, and interpretation continue to evolve.

See my interview with Mr. Garrison at the Red Pill Expo in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, in 2021.

Mr. Garrison spoke at the Red Pill Festival (no association with the Red Pill Expo), an event in St. Regis, Montana, July 24, 2022.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

If you enjoy Casey Whalen, share it with your friends and earn rewards when they subscribe.