The Many Lies of Bob Woodward

By Roger Stone

Bob Woodward lied about Nixon, Watergate, the war in Iraq, Iran-Contra and the late comedian John Belushi. Why should we believe his latest lies about President Donald Trump?

Fabled former Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward now says that former President Donald Trump has spoken to Russian leader Vladimir Putin multiple times since leaving the Presidency and that Trump even sent Putin a Covid-19 test, all stoutly denied by the Kremlin and the former president.

Well, Bob, just as people who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones, “journalists” whose careers are predicated on lies shouldn’t taunt public figures, because some public figures aren’t afraid to upend the apple cart. Bob Woodward needs a lot more scrutiny; his career is based on a series of lies, about Watergate, about Iran-Contra and about the Iraq War and even about the late comic genius John Belushi.

Bob Woodward has an epic career of lies: If he were Pinocchio, his nose would rival the length of the Washington Monument. Woodward’s initial reporting on Watergate and his subsequent books on the subject are a mosaic of fabrications that have been largely unchecked by the media, because to question Woodward and Watergate would be to question the state of American journalism. Watergate also ushered the Washington Post into the Ivy League of newspapers, so the Washington Post has been left with the onerous responsibility of protecting Woodward and his lies.

Mark Felt in the guise of “Deep Throat” has also played a critical role in Woodward’s Watergate fabrications. Though Mark Felt was probably a source for Bob Woodward, the most damaging of the Deep Throat revelations were most likely spilled by Alexander Haig, Woodward’s former White House colleague. The media sanctioned/ WaPo created Watergate narrative completely ignores the fact that Woodward was a naval intelligence officer who briefed Alexander Haig at the White House in 1969 and 1970, when Haig was Kissinger’s assistant at the National Security Council.

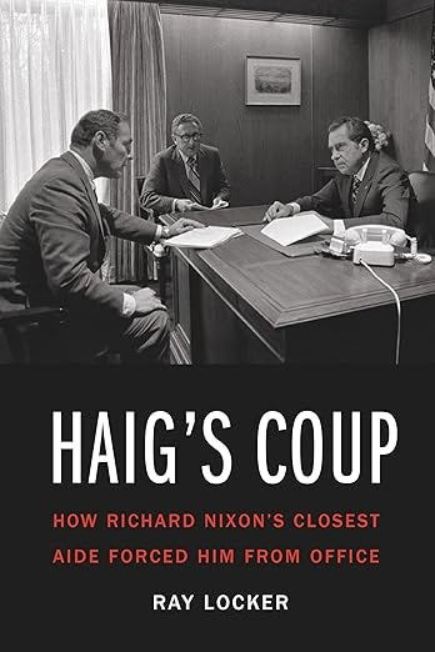

Woodward’s big lie is that he didn’t meet Alexander Haig until 1973 despite the Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman under Nixon and Nixon’s Secretary of Defense confirming that Woodward started briefing Haig at the White House in 1969. If Woodward’s big lie about Haig had been exposed, then the synergistic myths of Bob Woodward and “Deep Throat” would have been shattered and swept away by tempests of truth. USA Today reporter Ray Locker destroyed the myth of Felt being Deepthroat in his widely overlooked book Haig’s Coup.

Woodward is a carefully crafted myth, and the myth has been fashioned since his days in high school. However, the authors of Silent Coup, a more accurate history of Watergate, written by Len Colodny and Robert Gettlin, conducted several interviews regarding Woodward that severed the man from the myth. Silent Coup dissects Woodward’s formative years in which he’s portrayed himself as a high school introvert and ham radio geek. But, in reality, Woodward was quite popular in high school. He was elected to the student council in each of his high school years. He was even chosen to give his class’ commencement speech, which was gleaned from The Conscience of a Conservative, a book written by ultra conservative Barry Goldwater.

After Woodward graduated from high school in Wheaton, Illinois, he glided into Yale on a Navy ROTC scholarship. He was even recruited for Book and Snake, one of Yale’s secret societies. The Silent Coup authors unearth a couple of interviews Woodward granted, after his Watergate celebrity, about his years at Yale. In one interview, he discussed his disenchantment with the Vietnam War and seeking sanctuary in Canada. Woodward’s recollections about his collegiate misgivings on Vietnam diverge from the memories of his high school sweetheart and first wife, who visited him at Yale. The Silent Coup authors interviewed her, and she disclosed that Woodward’s warmongering views on Vietnam were unabated when he attended Yale. When she was asked if Woodward ever talked about seeking sanctuary in Canada from his ROTC commitment to the Navy, she responded with a resounding, “Heavens no.”

Following Woodward’s graduation from Yale, his ROTC scholarship mandated a six-year hitch in the Navy—four years of active duty and two years in the naval reserves. Woodward has depicted his naval experience as “miserable,” even though his first commission landed him on the USS Wright, which was a coveted assignment by naval personnel. The USS Wright was an aircraft carrier that had been transformed into a high seas, high-tech command post. The ship’s state-of-the-art communications received top-secret communiqués that also streamed into the White House, and Woodward was conferred a top-secret crypto clearance. Following Woodward’s tenure on the USS Wright, he was assigned to the USS Fox.

After Woodward had been in the Navy for four years, he was assigned to the Pentagon, and he served a fifth year of active duty. While Woodward was at the Pentagon, he manned a secret communications station that relayed secret communiqués for President Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger, Nixon’s National Security Advisor, and his responsibilities included briefing Alexander Haig, Kissinger’s military assistant at the National Security Council.

The Nixon administration deployed the Navy’s secret communications center that Woodward manned to circumvent customary diplomatic channels, because Nixon wanted the military and CIA hawks to be cut out of the loop while he and Kissinger were forging diplomatic relations with China and conducting Strategic Arms Limitation Talks with the U.S.S.R. Nixon had previously issued National Security Decision Memoranda 2, which elbowed out the State Department, Department of Defense, and the CIA from Nixon’s major geopolitical moves.

Joint Chiefs Chairman Admiral Thomas Moorer was a fervent anti-communist, and he was particularly piqued by Nixon’s double-dealing with Russia and China, so Moorer ultimately initiated an espionage campaign that was focused on Nixon and Kissinger’s clandestine negotiations with China and Russia. Haig was the inside man for the Joint Chiefs. He ensured that Navy Yeoman Charles Radford, a stenographer in the Joint Chiefs liaison office to the National Security Council, was in the right place at the right time to pilfer top-secret documents from the National Security Council. One of Nixon’s overriding concerns was forging diplomatic relations with China, and he covertly backed Pakistan in its 1971 war against India, because Nixon wasn’t pleased with India when it signed a friendship pact with the USSR, and he also befriended Pakistan since Pakistan was an ally of China.

Nixon’s hijinks with India and Pakistan was leaked to columnist Jack Anderson, and he crafted a Pulitzer Prize winning scoop that enraged Nixon. The Nixon administration thought Radford had been Anderson’s source, because both were Mormons and socially acquainted, and Nixon administration investigators polygraphed Radford. Though he wasn’t the source for Anderson’s scoop, he spilled the secrets about the Joint Chiefs espionage against Nixon.

After Nixon was briefed on Radford’s revelations, he met with Attorney General John Mitchell to deliberate Radford’s confessions. Nixon was fuming over the Joint Chief’s duplicity, but Mitchell insisted that Nixon bury the matter, offering a number of rationales, and Nixon grudgingly concurred with Mitchell. A primary reason to bury the Joint Chiefs’ espionage was that Moorer was aware of Nixon’s backchannel communications with China, and a public airing of the matter might publicize and jeopardize his negotiations with China. Legislative hearings on Moorer and Radford would also undercut public opinion of the military and also military morale, which were rock bottom due to the Vietnam debacle. So Nixon, ever the student of realpolitik, decided to crush Moorer’s power. Nixon ultimately retained a neutered Moorer as the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, and he had Welander and Radford exiled to distant assignments.

Although a White House investigation into the Joints Chief espionage implicated Haig, Nixon’s burying of the matter put the kibosh on the investigation, and it was never brought to Nixon’s attention that Haig had been part and parcel of the espionage ring. So, remarkably, Haig wasn’t tainted by the affair, and Nixon’s expeditious resolution to bury the matter essentially sparked a fuse that would ultimately detonate his presidency.

Woodward had left the Navy shortly before Radford started pilfering Nixon and Kissinger’s secrets, but Woodward briefed Joints Chiefs Chairman Moorer and Haig, and he also served under Admiral Robert Welander earlier in his career. So Woodward was well acquainted with Moorer, Haig, and Welander—the primary ringleaders of the espionage ring. After Woodward left the Navy, he inexplicably avoided serving in the naval reserves and embarked on his civilian incarnation, which were a series of extremely outlandish vocational decisions.

Woodward was accepted to Harvard Law School, but he inexplicably relinquished his legal aspirations and ostensibly worked out a very unconventional arrangement with the Washington Post: Woodward, who had no newspaper experience, would work at the Post for two weeks without pay, and if the newspaper felt that he had the talents on par with the Washington Post, the newspaper would hire him. A retired Washington Post editor commented on Woodward’s initial employment at the Washington Post: “Bob had come to us on very high recommendations from someone in the White House. He had been an intelligence officer in the Navy and had served in the Pentagon. He had not been exposed to any newspaper.”

Woodward, however, had significant troubles producing intelligible copy, and, after two weeks, the Washington Post dismissed him. Although the account of Woodward’s brief tenure at the Post seems mired in improbability, his next professional move is also mired in improbability, because he continued to forgo Harvard Law School and landed a job as a reporter at the Montgomery County Sentinel, a weekly in suburban Maryland, which is relative destitution when compared to the earning potential of a Harvard Law School graduate.

Woodward was at the Sentinel for nearly a year when the Washington Post then hired him as a full-time staff reporter. Woodward had been at the Washington Post for nine months when the Watergate burglary occurred on June 17, 1972. With the exception of G. Gordon Liddy, all of the burglars had CIA affiliations. Howard Hunt and James McCord had been CIA agents, but they had ostensibly retired from the agency. Former Harper’s Magazine Washington, DC correspondent Jim Hougan’s meticulously researched book Secret Agenda about Watergate demonstrates that Hunt and McCord were still working for the CIA, and they sabotaged the burglaries to ensure their ultimate arrest at the Watergate. McCord even wrote a letter to the judge overseeing the case stating that the burglars had committed perjury, and they had been pressured to maintain their silence. The trap had been set.

Following the burglars arrest at the Democratic National Committee, the Washington Post appointed nine reporters to the story, and one just happened to be Bob Woodward, who penned the Washington Post’s first major revelation on Watergate. Woodward linked the Watergate burglars to Howard Hunt, who worked at the White House following his “retirement” from the CIA.

Deep Throat, Woodward’s “executive branch” source, said that the FBI deemed Hunt to be a person of interest in the Watergate break-in, and Woodward would be accurate if he reported Hunt’s link to the burglars and also to the White House (Woodward didn’t contrive the name of Deep Throat for his “executive branch” source during his Washington Post Watergate reportage—he coined to the term Deep Throat after Nixon had been vanquished and when he and Bernstein wrote All the President’s Men). The Washington Post published Woodward’s article on Hunt three days after the Watergate burglars’ arrest. Woodward’s article was the Post’s first Watergate scoop, and the Woodward myth was thus launched.

Woodward and Bernstein quickly started mass-producing articles about Watergate that ushered the scandal into the national consciousness. So, in February of 1973, the U.S. Senate voted 77 to 0 to form the “Watergate Committee” to investigate the Watergate burglary. The Watergate Committee attempted to hire Woodward as a committee investigator due to the scoops he was churning out about Watergate, but Woodward rejected the Watergate Committee’s offer. However, he recommended a childhood friend, Scott Armstrong, and the Committee conscripted Armstrong to be one of its investigators. Armstrong, of course leaked to Woodward.

The Watergate Committee’s senior Republican Senator, Howard Baker, was leery of Woodward’s scoops, and he had a hunch that Woodward was affiliated with the CIA. Baker directed one of the Committee’s counsels to ask the CIA if Woodward was in its employment, but the CIA rebuffed the request. A memo by a Nixon adviser recounts the CIA’s rebuff of Senator Baker’s request, so Baker dispatched the counsel’s request and a letter to CIA Director William Colby, inquiring about Woodward’s relationship to the CIA. According to the memo, a “few hours” after Baker dispatched the letter to Colby, the senator was the recipient of a phone call from an “incensed” Bob Woodward. Woodward’s phone call to Baker demonstrates that he had a snug relationship with the CIA director.

As the Watergate Committee and Washington Post scrutinized Watergate, Nixon’s inner circle became tainted by the cover-up, and they started tendering their resignation letters. So in May of 1973 Nixon appointed a seeming sycophant—Alexander Haig—to be his new chief-of-staff. since Nixon had quashed the Joint Chiefs’ espionage investigation so quickly, he was oblivious to Haig’s role in the espionage ring.

Nixon felt that Haig was a devoted and trustworthy sycophant, but Haig had unbridled disdain for Nixon due to Haig’s conviction that Nixon snatched defeat from the jaws of victory in Vietnam by his massive troop withdrawals. Haig also didn’t trust China and Russia, and he was appalled by Nixon’s friendly overtures to both countries. Woodward and Bernstein’s The Final Days discusses Haig’s disdain for Nixon when commenting on Nixon’s close friendship with a Florida VIP, who had connections to underworld: “Haig sometimes referred to the President as an inherently weak man who lacked guts. He joked that Nixon and Bebe Rebozo had a homosexual relationship, imitating what he called the President’s limp wrist manner.”

Also in May of 1973, the U.S. Senate’s Watergate Committee started to televise its hearings and Archibald Cox was chosen to be the special prosecutor of a grand jury charged to investigate possible criminal improprieties that were associated with the Watergate break-in. The first of the president’s men who opted to cooperate with the Watergate Committee and finger Nixon in the Watergate cover-up was White House Counsel John Dean—he also fingered Attorney General John Mitchell in the Watergate break in. But Silent Coup shows that Dean played a major role in initiating the Watergate burglary without the knowledge of Nixon or Mitchell, and his testimony before the Watergate Committee is riddled with lies. Although Dean was an accomplished liar, the Watergate Committee and the grand jury didn’t have incontrovertible proof of Nixon’s collusion in the Watergate cover-up, because it was Dean’s word against Nixon’s word.

The potentially incontrovertible proof of Nixon’s collusion in the Watergate cover up ultimately came from Alexander Butterfield, who revealed to the Watergate Committee that Nixon had a clandestine taping system that recorded his oval office conversations. Butterfield had left the Nixon administration in 1972, but, before his departure, he had been an aide to Nixon’s former chief-of-staff, H.R. Haldeman, and oversaw Nixon’s oval office taping system. Butterfield’s revelations to the Watergate Committee were a bombshell. If Butterfield had not exposed the taping system, Nixon would have walked away from Watergate with his presidency intact—albeit a little battered.

In my book, Nixon’s Secrets: The Rise, Fall, and Untold Truth about the President, Watergate, and the Pardon, I discuss Butterfield being a CIA plant who managed to infiltrate the White House. Butterfield has said that H.R. Haldeman approached him about a White House position in the Nixon White House, but, according to Haldeman, Butterfield is lying, because it was Butterfield who approached Haldeman.

Woodward contends in All the President’s Men and in his latest opus of lies about Butterfield, The Last of the President’s Men, that Mark Felt had dropped Butterfield’s name to him. Instead of digging into Butterfield like a bona fide investigative journalist, Woodward made the very bizarre move of proffering Butterfield’s name as a person of interest to the Watergate Committee via his close friend and Committee investigator Scott Armstrong. It should be noted that there’s an interesting chronological correlation between the first time Woodward proffered Butterfield’s name to the Committee and Haig becoming Nixon’s chief-of-staff: Woodward initially proffered Butterfield’s name to the Committee in May of 1973—shortly after Haig was appointed Nixon’s chief-of-staff. Nixon’s taping system was a safeguarded secret that was known to a select few in his inner circle, and Haig was made privy to the taping system only when he assumed the mantle of Nixon’s chief-of-staff. At the time, even Kissinger wasn’t privy to the taping system. Accordingly, it’s extremely doubtful, if not utterly impossible, that Mark Felt would’ve been privy to the taping system.

When Woodward first disclosed Butterfield’s name to the Committee, via Armstrong, the Committee didn’t act on the tip, because Butterfield had held a relatively lowly position on the White House staff and the Committee didn’t see his significance. But Woodward didn’t give up, and he approached the Armstrong again, proffering Butterfield’s name. On Friday July 13, 1973, Armstrong finally questioned Butterfield, and Butterfield unfurled the existence of the oval office taping system. The Committee hastily scheduled Butterfield to testify the following Monday. Nixon’s doom was on the precipice of being sealed—unless he received an executive injunction against Butterfield testifying before the Watergate Committee.

Woodward maintains in All the President’s Men that he was edified about the oval office taping system the day after Armstrong interviewed Butterfield, even though he had previously approached the Watergate Committee twice about Butterfield. According to All the President’s Men, Woodward phoned the editor of the Washington Post, Ben Bradlee, that Saturday night and told him of the combustible scoop. But Bradlee reportedly told Woodward that his information was a “B plus” story, and he opted to sit on the information instead of publishing an article on it the following day—Sunday. Bradlee consigning Woodward’s information on Butterfield to a “B plus” story is rather mystifying, because Butterfield was slated to testify about the oval office taping system in two days, which had the potential to sink the Nixon Administration.

A foremost rationale that can be offered for Bradlee’s irrational decision is that if a story regarding Butterfield’s impending testimony about the clandestine taping system were published on Sunday, Nixon would be cognizant of Butterfield’s upcoming testimony slated for the following day, and he would have time to seek an executive privilege injunction to bar Butterfield from testifying before the Watergate Committee.

Although it’s possible that Haig was privy to Butterfield’s upcoming testimony on Saturday, he was definitely privy to it on Sunday due to the fact that he and Nixon’s special counsel Fred Buzhardt conversed about it. Nixon’s Special Counsel said that Nixon was hospitalized for pneumonia that weekend, and Haig opted not to distract him about the Butterfield testimony. Nixon was indeed hospitalized for pneumonia that weekend, but he was quite cogent as evinced by a series of protracted phone conversations he had from his hospital bed, and he was released from the hospital the following day.

Haig ultimately told Nixon about Butterfield’s appearance before the Watergate Committee on Monday morning. But, at that point, Nixon didn’t have the time to seek an injunction barring Butterfield’s testimony. Nixon wrote in his memoirs that he was absolutely “shocked” to hear about Butterfield’s testimony, because he thought the existence of the oval office taping system would never be exposed.

Butterfield’s revelations about the oval office taping system before the Watergate Committee provoked the Watergate grand jury special prosecutor to subpoena recordings of oval office conversations that might incriminate Nixon in the cover-up of Watergate. A hearing was called that pitted the grand jury’s special prosecutor against Nixon’s attorneys—Nixon’s attorneys contended that the tapes were protected by executive privilege. The judge in the case, John Sirica, ruled that Nixon had to relinquish the tapes. This, of course sealed Nixon’s fate.

According to All the President’s Men, Deep Throat enlightened Woodward about a gap in the tapes in the first week of November, and the following week Woodward and Bernstein penned a front-page article for the Washington Post that discussed the tapes’ “suspicious” gaps. Woodward wrote that he set up his meetings with Deep Throat (AKA, Mark Felt) by repositioning a flowerpot that was on the balcony of his apartment. But Woodward’s tale of him setting up a meeting with Felt in early November via the flower pot, when Felt disclosed the “suspicious” erasure, is an obvious lie. Felt had retired from the FBI approximately six months before their purported meeting in early November, and he was living in Virginia.

Consequently, if Woodward’s tale of rendezvousing with Felt in early November is veritable, it means that Felt would have made regular jaunts from Virginia to Washington, D.C. for six months following his retirement to scrutinize Woodward’s balcony. Moreover, at the time, Woodward was living at an apartment on P Street whose balcony didn’t face the street, but, rather, the interior of a courtyard. So even if Felt is making repeated drives into D.C., and parking his car to scrutinize Woodward’s balcony, it’s almost impossible for him to be in the know about the “suspicious” erasures in early November, because only a select few at the White House were aware of the error committed by Nixon’s secretary. Such a development is highly improbable compared to Haig simply relaying to his former briefer, Bob Woodward, that the tapes contained suspicious and deliberate erasures. Finally, Woodward’s big lie that he didn’t meet Haig until 1973 is an additional indication that Haig transmitted the information about the tape erasure to Woodward.

Although playing an instrumental role in the demise of Nixon’s presidency made Woodward a darling of the left, he has nonetheless been an exceptional cheerleader for the hawks and neocons. For starters, his books on the Bush administrations wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Plan of Attack and Bush at War, are apologist palavers that vindicate the neocons disastrous and ill-fated policies and also attempt to give their lies about weapons of mass destruction a garish spin of veracity.

In addition to the tomes Woodward has written to vindicate Bush’s wars and the lies that led to war, he gave America a glimpse of his true colors during the Valerie Plame affair, which entailed members of the Bush administration illegally outing Valerie Plame as a CIA agent in retribution for her husband’s, Joseph Wilson, very vociferous stance that Niger didn’t furnish Saddam Hussein with yellowcake uranium. After prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald slapped Scooter Libby, Vice President Cheney’s former chief of staff, with perjury for lying about his role in illegally outing Valerie Plame as a CIA agent, he received a call from a “White House official” who told him that Woodward was, in fact, the first reporter that the Bush administration had made privy to Plame’s identity as a CIA agent. The unknown White House official relayed to Fitzgerald that Woodward was apprised of Plame’s identity a week before Libby outed Plame to the Judith Miller, the New York Times’ primary cheerleader for Bush’s Iraq War.

It’s been speculated that Cheney may very well have leaked Plame’s CIA status to Woodward, because the week that Woodward was reportedly edified about Plame, Cheney’s office was a hornets’ nest of activity in its quest to exact retribution against Joseph Wilson, and Woodward also interviewed Cheney for his book State of Denial that week. In a court filing, Fitzgerald implicated Cheney in the leak and the cover up. “When the investigation began, Mr. Libby kept the vice president apprised of his shifting accounts of how he claimed to have learned about Ms. Wilson’s CIA employment.” However, both Woodward and Cheney are chronic liars, so we may never know if Cheney blew Plame’s cover to Woodward.

After Fitzgerald received the tip about Woodward being the Bush administration’s first recipient of Plame’s leaked CIA status, Fitzgerald deposed Woodward. Although members of the Bush administration had committed a serious felony when they outed Plame as a CIA agent, Woodward had belittled the whole affair. On the night before Libby’s indictments were announced, Woodward made an appearance on the Larry King Show, and he referred to the Plame affair as “laughable” and “quite minimal.” And he had previously called Fitzgerald a “junk yard dog prosecutor.”

Woodward’s account of his deposition to Fitzgerald, which was vetted by former Washington Post editor-in-chief and CIA apparatchik Ben Bradlee, stated that he had informed his Post colleague Walter Pincus of Plame’s CIA status in June of 2003, the same month he had been the recipient of the leak. But Pincus testified under oath that a White House official revealed Plame’s status to him much later, and Pincus was adamant that he had not learned of Plame’s CIA status from Woodward, because Woodward had potentially left him susceptible to a perjury indictment.

As usual, Woodward skated from his alleged lie to Fitzgerald. Moreover, Woodward and the New York Times’ Judith Miller were two of the Bush administration’s primary cheerleaders for Saddam’s nonexistent weapons of mass destruction to the left. When that mendacity was exposed, the New York Times canned Judith Miller, but Woodward was unscathed—as usual. In fact, a number of Woodward’s lies have been exposed over the years, but he’s the Teflon reporter, because Woodward has to be protected at all costs. To expose Woodward would be to expose our current state of lapdog media and also the epic deceit of the Washington Post.

In 1987, Woodward claimed to speak to former Director of the CIA William Casey before his death for his book, Veil: The Secret Wars of the CIA. “Indeed, Woodward did try to enter the hospital room, but was interdicted by the agent in the hot seat [outside Casey’s door] and gracefully shown to the exit,” said Kevin Shipp, a former CIA agent on security detail outside of Casey’s hospital room. “We, myself included, were there 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” Shipp wrote. “All of us were under orders to let no one into the room.”

Shipp added that had Woodward impossibly made his way into the hospital room he could not have gotten an interview. The brain tumor Casey was suffering from had rendered him incapable of speech. Casey’s wife widow Sophia backed Shipp’s claim and added she had seen CIA records and that “Bob Woodward got in and was caught by security and thrown out,” before entering Casey’s room.

Yet, Woodward said he had gained access to the room, and he had spoken to Casey. Woodward also claimed that, incredibly, Casey chose Woodward as the recipient of a deathbed confession. According to Woodward Casey reportedly acknowledged to the reporter that he knew about an illegal diversion of funds by the Reagan Administration from Iranian arms sales to Contra rebels attempting to overthrow the Nicaraguan government.

When President Ronald Reagan, saw the fabrication in Woodward’s book and a “60 Minutes” interview coupled with Woodward’s assertion that Casey believed the President was a “strange” man, who was “lazy and distracted,” he was appropriately angry. “He’s a liar & he lied about what Casey is supposed to have thought of me,” Reagan wrote in his diary. William Casey’s widow said that it was all a Woodward-created untruth. “Bill would never say that about the President,” Sophia Casey said. “Bill loved Reagan and they were very close. It’s been very hurtful. It is terrible for the family. You can imagine how Reagan feels.”

Woodward also lied in his controversial biography of the late comic genius John Belushi. Rolling Stone laid this out on September 27, 1984.

“It all started in May. Wired: The Short Life & Fast Times of John Belushi, by Bob Woodward, was officially published on June 4th, 1984, two years after the comedian died of an overdose of cocaine and heroin. Judy Jacklin Belushi, and the friends who circle around her like satellites, had received advance copies of the book, and the entire situation was a mess from the start. There had been such a sense of expectation about — not only had John Belushi’s widow initiated the project, but she had also read her diaries to Woodward and persuaded her friends to talk— even the famous ones, like Dan Aykroyd and John Landis. She had, above all else, hoped for a sympathetic biography. Instead, she got 432 pages of cold facts, the majority of them drug related and ugly. “The man in Wired is not the man I knew,” Jacklin said. And with that began the controversy.

She had already had misgivings. “There were innumerable problems with Bob getting the manuscript to me,” Jacklin said later. “It was, ‘Oh, your sister is supposed to send you a copy…. No, it was Federal Expressed to you.’ That went on for two weeks.” Yet when she finally did receive Wired, she didn’t read it immediately — she was working on another project Two days later, Jacklin read a part of the book (“It’s very long, you know”), and although she had been warned by her sister, Pam Jacklin, who had been involved with Wired from its inception, to expect the worst, Judy was “hopeful for the rest of the book. It didn’t seem terribly negative. But two days later, I read more. By then, it was pretty disturbing.”

It wasn’t a fair portrait of John, she said. There was no joy in the book, no balance. “I loved John because he was warm,” Jacklin said. “He was a very likable person. He had a terrific presence, and Woodward missed all that.” Wired, Jacklin claimed, was only about drugs and madness, and it wasn’t even accurate. “People claim it’s all facts,” she said. “It’s not all facts. It’s a bunch of people’s opinions and memories put forth as facts. And when someone like Bob Woodward, who everyone thinks of as an ace reporter, uses these people as expert sources, it becomes very frightening. He’ll quote someone like, say, Carrie Fisher, who was on the Blues Brothers set maybe ten days, saying, ‘Well, it looked like he was doing four grams a day.’ Well, we’re talking about my life here. I was there. He may have it that way in his notes, but it’s wrong.”

In the beginning of June, Jacklin put forth her arguments in People magazine, and later on the Today Show and Good Morning America. She often sounded confused, but her friends were less conflicted.

“Trash,” proclaimed Dan Aykroyd in the June 7th Philadelphia Inquirer, while on the road to promote Ghostbusters. “Exploitation, pulp trash…. I think to delve into that sordid, tragic story in the way [Woodward] did was unforgivable. None of us knew what he was really up to…. Initially, I was against doing a book of any kind. But it was Bob Woodward, you know, and I thought, hey, this might actually turn out to be a class act.”

“The man is a ghoul,” claimed Jack Nicholson later in Interview magazine, “and an exploiter of emotionally disturbed widows…. Here’s a guy who has a reputation, right? I’ve obviously seen this kind of work before — it’s the lowest… This guy is actually finished. I believe that.”

The hue and cry was heard even from celebrities not in the book (Taxi‘s Tony Danza: “What I didn’t like about the Bob Woodward book is that it didn’t show what a great guy John was”) and those who were only marginal characters (comedian Richard Belzer: “He betrayed Judy’s trust; she went to him because he’s so respected, so John’s life would not be sensationalized, and now that’s what happened”).

Shortly after Aykroyd’s interview in Philadelphia, he stopped talking to print journalists. He refused an interview with People, reportedly complaining that the magazine had portrayed Jacklin as a “whining, hysterical widow,” even though her byline had appeared on the story. Aykroyd clearly wanted out of the picture and stayed away from Wired in subsequent TV interviews.

In the meantime, Bob Woodward was busily expressing shock and surprise over what could now be officially termed the Wired Controversy. By early June, he was out promoting the book, which had been excerpted in Playboy and serialized in about fifty newspapers (including, of course, the Washington Post, Woodward’s mother ship).

Wired was receiving mostly negative reviews — the New York Times book-review section attacked Woodward’s “magnifying-glass-on-credit-card-receipt approach” as extremely ineffectual; Kirkus Reviews called Wired a “pointless docudrama”; and Time slashed away, claiming, “The entire book is basically an exercise in casting: get the country’s star investigative reporter to tackle ‘the unanswered questions’ about the grubby death of America’s favorite counterculture comedian…. But Wired, so full of details, is so short on insight that Belushi never becomes any larger or more understandable than a gifted guy who pigged out on success.” The slagging only fueled the ruckus — and increased sales. Wired, it appeared, had a powerful allure. After an original print run of 175,000 copies, Simon and Schuster, Wired‘s publisher, rushed another 100,000 into print.”

Bob Woodward lied about Nixon, Watergate, the war in Iraq, Iran-Contra and the late comedian John Belushi. Why should we believe his latest lies about President Donald Trump?