The Second Great Awakening in the Pacific Northwest

While America was expanding westward, the son of a Spokane Indian chief helped bring the Gospel to the Indians of the Pacific Northwest.

By Rob Chase

Around the time we were fighting the American Revolution, a smallpox plague hit the Spokane Indians in the inland Pacific Northwest of North America. Approximately a third of the Spokane Tribe perished in a matter of weeks. Their head chief, Circling Raven, climbed Mount Spokane to seek the Creator, “He Who Lives Above,” for an answer as to why this had happened.

After fasting and praying for many days, Circling Raven received a vision. Very soon, men with white skin would visit the Spokanes, and they would be bearing piles of leaves bound in hide that would tell them more about the Creator.

When Circling Raven returned to his people, he told them of his vision. He told them to be patient and wait for the white men.

Around 1800, the tribe woke up to see a strange phenomenon. It was as if a dry snow had covered everything. They did not know that Mount St. Helens had exploded in the Cascade mountain range (as it would later in 1980). It was seen as an omen. The Spokanes were afraid this must be the end of the world. Circling Raven comforted them by telling them the white men must come first. He then told them the part of the vision he had been afraid to tell them. The white men would come by the hundreds of thousands and be more powerful. They must be friendly to the white men and trust their Creator, and then the end would come.

Arrival of the White Man

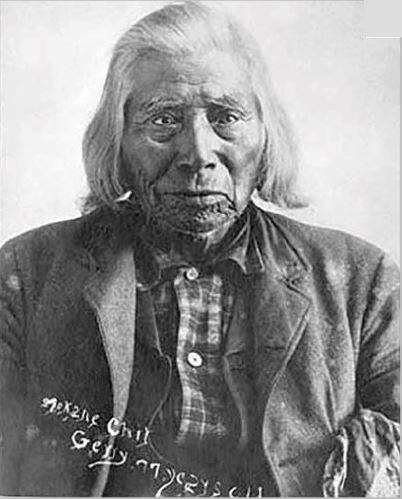

In 1811, fur traders with the North West Company under David Thompson came to the Spokanes and established a trading post at Spokane House. They were anything but illuminating on the subject of the Creator, as they were mainly interested in making their fortunes in the fur trade and going back home. That same year, the new Spokane chief, Illim-Spokanee, fathered a son, Slough-Keetcha, the meaning of whose name has been lost.

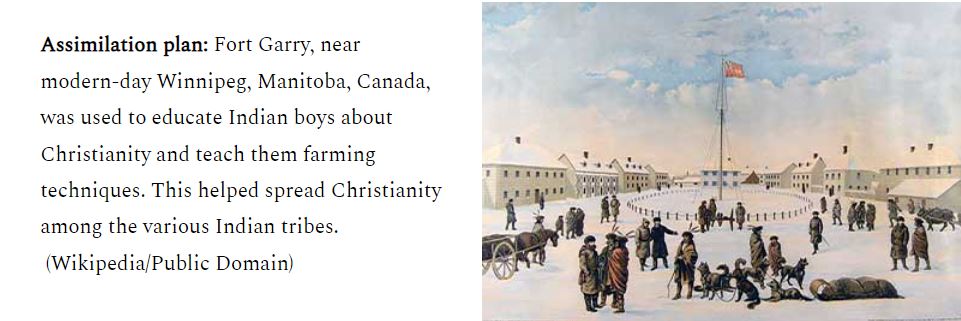

In 1825, George Simpson, governor of the Northern Department of the Hudson’s Bay Company, asked the chiefs of the various tribes in the area to send one of their sons to Fort Garry in the Red River Colony (modern-day Winnipeg) to learn about Christianity and farming techniques. Simpson’s goal was not so much to spread Christianity as it was to get the tribes to stop fighting each other and be more productive for the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Illim-Spokanee volunteered his son Slough-Keetcha, since he was a quick learner and wanted to be one of the boys sent to Red River. Governor Simpson baptized him into the Anglican faith and named him Spokane Garry, after the deputy governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, Nicholas Garry.

Along with Spokane Garry, another boy, the son of Chief Le Grande Queue of the Kutenais, went on the long journey to the Red River Colony. Simpson named the Kutenai boy Pelly, after another employee. The two boys became fast friends, and became fluent in English and French. They learned farming techniques and the Anglican doctrine and were baptized again; this time, it was their choice.

After four years, the boys returned to their peoples with a desire to spread Christianity within their own, as well as in surrounding, tribes. When the first Christian missionaries arrived in the Pacific Northwest eight years later, they were surprised to find most of the tribes in the area adhering to a form of Christianity. Although Pelly had died from falling off a horse shortly after returning to his tribe, Garry was the catalyst for the Second Great Awakening in the Pacific Northwest among the Spokane, Flatheads, Cayuse, Nez Perce, Yakima, and other smaller tribes.

For several years, Garry taught from the King James Bible and the Anglican Book of Common Prayer as best he could. He emphasized being good and avoiding evil; observing Sundays, Christmas, and Easter; that Heaven and Hell are forever; that Christianity is a choice; and that any person can be saved by faith in Jesus Christ and good works. He noted from John 6:29 that “Jesus answered and said unto them, ‘This is the work of God, that ye believe in him whom He hath sent.’” (Although Anglicans retained much of the ceremony of the Roman Catholics, they agreed with the other Reformers on the concept of “sola fide” [faith alone].) On weekdays, he would read from the Bible and teach agriculture.

In 1838, Presbyterian missionaries Elkanah Walker and Cushing Eells came to the Spokanes, while Henry Spalding ministered to the Nez Perce and Marcus Whitman to the Cayuse. They were astonished that most of the Indians already observed a semblance of Christianity. Their attitude was that while Garry could help them, they were the experts and would take a commanding role. They were followed by the Catholic Black Robes in 1841, led by Jesuit Priest Pierre-Jean De Smet, who ministered to the Coeur d’ Alene and Upper Spokane Indians.

The different messages expressed by the Roman Catholics and the Protestants led to confusion on how the Indians were to worship the Creator. Garry helped the new missionaries as best he could, but their criticisms of his simple Anglicanism and their belief that all men were steeped in evil was something he was unable to compete with theologically. Garry had not been taught that gambling, dancing, smoking, and drinking were evils, for instance. The Indians were now questioning Garry’s version of Christianity. Garry had first married a San Poil maiden, Lucy, as an arrangement, but afterward, he met a Umatilla girl, Nina, half his age, and they fell in love and were also married. Garry compared his situation to the Hebrew fathers, but was later told that those men were living in a different dispensation and that bigamy was now unacceptable.

Although some Indians became devout Christians, most preferred the white fur traders with their gifts and gambling. By this time, the Indians were beginning to understand that destruction of their long-honored indigenous ways was taking place, and as smallpox plagues spread through the area, further reducing their numbers while leaving most whites unaffected, they became suspicious. In 1847, Marcus and Narcissa Whitman were killed at their Walla Walla mission by Indians who suspected they had precipitated the plague on purpose. It didn’t help that Narcissa would not allow Indians into her house. The fledgling military authorities evacuated the other Protestant missionaries, but left the Black Robes, who had had some success with inoculating their members against smallpox. Father Joseph Joset especially looked out for the welfare of his flock.

Garry drifted away from his ministry, as waves of doubt understandably caused him to question his role as a teacher. Most of the other young Indians who were taught Anglicanism at Red River had suffered early deaths, and no Anglican missionary was sent to help him. He began to concentrate on building his farm. Lucy had left him, but Nina was his comfort.

Darkening Outlook

The early 1850s left the tribes relatively untouched, but there was trepidation about the times ahead. This darkening outlook accelerated in 1855 when the new governor of Washington Territory, Isaac Stevens, arrived in Olympia and immediately called a council in Walla Walla to form treaties with the different tribes to carve out reservations where the Indians would be permanently placed.

The tribes wanted to make a good showing, and an estimated 5,000 warrior-class men showed up. Fairness was not high up on Governor Stevens’ agenda, however, as he mostly wanted to hurry up and settle the tribes on their reservations before the Northern Pacific Railroad came through.

The chiefs had already heard from Indians from the East, who had dealt with the “Bostons,” that the white newcomers could be counted on to lie to buy time.

Stevens, who graduated at the top of his class at West Point and was wounded in the Mexican-American War, got cross-ways with the Army regulars, who were more sympathetic to the Indians they were commissioned to protect. Stevens relied a lot more on the local militias, who were impatient with Native resistance, which led to many massacres and turmoil. Garry always was in favor of peace and negotiation.

Stevens crossed and crisscrossed the Northwest, making treaties as if taking ancestral lands and making false promises were normal things for him to do. His ultimate goal was to prepare the territory for the Northern Pacific Railroad and the “Manifest Destiny” of Western civilization. He ran for Congress to represent the territory, was elected, and got involved in the brewing Civil War. He went on to a glorious death in the Second Battle of Bull Run.

In May of 1858, Lieutenant Colonel Edward Steptoe took a force of 164 men north of the Snake River into Spokane Indian land, despite the fact that the Spokanes had previously warned the Army to stay south of the Snake River. Very soon, the soldiers engaged nearly a thousand Indians from the various tribes, and were surrounded on a hill and in danger of being annihilated. Chief Garry, Christian Chief Timothy of the Nez Perce, and Jesuit Father Joset tried to broker peace, and eventually helped the detachment escape in the dark of night. The event was an embarrassment to the military, and caused them to lose their previous sympathetic stance toward the Indians and seek revenge.

Under Colonel George Wright, the Army spent a few months waiting for supplies and constantly drilling. Wright had been wounded in the Mexican-American War and carried from the field by officers, including the aforementioned Isaac Stevens. Wright was itching to enter the Civil War, where he might have been another Grant or Sherman. His requests for service in the war were denied, and he was kept in the West, away from any glory. He was known for his cruelty and for breaking his word to enemy combatants, and even the soldiers who accompanied him found his conduct questionable.

Wright’s forces soon numbered nearly a thousand men with brand-new Sharps rifles, which could hit an enemy at 600 yards. On August 5, hell-bent on revenge, the column set out from Fort Walla Walla, 150 miles from Spokane. This time, their numbers included 190 cavalry, 400 infantrymen, 90 rifle brigades, 200 civilian packers, and 33 Nez Perce scouts.

The two sides clashed at Four Lakes, west of Spokane Falls. With their new Sharps rifles, the infantry killed around 20 and wounded 50 Indians from a range of 400-500 yards, before the Indians could even engage. The Indians attacked again on September 5 at Spokane Plains, near the present-day Spokane Airport, with the same results. Dozens of Indian warriors had been killed or wounded, while Wright’s entire force only suffered one minor casualty. The gallant braves had the fight knocked out of them, and there seemed to be no alternative but to stay out of the way. They grudgingly had to admit Garry had been right.

Wright’s forces continued the march up the Spokane River, capturing and slaughtering a herd of around 900 Indian ponies. The soldiers also burned all the stores the Indians had been saving for the winter, meaning the Indians would likely starve that winter. Worse yet, Colonel Wright invited Indians to his camp to parlay. If he deduced they were part of the resistance, he hanged them immediately.

Colonel Wright was hailed as a hero around the country. The way was now open for settlers to homestead on the Washington Plateau without much resistance. It is still debated whether Wright actually saved lives with his savagery aimed at shortening the expected period of Indian resistance.

Overcoming Adversity

Garry was vindicated, but heartbroken. He and Father Joset helped as many Indians as possible get through the winter and not starve to death. Many suffered a loss of identity and self-worth, and many took to drinking. White men’s diseases took their toll. As most of the white immigrants were men, Indian women became barter, as they were practically the only women around.

Garry decided to use cooperation and friendliness, and helped the military find routes for delivering mail or new roads to better reservations for the Indians. He also started working his own farm in northeast Spokane, and soon had plenty of crops and livestock to share. He petitioned for a reservation that would be isolated from the whites and on native Indian lands. At that time, there were still very few whites between Spokane Falls and the Columbia River, from which the salmon harvest came, which made up a principal portion of the natives’ diet. Eventually, salmon runs would be decimated by pollution and canneries in the lower Columbia.

In 1870, Garry started up his church again on a bluff on the north side of what would become the city of Spokane. A Christian revival seemed like the best antidote to the despair of the Spokane Tribe. There was still no Anglican presence to help him, but he held services in the Anglican fashion as best he could. The rivalry between Protestant and Catholic missionaries intensified again as Reverend Henry Spalding returned to Lapwai. Garry tried to cooperate with the Presbyterian Spalding, and invited him to speak to his congregation. Although Spalding went so far as to refer to Garry as his brother, he soon became ill and died. His replacement, Henry T. Cowley, seemed to be more interested in real-estate opportunities than missionary work, and began buying up what was to become downtown Spokane. Cowley referred to Garry as “a suspicious, deceitful, and substable character, and in the present state of affairs, a very injurious influence.”

In 1877, the Nez Perce went on the warpath and asked the Spokane Tribe for help, but Garry knew it would be another lost cause. The way of peace at least held some promise.

In 1881, the Spokane Reservation was created as a subdivision of the Colville Reservation. It had been reduced from 3,000,000 acres of recognized tribal land to 157,000 acres, 90 percent of which was held in trust by the U.S. government. Annuities promised to the chiefs were never paid. Also in 1881, the Northern Pacific Railroad arrived in Spokane, bringing thousands of settlers. In 1883, gold and silver were discovered in the Coeur d’Alenes, bringing thousands of miners. An Episcopal (the new name for the Anglican church in America) minister finally arrived in 1884, but like Cowley, he seemed more interested in buying up land than evangelism. Added to this religious confusion were the emerging Dreamer-Prophets of the East Washington Plateau, such as Skolaskin of the San Poils and Smohalla of the Wanapums. Like their Great Plains counterparts, they combined indigenous, Christian, Spiritist, Latter-Day Saint, and even Shaker beliefs into apocalyptic prophecies that Providence would supernaturally aid the Indians in taking back their lands.

Garry didn’t want to go to the reservation. He wanted to own his land in northeast Spokane and die where he had been born. As long as Garry improved the land he lived on (which he did), it was considered his. One day, after returning from a fishing trip, Garry found a squatter on his land. The squatter begged Garry to let him harvest his crop, which he allowed him to do. In the meantime, the squatter sold the land to a nearby established neighbor. Garry contested the theft, but as Indians rarely won in court in those days, the land he had worked for 30 years was awarded to his neighbor.

Garry left and camped by the Spokane River west of town under the Sunset Bridge with his wife and daughter, who would do washing for the townspeople. He had never received a dime of the annuities promised to him for agreeing to the treaty. Kids would throw rocks off the bridge at his teepee for fun. One kind landowner let him move his teepee to some land he owned in Indian Canyon, and Garry died there on January 13, 1892.

Garry witnessed, and was a significant player in, the settling of the American Northwest. Like the fictional Jack Crabb in Thomas Berger’s novel Little Big Man, he knew many of the historical fellow players of his time, such as Chiefs Joseph, Kamiakin, and Moses. He also knew many future Civil War figures, such as McClellan, Sherman, Sheridan, and possibly Grant, as well as famed botanist David Douglas and, probably, celebrated mountain man Jedediah Smith.

In 1810, the year before Garry was born, white trappers with the Hudson’s Bay Company had made contact with the Spokanes, heralding the prophecy of Circling Raven. Garry lived long enough to see the hills surrounding Spokane Falls lit up with the growing town’s gas lights instead of the ancient stars.

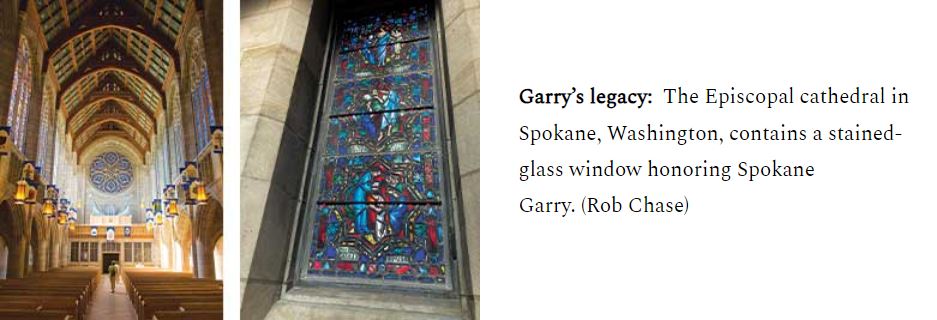

In 1924, a large Episcopal cathedral was built in Spokane, and a stained-glass window was installed in Garry’s honor.

Garry could be compared to the biblical Job — a man who had tried to do the right thing by his God but ended up with most people despising him. Like Job, Garry kept his faith to the end. Found among his papers was this poem he had written:

I am so glad our Father in Heaven

Tells of His love in the book He has given.

Wonderful things in the Bible I see

This is the dearest that Jesus loves me.

I am so glad that Jesus loves me

Jesus loves me, Jesus even loves me

If I forget Him and wander away.