Brett Kavanaugh rides to the Biden administration’s defense in a big First Amendment case

The Supreme Court’s center right appears increasingly frustrated with the judiciary’s far right.

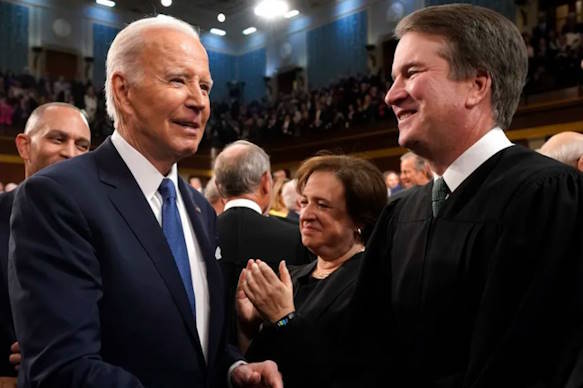

President Joe Biden greets Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh before delivering the State of the Union address on February 7, 2023, in Washington, DC. Jacquelyn Martin/Getty Images

There are several recent signs that the federal judiciary’s center right is losing patience with its far right.

Last week, a policymaking body within the judiciary announced new steps to combat “judge shopping,” a practice that has allowed Republican litigants to choose to have their cases heard by partisan judges who are well to the right of even the median Trump appointee. The Supreme Court has also heard several cases in its current term where it appears likely to reverse rulings made by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, a MAGA stronghold that frequently hands down decisions that appear designed to sabotage the Biden administration.

On Monday, the Supreme Court held oral arguments in one of these Fifth Circuit cases, known as Murthy v. Missouri, where the lower court handed down a sweeping injunction forbidding much of the federal government from having any communications at all with social media companies. A majority of the justices appeared very unlikely to sustain that injunction on Monday, with Justice Brett Kavanaugh repeatedly noting that the Fifth Circuit’s approach would prevent the most routine interactions between government officials and the media.

Murthy was one of two cases heard by the justices on Monday involving so-called “jawboning” — cases where the government tried to pressure private companies into taking certain actions, without necessarily using its coercive power to do so. The other case, known as National Rifle Association v. Vullo, involves a fairly egregious violation of the First Amendment. Based on Monday’s argument, as many as all nine of the justices may side with the NRA in that case. (You can read our coverage of the NRA case here.)

Most of the justices, in other words, appeared eager to resolve both cases without significantly altering their Court’s First Amendment doctrines, and without disrupting the government’s ability to function. That’s good news for the NRA, but also good news for the Biden administration.

So what is the Murthy case about?

The general rule in First Amendment cases is that the federal government may not coerce a media company into changing which content it publishes, but it can ask a platform or outlet to remove or alter its content. Indeed, as Kavanaugh pointed out a few times during the oral argument, if the government were not allowed to do so, White House press aides and the like wouldn’t be allowed to speak to reporters to try to shape their coverage.

In Murthy, various officials throughout the federal government had many communications with major social media platforms, where the officials either asked the platforms to remove certain content or provided them with information that convinced the platforms to do so.

These communications concerned many topics. The FBI, for example, frequently contacts social media platforms to warn them about criminal or terroristic activity that is occurring online. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) flags social media content for the platforms that contains election-related disinformation, such as false statements about when an election will take place. The White House sometimes asks social media companies to remove accounts that falsely impersonate a member of the president’s family.

Many of these communications also involved government requests that the platforms pull down information that contains false and harmful health information, including misinformation about Covid-19. And these communications were center stage during the Murthy oral argument — the Murthy plaintiffs include several individuals who are upset that their content was removed because the platforms determined that it was Covid misinformation.

These plaintiffs were able to identify several examples where government officials were curt, bossy, or otherwise rude to representatives from the social media companies when those companies refused to pull down content that the government asked them to remove. Notably, however, neither these plaintiffs nor the Fifth Circuit identified a single example where a government official threatened some kind of consequence if a platform did not comply with the government’s requests.

Instead, the Fifth Circuit appeared to complain about the fact that the government has so many communications with social media companies. It claimed that the Biden administration violated the First Amendment because government officials “entangled themselves in the platforms’ decision-making processes,” and ordered the government to stop having “consistent and consequential” communications with social media platforms.

It’s unclear what that decision even means — how many times, exactly, may the government talk to a social media company before it violates the Fifth Circuit’s order? — and at least six of the justices appeared frustrated by the Fifth Circuit’s ham-handed approach to this case.

The two justices who’ve worked in senior White House jobs appeared especially dismissive of the Fifth Circuit’s position

Justices Elena Kagan and Kavanaugh seemed especially frustrated with the Fifth Circuit’s attempt to shut down communication between the government and the platforms, and for the same reason. Both Kagan and Kavanaugh worked in high-level White House jobs — Kagan as deputy domestic policy adviser to President Bill Clinton, and Kavanaugh as staff secretary to President George W. Bush — and both recoiled at the suggestion that the White House can’t try to persuade the media to change what it publishes.

Kavanaugh, a Republican appointed by Donald Trump, even rose to the government’s defense after Justice Samuel Alito attacked Biden administration officials who, Alito claimed, were too demanding toward the platforms.

After Alito ranted about what he called “constant pestering” by White House officials who would sometimes “curse” at corporate officials or treat them like “subordinates,” Kavanaugh said that, in his experience, White House press aides often call up members of the media and “berate” them if they don’t like the press’s coverage.

Similarly, Kagan admitted that “like Justice Kavanaugh, I’ve had experience encouraging people to suppress their own speech” after a journalist published a bad editorial or a piece with a factual error. But this sort of routine back-and-forth between White House officials and reporters is not a First Amendment violation unless there is some kind of threat or coercion. Why should the rule be any different for social media companies?

So Benjamin Aguiñaga, the lawyer trying to defend the Fifth Circuit’s order, arrived at the Court this morning facing an already skeptical bench. And his disastrous response to a hypothetical from Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson only dug him deeper into a hole.

Jackson imagined a scenario where various people online challenged teenagers to jump out of windows and that there actually was an epidemic of teens seriously injuring themselves by doing so. Could the government, she asked, encourage the platforms to pull down content urging young people to defenestrate themselves?

Aguiñaga’s answer was “no” — an answer that provoked an incredulous Chief Justice John Roberts to restate the question and ask Aguiñaga to answer it again. And yet the lawyer still clung to his view that the government cannot encourage Twitter or Facebook to remove content urging people to hurl themselves out of windows.

It is likely, for what it’s worth, that at least two justices will dissent. Last October, the Court temporarily blocked the Fifth Circuit’s Murthy decision while this case was being litigated before the justices, but it did so over objections by three justices: Alito, plus Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch.

On Monday, Gorsuch did ask a few questions suggesting that he may have reconsidered his previous position because he now views the Fifth Circuit’s injunction as too broad, but Thomas and Alito appeared determined to back their fellow members of the judiciary’s far right.

So, while an alliance between the Court’s center left and its center right appears likely to hold in the Murthy case, that could change rapidly if former President Donald Trump is returned to office and gets to replace some of the current justices with members of the Fifth Circuit (or with other judges who share Thomas and Alito’s MAGA-infused approach to judging).

But for the time being, at least, most of the justices appear to recognize that the government needs to function. And that means that the Fifth Circuit’s attempt to cut off communications between the Biden administration and the platforms is likely to fail.

Ian Millhiser is a senior correspondent at Vox, where he focuses on the Supreme Court, the Constitution, and the decline of liberal democracy in the United States. He received a JD from Duke University and is the author of two books on the Supreme Court.

From vox.com