Wishing you a joyous Christmas

Compiled by Steve Dunham

Then the angel said unto them, Be not afraid: for behold, I bring you glad tidings of great joy, that shall be to all the people. Unto you is born this day in the city of David, a savior, which is Christ the Lord. Luke 2;10

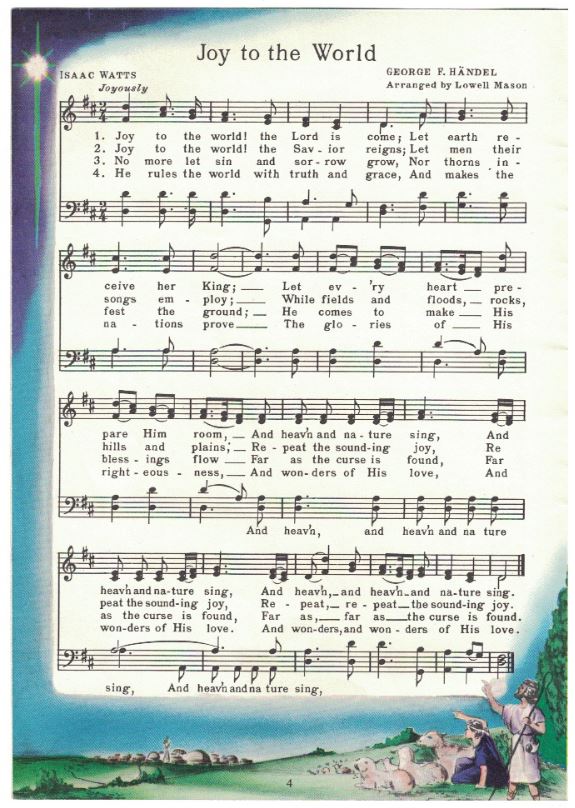

“Joy to the World” is a Christmas carol written by Isaac Watts in 1719 based on Psalm 98. We will hear and sing it again this Christmas season. Yet every year there seems to be less joy in the world. Sins and sorrows grow as we continue to deal with more wars, strife, crimes and death. Is it because we have not believed the simple yet profound message of this song, “The Lord is come; Let earth receive her King?” William Penn the founder of Pennsylvania said “ Those who will not be governed by God will be ruled by Tyrants.” Our founding fathers believed Isaac Watts and William Penn. They replaced King George with King Jesus our Creator who has endowed us with many unalienable rights. Today our rejection of God’s governance over us has led to an ever expanding governmental tyranny fueled by the curse of evolution, secular humanism, transgenderism, abortion, socialism, communism, sexual perversions, democracy, and the Mother Earth climate narrative. Heaven and nature will sing, God’s blessings will flow and we will enjoy the wonders of his love only if our hearts prepare him room to once again become our Lord, Savior and King. Isa.33;22. 2 Chronicles 7;14

Below is the Joy to the World Christmas carol and a history of Isaac Watts and “Give’em Watts, boys.”

Dear Liberty,

The British troops continued to push the colonists further into Springfield, New Jersey. With five Red Coats for every one Patriot, the odds seemed overwhelming. However, the Americans continued to present a powerful defense, giving their opponent a demanding fight. That is until they ran out of wadding, or paper, to wrap their gunpowder in before placing it in their muskets. Without that wadding, they were virtually unarmed.

As the fight continued, Reverend James Caldwell rallied the soldiers as he rode among the troops. Upon hearing the men yelling for more wadding. Caldwell quickly raced his horse to the church and grabbed a stack of hymn books written by the prominent hymn-writer of the time, Isaac Watts. Hurrying back to the fight, Caldwell tossed the hymn books to the soldiers. As the men started ripping the pages out to use as wadding, Caldwell shouted, “Give ‘em Watts, boys! Put Watts into ‘em.”

With the necessary supply of paper, the colonists beat back the Red Coats and won the Battle of Springfield on June 23, 1780. Following the defeat, British General Henry Clinton decided to focus on the South, never entering New Jersey or the North again. However, on their way out of Springfield, the British set fire to the buildings, destroying all but four of them. Included in the casualties was the Presbyterian Church Caldwell retrieved the hymnals from, yet the good reverend’s words to the soldiers would live on through history even until today.

Following the Reformation, the fight for religious freedom struck a chord with those all throughout Europe. (see The Knock Heard ‘Round The World and Here I Stand) Isaac Watts, born July 7, 1674, in Southhampton, England, experienced this first hand as his father spent considerable time in prison as a religious dissenter. His parents dearly loved God’s Word, yet rejected being forced to conform to the Church of England. (see England’s Luther)

Watts learned Latin at age five and knew Greek, French, and Hebrew all by age thirteen. In addition, his mother spent over a decade teaching him to write rhyme and verse. While Watts appreciated the doctrines and services of his church, the music lacked passion for him. Martin Luther understood the importance of the music and hymns in the church as they should be used to teach the congregation, especially the children, as much as the sermon does. Therefore, he wrote multiple hymns, including his most famous, “A Mighty Fortress,” inspired by Psalm 46. However, most other Protestant churches followed John Calvin’s lead, who preferred only metrical psalms.

After years of complaining to his family about the dull and sterile music, Watts’s father finally challenges, “Why don’t you give us something better, young man!” Within a week, the 15-year-old composed his first hymn, “Behold the Glories of the Lamb,” which he immediately gave to the church. The congregation’s overwhelming approval lit a fire in the “Father of English Hymnody” that would not be soon extinguished.

Watts’s notable brilliance generated several offers from wealthy townspeople to provide his expenses to Oxford or Cambridge. Watts refused the generous gifts knowing such universities would have prepared him for a ministry in the Anglican Church, or Church of England. Instead, he opted for Dissenting Academy, a leading Nonconformist school in Stoke Newington in north-east London, at age 16.

Watts accepted a position of pastor of London’s Mark Lane Independent Chapel in 1702, but resigned his position in 1712 due to health reasons. However, his hymn and psalm writing continued. While still at the chapel, he published Hymns and Spiritual Songs in 1707, which contained such beloved English hymns as “When I Survey The Wondrous Cross.” While he did not appreciate the metrical portion of his church’s songs, he loved the psalms. Watts contended “They (psalms) ought to be translated in such a manner as we have reason to believe David would have composed them if he had lived in our day.” Therefore, he published Psalms of David Imitated in the Language of the New Testament in 1719. Within its pages contained Psalm 98 composed as “Joy to the World.” Psalm 72 inspired “Jesus Shall Reign Where’er the Sun” and “O God Our Help in Ages Past” is Psalm 90. Other well-known Watts hymns include, “I Sing the Mighty Power of God,” “When I Can Read My Title Clear,” “Alas and Did My Savior Bleed” (also known as, “At the Cross”), “Am I a Soldier of the Cross?” and “Come We That Love the Lord.”

Understanding David fought against personal foes, such as Saul, Watts addressed the average Christian’s attackers: temptation, sin, and the ultimate accuser, Satan. Watts argued, “Where the flights of his faith and love are sublime, I have often sunk the expressions within the reach of an ordinary Christian.” His hymns also remind us of the Glory of Christ and to lay our worries at the foot of the cross. Though his illness took him out of the pulpit, his hymns have taught millions of the love of God and His grace through His son, Jesus.

In addition to his 600 songs, Watts wrote three volumes of sermons, articles on philosophy, psychology, and astronomy, and almost 30 theological papers. Watts composed the very first children’s hymnal, Divine and Moral Songs for Children in 1715, which included songs instructing children on the 10 Commandments, truths about the Bible, creation, eternal life and death, and how to lead a Godly life, all based on scripture. He also authored a textbook, which remained a prominent standard work on logic for decades.

Unmarried and childless, Watts died on November 25, 1748, at age 74 at the home of a dear friend of which he lived for over 25 years. A nonconformist and dissenter of the Church of England like his father, Watts was forbidden to be laid to rest within London’s city limits. Therefore, he was buried outside the city walls in Bunhill Fields.

Watts not only made an impact in Britain, he also greatly influenced America. As Englishmen seeking freedom, including religious freedom, traveled to the New World, many usually brought two items with them: The Bible and their Watts Hymnal. Reverend Cotton Mather, who along with his father Reverend Increase Mather worked to end the Salem Witch Trials, enjoyed a lengthy long-distance friendship with Watts. (see Time Of Insanity) Methodist founders, Charles and John Wesley, greatly admired Watts and used his works. In the colonies, Jonathan Edwards and George Whitfield, ushered in “The (First) Great Awakening,” using the Watts Hymnal as a guide, which Benjamin Franklin published in his printing shop. (see The Forgotten Founding Father)

Ministers in America’s pulpits influenced by “The Great Awakening” and the Watts Hymnal, preached of freedom and liberty. Known as the “Black Robe Regiment,” these ministers, such as Reverend John Peter Gabriel Muhlenberg (see Who Among You Is With Me?) and Reverend Caldwell, preached the liberating Gospel of Jesus Christ. When the time came to defend their religious and other freedoms, they also led their congregations onto the battlefield. Black evangelists at the time, including Harry Hoosier (see Hoosier Daddy) and John Marrant (see Instrument Of God), also used the Watts Hymnal as they preached the Good News of Jesus Christ to blacks, both free and enslaved, and Native Americans. Watts’s influence went well into the 19th Century as Reverend Charles Spurgeon included multiple pieces by Watts in his own Our Own Hymn-book in 1866. (see Prince Of Preachers)

If not for Caldwell’s quick thinking during the Battle of Springfield, it may have ended up in a hard fought defeat due to exhausted ammunition supplies, like the Battle of Bunker Hill. (see Defining The American Spirit) Caldwell’s charge of “Give ‘em Watts, boys,” was quickly cemented into history, largely due to a poem published later that year by Francis Bret Harte entitled Caldwell Of Springfield. People still use Caldwell’s explanation when they are angry. However, over time, his directive became “Give ‘em what for!”

Liberty, on multiple occasions throughout the Revolution, the Americans overcame overwhelming odds against the British. Given the superior munitions, training, and expertise of the Red Coats, some argue the Americas had amazing luck. Others, like myself, would content their victory was nothing less than Divine Providence. (see God’s Divine Providence) George Washington prayed on bended knee to God Almighty for guidance and mercy, which he and the colonists received. Something America desperately needs to do now.

America could very well benefit from Caldwell’s advise today, as we have grossly abandoned God and his instruction for us. As citizens attack each other over policies, ideologies, theologies, or just blinded anger, our best defense should be wrapped in the saving grace of Christ, as we find in Watts’s hymns, followed by a heavy dose of forgiveness. We could heal our nation by genuinely returning to the Gospel of Jesus Christ, starting in our churches. People are lost and are searching for answers. Satan knows this and is misleading them in every way he can. But the truth will set them free, and we must be ready and willing to give it.

The fight is hard Liberty, but the solution is easy. “Give ‘em Watts, boys!”

From a Mother, Liberating Letters, TheFactsPaper.com

Isaac Watts: The Man Behind the Hymns

In May 1789, Adam Rankin, having travelled from Kentucky to Philadelphia for the first General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, made the following query: ‘Whether the churches … have not faller into a great pernicious error by disusing Rouse’s versifications of David’s Psalms, and adopting … Watts’s imitation?’ The General Assembly gave Rankin a lengthy hearing and ‘endeavored to relieve his mind from the difficulties’, experiencing little success. They recommended ‘that exercise of Christian charity to those who differ from him in their views of this matter, which is exercised toward himself’. Further, they admonished him to ‘guard against disturbing the peace of the church on this head’. Thus, Isaac Watts, the writer of such hymns as ‘Alas and did My Saviour bleed’, ‘O God Our Help in Ages Past’, and ‘When I Survey the Wondrous Cross’ was approved and his Psalms of David Imitated in the Language of the New Testament were assured a permanent place in the worship of Presbyterians in America.

To people living today it seems strange that using Watts’ paraphrases of the Psalms in public worship would raise such grave concern. But to many living in the 18th century any singing in public worship other than the standard accepted translations of the Psalms was a return to the ‘popish’ forms of medieval Catholicism. Only occasionally were paraphrases or hymns allowed, and then just for special occasions and for specific congregations — not whole church bodies. Thus, for Isaac Watts to have written 600 hymns and versifications of the Psalms for use among the whole Protestant Christian world was a radical break with the past. It revolutionized the worship of dissenting churches and established the English hymn. In this light, Isaac Watts can truly be called the Father of the English hymn.

Isaac Watts was born in Southampton, England on July 17th, 1674, to Isaac and Sarah Watts. The oldest of eight children, he was brought up in the Nonconformist tradition of his parents. His father had been put into prison for his beliefs before his first son was born and was not released until the following year. Upon rejoining his family the elder Watts began instructing his son in the ways of religion which would have such an impact on his life.

During these early years, Isaac Watts began to display his skill for writing verse. Even before he was six years old he had written some verses. When his mother discovered them, she questioned whether he could have composed them. In order to assure her of his ability he produced an acrostic using his name:

I am a vile polluted lump of earth,

So I’ve continu’d ever since my birth;

Although Jehovah grace does daily give me,

As sure this monster Satan will deceive me,

Come, therefore, Lord, from Satan’s claws relieve me.

Wash me in thy blood, O Christ,

And grace divine impart,

Then search and try the corners of my heart,

That I in all things may be fit to do

Service to thee, and sing thy praises too.

As a child Watts also demonstrated a passion for learning. He began to study Latin at the age of four, Greek when he was nine, French when he was ten, and Hebrew when he was thirteen. At the age of six he came under the instruction of the Rev John Pinhorne, to whom he became closely attached as a dedicated student. During this time his father was again ‘persecuted and imprisoned for nonconformity for six months’, as his Memorandum tells us. Upon release the elder Watts was forced to live in London for two years, separated from his family. He sent his children a letter during this period which reflects the kind of upbringing they had received. He told them how much he missed them and that he remembered them always in prayer, adding, ‘Though it hath pleased the only wise God to suffer the malice of ungodly men … to break out against me … we must endeavour by patient waiting to submit to his will without murmuring’. He closed by assuring them that God’s ‘infinite wisdom’ was at work in his trials. Watts seems to have learned well from his father, for the same spirit of humility and submission before God characterized his attitude toward his own sufferings due to poor health throughout his life. Once during a severe illness, he wrote,

I know not but my days of restraint and confinement by affliction may appear my brightest days, when I come to take a review of them in the light of heaven.

Watts’ ability as a student became well-known, so that as the time approached for him to enter college a physician in Southampton, Dr John Speed, offered to pay for his preparation for the Christian ministry at an English university. Since only Anglicans could attend Oxford and Cambridge, Watts respectfully declined the offer, ‘determined to take his lot among the dissenters’. Having made this choke, at sixteen he went to the Academy of Newington Green, near London, to prepare for the ministry. The students there were under the tutelage of Rev Thomas Rowe, a Nonconformist minister. The quality of education was very high and Watts applied himself diligently. Samuel Johnson, in his Lives of the English Poets, wrote,

Some Latin Essays … written as exercises at this academy, show a degree of knowledge, both philosophical and theological, such as very few attain by a much longer course of study.

At the age of twenty, after completing his studies at the Academy, Watts returned to his family in Southampton where he stayed for two years engaging himself in reading, prayer, and meditation further to prepare himself to serve God in the church.

It was during this period that Watts became critical of the psalm-singing in the dissenting congregations, which was bound to the Sternhold and Hopkins version of the Psalms. He felt that the psalmody was crude and impoverished, lacking the dignity and grace that should be a part of Christian worship. His father’s response to his complaint was, ‘Try then whether you can yourself produce something better‘. Watts took up the challenge and the result was:

Behold the glories of the Lamb

Amidst his Father’s throne;

Prepare new honors for his name,

And songs before unknown.

Thus began the work for which Isaac Watts is remembered today. Having spent two years in Southampton preparing himself, in October, 1696, Watts went to become tutor to the son of Sir John Hartopp at Newington. There he taught and studied for five years, becoming assistant to Rev Isaac Chauncey, pastor of the Mark Lane independent church. He preached his first sermon on July 17th, 1698, his twenty-fourth birthday. His interest in improving the worship among independent churches continued throughout this period. In 1697 Watts’ friend and former classmate at Newington Green, Samuel Say, sent him and another classmate, John Hughes, his paraphrases of some of the Psalms. Hughes’ response was enthusiastic, commending Say for his effort and for rescuing ‘the noble Psalmist out of the butcherly hands of Sternhold and Hopkins’. Say seems not to have produced more, but the idea was given fresh impetus in Watts’ thinking. David Fountain, in his biography, Isaac Watts Remembered, writes that the ‘friendship between Say and Watts proved to be one of the influences which caused him some years later to apply himself seriously to the work of “imitating” the Psalms’. This period was also the beginning of Watts’ many struggles with extended periods of illness.

In April, 1701, Chauncey resigned as pastor of the Mark Lane congregation and the position was offered to Watts. After some indecision due to his poor health he finally accepted the call on March 8th, 1702. The church began to grow under Watts’ ministry at a time when many dissenting churches were in decline. Watts was an outstanding preacher in spite of his small stature and ‘thin’ voice. His dignified manner, clarity of thought, clear enunciation and his gifts in extemporary preaching combined to make him one of the ‘weightiest’ preachers of his day. Thus, the congregation multiplied and outgrew its Mark Lane meeting-house, moving to Pinners’ Hall, and finally, in 1708, to a brand new meeting-house at Bury Street. But poor health continued to plague Watts and soon it was necessary for the church to appoint the Rev Samuel Price to assist him.

The worst period of illness came in 1712 when Watts was struck by a severe sickness that lasted for most of the next four years. In 1713, believing that death was imminent, Watts recommended that Mr Price be appointed co-pastor.

In the Spring of 1714, Sir Thomas Abney, Lord Mayor of London and a member of Parliament, invited Watts to stay with his family for a week at their country home at Theobalds, hoping that the rest would aid him in his recovery. The visit extended into a residence which lasted thirty-four years, until Watts died. At the Abney home he was able to study and write, and it was there that many of his hymns were composed. The relationship between Watts and the Abney family was warm and he served the family well as a tutor to the Abney children, as a chaplain, and as a friend, while they cared for him during his times of illness. According to Dr Thomas Gibbons in his Memoirs of the Rev Isaac Watts, D.D., without such gracious hospitality he ‘might have sunk into his grave under the overwhelming load of infirmities’. Once when Watts commented to a visitor that a week’s visit had extended into a stay of thirty years, Lady Abney replied, ‘Sir, what you term a long thirty-years visit, I consider the shortest visit my family ever received’.

One of the greatest influences that inspired Watts to write hymns and scriptural paraphrases was his brother Enoch. In a letter to Watts in 1700 he writes, ‘In your last you discovered an inclination to oblige the world by showing it your hymns in print’, and urges him on in this, assuring him that it is not just out of brotherly admiration that he does so. He recounts how ‘mean’ the religious poetry of their day is and that in an age of dying devotion poetry like his is needed to ‘quicken and revive’ worship. He says that, ‘were David to speak English, he would choose to make use of your style’. Reminding Watts of the scandalous reputation the dissenters have for their ‘imagined aversion to poetry’.

Enoch exhorts him to publish his hymns in order that ‘these calumnies will immediately vanish’. Watts eventually took his brother’s advice to heart. In 1705 his book of poems, Horae Lyricae, which also contained twenty-five of his hymns, was published. In 1707 the first edition of Hymns and Spiritual Songs appeared. In 1709 a second edition went out with 145 new hymns added and revisions made of hymns in the previous edition. After this no further changes were made in the work, but more hymns appeared in later editions of Horae Lyricae and in other works. The Psalms of David Imitated in the Language of the New Testament, containing most of his paraphrases of the Psalms, appeared in 1719.

Watts’ hymns were received at a time when no one else had been able to succeed in this task. Previously hymns had been written only for specific congregations, not for use by the wider Christian public. Furthermore, hymns were only used on special occasions such as communion. One pastor, Benjamin Keach, used to place a hymn at the end of the service so that those offended by its singing could leave before it was sung. But people accepted and sang Watts’ hymns. In a letter to Watts, Phillip Doddridge wrote of a church in which he preached, ‘your Psalms and hymns were almost their daily entertainment’. Watts became so popular in England and America that people would sit down, refusing to sing, if a hymn by another composer was announced in the congregation. Thus Watts was able to effect a lasting change in the worship of the churches of his day.

After the publication of The Psalms of David, Watts continued to write, but almost all of his work was prose. He produced a book of children’s songs and poetry, a catechism for children, textbooks for college instruction, and a number of essays on theology and philosophy. Samuel Johnson writes of him, ‘Every man acquainted with the common principles of human action will look with veneration on the writer who is at one time combating Locke, and at another making a catechism for children in their fourth year’. But it is as a hymn-writer that Isaac Watts is remembered best — he is the Father of the English hymn. What many have called the ‘greatest hymn in the English language’ was penned by him:

When I survey the wondrous cross

On which the Prince of glory died,

My richest gain I count but loss,

And pour contempt on all my pride.

Christianstudylibrary.org. Mark Shuttleworth. The Banner of Truth. 1982