The DOE’s Press Release on Federal Building Standards Is Inaccurate and Misleading Puffery

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) recently released the pre-publication version of a proposed rule to “establish energy performance standards for the construction of new federal buildings, including commercial buildings, multi-family high-rise residential buildings, and low-rise residential buildings.” DOE’s press release boasts that its “first ever” greenhouse gas (GHG) emission standards for new federal buildings will “save $8 million per year in costs and decrease long-term carbon emissions.” From the release:

Buildings are a major source of greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S., and fossil fuels used in federal buildings account for over 25% of all federal emissions. If enacted within the proposed timeframe, DOE estimates that the new emission reductions requirements would save taxpayers $8 million annually in upfront equipment costs. Over the next 30 years, the new rule would reduce carbon emissions from federal buildings by 1.86 million metric tons and methane emissions by 22.8 thousand tons—an amount roughly equivalent to the emissions generated by nearly 300,000 homes in one year.

The foregoing verbiage is inaccurate and misleading puffery. Let’s start with the “first ever” claim. The proposed energy consumption-reduction standards are a “first” only in the sense that they were previously calibrated in thousands of Btu per square foot and now will also be calibrated in tons of carbon dioxide-equivalent (CO2e) emissions per square foot. The two metrics are mathematically convertible. Compliance with standards calibrated in thousands of Btu/ft2 automatically achieves compliance with the standards calibrated in tons of CO2e/ft2, and vice versa.

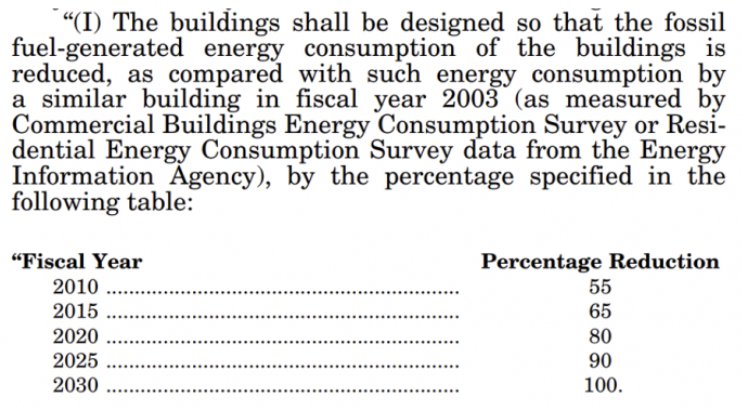

There is, however, no “first” in terms of policy substance. Section 433 of the 2007 Energy Independence and Security Act (EISA) requires DOE to adopt rules ensuring that federal buildings constructed or renovated during 2010-2030 meet the following fossil-energy reduction targets compared to similar buildings in 2003:

In short, since 2007, all new federal buildings are required to consume zero Btu of fossil-fuel energy by 2030, which also means zero tons of CO2e emissions.

So, why add a GHG-based metric to a 15-year-old program? Presumably, for the PR value of touting a “new” climate change initiative. But that is laughable, and not only because all the emission reductions were teed up in 2007 under a statute signed into law by President G.W. Bush.

No, what really punctures the balloon is the beyond-puny climate change mitigation DOE’s proposed standards will achieve.

According to the agency’s press release, over the next 30 years, the proposed standards will reduce CO2 emissions from federal buildings by 1.86 million metric tons. What impact would that have on global warming? The U.S. government uses the Model for the Assessment of Greenhouse Gas Induced Climate Change (MAGICC) to calculate the temperature effects of various emission scenarios and mitigation policies. Users can run MAGICC with different estimates of how much long-term warming results from a doubling of atmospheric CO2e concentration—a value known as equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS).

Here’s a reasonable back-of-the-envelope calculation:

- U.S. annual GHG emissions (CO2e): 6.6 billion tons (2019)

- Assume constant emissions for 30 years: 6.6 x 30 = 198 billion tons

- 1.86 million/198 billion = 0.0000094, or 0.00094 percent

- Assume an ECS of 3 degrees Celsius: MAGICC projects a temperature reduction in 2100 of 0.00001°C

For perspective, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) margin of error for measuring changes in global annual average temperature is 0.08°C. The climate mitigation achieved by the proposed standards is orders of magnitude smaller than the margin of error. The rule’s mitigation effects are way too tiny to be detected, measured, or verified.

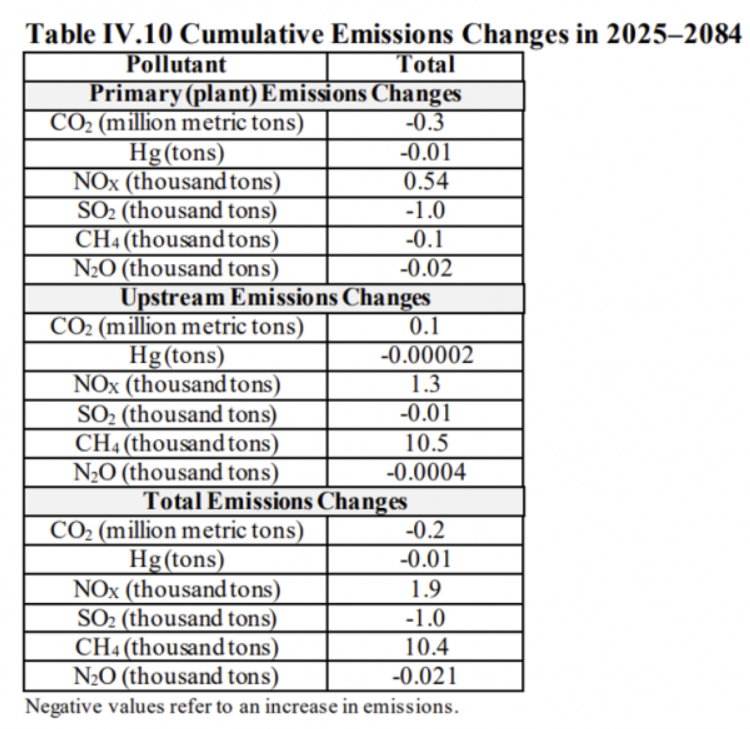

Actually, the proposed standards will avert even less than 0.00001°C of warming, because the press release is inaccurate. The proposed rule itself nowhere says the standards will avert 1.86 million metric tons (MMT) of “carbon emissions.” Rather, the proposal projects CO2 emissions to increase by 0.2 million tons over the 30-year period, as federal buildings become increasingly reliant on grid-based power for HVAC systems, hot water systems, cooking systems, or other systems or components currently powered by natural gas, diesel, or other on-site fossil fuels.

The proposal also estimates the standards will reduce methane (CH4) emissions by 10.4 thousand tons (p. 109), not 28.8 thousand tons, as the press release has it.

Quit Wasting Energy: How To Save Up To 90% On Your Utility Bill

According to the proposal, combining the CO2 increases with the methane savings and minor increases in nitrous oxide (N2O) “results in an overall net savings of CO2e emissions of approximately 0.07 MMT (million metric tons) CO2e” (p. 112). That figure is 26.5 times smaller than 1.86 MMT. Accordingly, any climate mitigation associated with the standards will be many times smaller than 0.00001°C.

Now for the misleading part. According to the press release, “the new emission reductions requirements would save taxpayers $8 million annually in upfront equipment costs.” Okay, but what about operating costs? Gas heaters and appliances are often cheaper to run than their electric counterparts. Here’s what the proposal says about the standards’ impacts on capital and operating costs (p. 121):

- “Capital cost impacts of the standards proposed in this case are estimated to be $7.89 million per year in decreased equipment costs.”

- “Annual operating disbenefits are estimated to be $8.26 million per year in increased equipment operating costs, primarily driven by the higher relative cost of electricity compared to natural gas.”

On balance, the proposed standards impose an annual net cost on taxpayers of $370,000. That is peanuts in the scheme of things, to be sure. Congress’s party-line enactment of the Inflation Reduction Act may increase federal climate-related spending and tax credits by between $369 billion and $800 billion and authorize up to $350 billion in new DOE loans.

Summing up, the federal-building emission reductions DOE’s press release attributes to policy innovation are the flip side of fossil-fuel reductions long required by statute. Benchmarking compliance in terms of tons CO2e as well as thousands Btu does not change the fact that the proposed standards are climatologically irrelevant. Contrary to the impression given in the press release, the net impact on taxpayers will likely be negative. Even if the standards did reduce federal building costs by $8 million annually, does anyone really believe U.S. households would see a dime of that in tax relief?

More importantly, the standards’ potential savings in federal building equipment costs are a drop in the bucket compared to the massive taxpayer burdens and liabilities created by the Inflation Reduction Act, to say nothing of the virtual energy taxes American households pay in higher energy costs due, in no small part, to the administration’s climate agenda.

Marlo Lewis is a senior fellow in energy & environmental policy at the Competitive Enterprise Institute.

From realclearenergy.org