Of the Natural Rights of Individuals

By TJ Martinell

Do people exist for the sake of government? Or is it the other way around? That’s the question James Wilson attempts to answer in his 1790 work, “Of the Natural Rights of Individuals.”

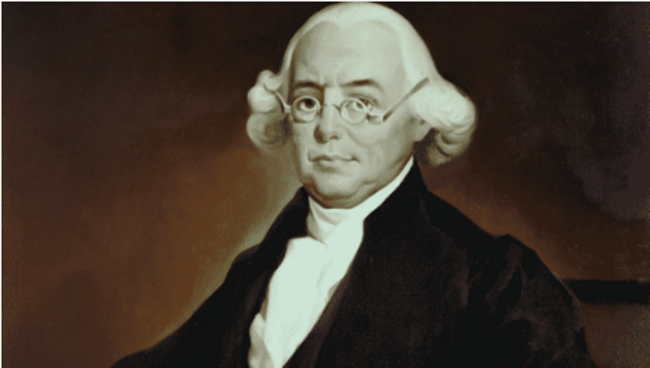

A signer of the Declaration of Independence and member of the Philadelphia Convention that drafted the U.S. Constitution, Wilson was elected twice to the Continental Congress and served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court.

He was highly respected as one of the top legal minds of his day.

“What was the primary and the principal object in the institution of government?” Wilson asked.

“Was it – I speak of the primary and principal object – was it to acquire new rights by a human establishment? Or was it, by a human establishment, to acquire a new security for the possession or the recovery of those rights, to the enjoyment or acquisition of which we were previously entitled by the immediate gift, or by the unerring law, of our all-wise and all-beneficent Creator?” [emphasis added]

Wilson clearly argues for the latter.

“Government, in my humble opinion, should be formed to secure and to enlarge the exercise of the natural rights of its members; and every government, which has not this in view, as its principal object, is not a government of the legitimate kind.”

In contrast, some of Wilson’s contemporaries such as Edmund Burke argued that when men “may secure some liberty, he makes a surrender in trust of the whole of it.” To Burke, men had to give up some rights to the government so it could protect others. Burke also believed that rights originated from government or tradition and were not inherent.

Wilson disputed this philosophy of giving up some freedoms to maintain others:

“The opinion has been very general, that, in order to obtain the blessings of a good government, a sacrifice must be made of a part of our natural liberty. I am much inclined to believe, that, upon examination, this opinion will prove to be fallacious. It will, I think, be found, that wise and good government — I speak, at present, of no other — instead of contracting, enlarges as well as secures the exercise of the natural liberty of man: and what I say of his natural liberty, I mean to extend, and wish to be understood, through all this argument, as extended, to all his other natural rights.”

Drawing from history, Wilson cites the feudal system as a textbook example of giving up rights to secure others, only to lose the others, too:

“The free and allodial proprietors of land were told that they must surrender it to the king, and take back — not merely “some,” but — the whole of it, under some certain provisions, which, it was said, would procure a valuable object — the very object was security — security for their property. What was the result? They received their land back again, indeed; but they received it, loaded with all the oppressive burthens of the feudal servitude — cruel, indeed; so far as the epithet cruel can be applied to matters merely of property.”

Wilson contends that rights exist without tradition or government. Rather than create those rights, a “wise and good” government ensures their total protection:

“In a state of natural liberty, every one is allowed to act according to his own inclination, provided he transgress not those limits, which are assigned to him by the law of nature: in a state of civil liberty, he is allowed to act according to his inclination, provided he transgress not those limits, which are assigned to him by the municipal law. True it is, that, by the municipal law, some things may be prohibited, which are not prohibited by the law of nature: but equally true it is, that, under a government which is wise and good, every citizen will gain more liberty than he can lose by these prohibitions. He will gain more by the limitation of other men’s freedom, than he can lose by the diminution of his own. He will gain more by the enlarged and undisturbed exercise of his natural liberty in innumerable instances, than he can lose by the restriction of it in a few.”

In contrast, he takes Burke’s view of rights to its natural conclusion.

“man is not only made for, but made by the government: he is nothing but what the society frames: he can claim nothing but what the society provides. His natural state and his natural rights are withdrawn altogether from notice.”

He writes further that “rights result from the natural state of man; from that situation, in which he would find himself, if no civil government was instituted.”

In other words, government does not need to exist for men to assert their rights. Property rights exist irrespective of governance.

Wilson concludes the essay by noting that in many ancient societies, including Rome and Greece, infanticide was a legally permitted practice on those considered weak or infirm.

However, among the tribal Germanic, labeled “barbarians” due to their lack of civil order, killing infants was considered “a most flagitious crime.” Paraphrasing the Roman historian Tacitus, Wilson observes that “good manners have more power, than good laws have over other nations. This shows that, in his time, the restraints of law began to be imposed on this unnatural practice; but that its inveteracy had rendered them still inefficacious.”

Put differently, the rights of those infants were recognized, despite the lack of a civil order.

Whether those specific historical claims are true or not, Wilson’s point remains. An infant, or an adult for that matter, has a right to live whether the land they’re on at the moment is in a “civil order.”

The implications are also clear of Burke’s beliefs: if a government bestows rights, then it can take them away, and man exists for the government rather than the other way around.

One can believe this, as Burke did. But it raises the question of how Burke could also argue that men can give up liberties to secure others if those freedoms are not theirs to give in the first place.

As Wilson put it, “a man has a natural right to his property, to his character, to liberty, and to safety.”

TJ Martinell

TJ Martinell is an author, writer, and award-winning reporter from Washington state. His dystopian novel The Stringers depicting a neo-Prohibition Era in the city of Seattle is available on Amazon.