A banner hanging at a house across Wyckoff Hospital in Bushwick honoring first responders. (Erik McGregor/LightRocket via Getty Images)

‘A Year Ago I Was a Hero. Now I’m Treated Like Scum.’ – Frontline workers are choosing to lose their jobs rather than get the vaccine. Why?

By Suzy Weiss

At the outset of the pandemic, Becca Pitts, a 21-year-old certified nursing assistant from Crawfordsville, Ind., worked 60-hour weeks, doing 12- and sometimes 16-hour shifts in nursing homes and hospital wards helping patients shower and eat. She had to wear the same surgical mask for up to a week because of shortages. She was emotionally drained. She didn’t always have a surgical gown.

Pitts says that, in those early days, “You would have no idea what you were walking into.” Some weeks, she’d work evening shifts until eleven o’clock. Other times, she’d wake up at four a.m. to drive the two hours to make it to the hospital for the early shift.

For this work, she was hailed as a superhero. During the holidays last year, office personnel doled out goodie bags. Another facility she worked for held raffles for televisions and top-of-the-line microwaves. And they gave out cash prizes to employees—just for showing up.

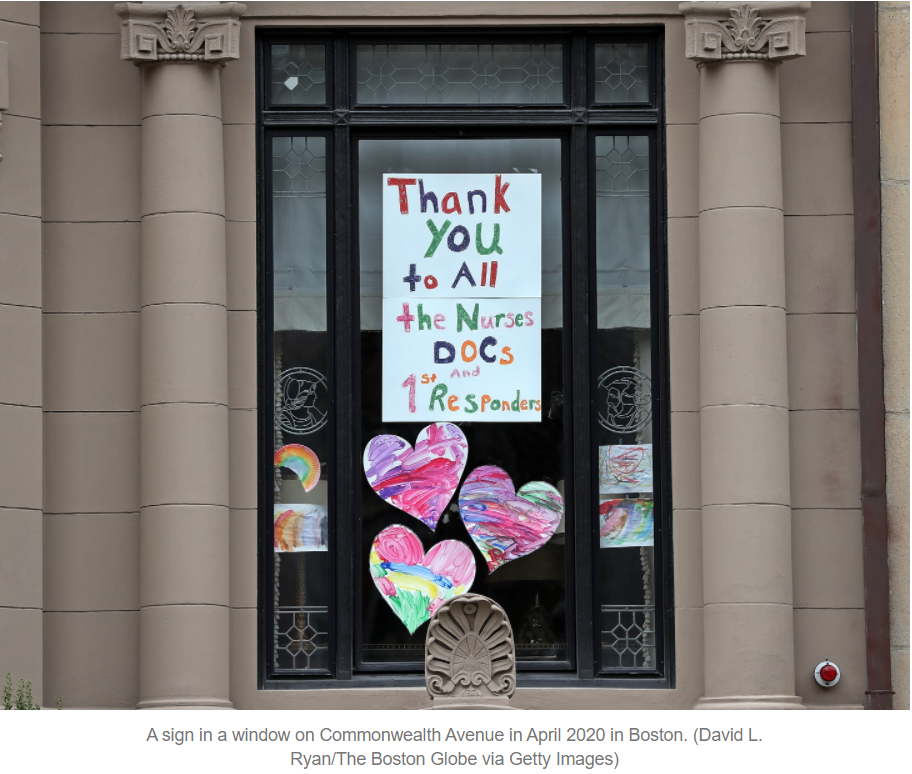

“Our administrators threw us pizza parties and doughnut parties constantly,” Pitts says. She says all of the facilities she worked in were plastered with signs like “Heroes work here” and “Thank you for your service” and that local residents would sometimes cheer for her and her coworkers when they emerged after a long shift. When Pitts’s family heard she was exhausted and feeling down, they wrote her thank you cards. They told her they were proud of her.

Now, those same family members say they don’t want to be around Pitts at all. “A year ago I was a hero, and now I’m being treated like scum,” she says.

That’s because Pitts refuses to get vaccinated. “I’m only 21, I want to have a family in the next three years, and we don’t know the long-term side effects,” she tells me when I ask her why. Not only has Pitts become a pariah in her own family—she and her six-year-old sister are the only ones without the vaccine—but, with a wave of mandates being issued by federal and state officials, she faces termination if she doesn’t get her first shot by the end of this month.

Pitts is not alone. While vaccine mandates sweep the country, frontline workers who are refusing the shot are being recast as villains. And there are a lot of villains. According to the Covid States Project, 23% of healthcare workers are unvaccinated. About 40% of Ohio’s nursing home workers remain unvaccinated. In New York City, 9,000 municipal workers have been placed on unpaid leave, plus 12,000 more who have yet to get the vaccine, but are allowed to keep working while the city evaluates their exemption requests.

The same thing that won them praise last year—their willingness to keep working, enveloped by tons of other people—is now a liability for firefighters, healthcare workers and teachers whose unwillingness to play by the rules is seen as selfish and a public-health hazard.

There’s also a sense that, when it comes to frontline workers, they should just know better. If we can’t trust them to take care of themselves, the thinking goes, how can we trust them to teach our kids, put out fires, or care for us when we are sick? If they exhibit such poor judgment on this score, why should we trust their judgment on anything else? How could they let politics get in the way of doing the right thing?

A sign in a window on Commonwealth Avenue in April 2020 in Boston. (David L. Ryan/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

This has confused and angered many frontline workers. They argue that it’s not their decision to opt out that’s political and divisive—it’s the mandates themselves.

“I looked down at my old badge,” says Jen Peters, 39, a San Diego-based maternity nurse turned private lactation consultant. “They had given us all a clip during Covid that said my hospital’s name and ‘Stronger Together.’ I thought, ‘My, how times have changed.’”

The California-wide mandate came out in August, and Peters, who had given birth to a baby girl five months prior, applied for an exemption because she was worried about how the vaccine might affect her breast milk. She was denied. On her last day, October 28, her coworkers brought in cupcakes; a fellow nurse gave her a bouquet of white lilies and yellow roses. “People came up to me that day and said, ‘You know what, I’m vaccinated, and we really wish you would do this to stay with us,’” Peters told me.

The pro-mandate camp insists the mandates are commonsensical. In New York City, for example, the city-wide mandate appears to have prompted 18,000 public school employees to get the vaccine, bumping the inoculation rate up to 95 percent. But to Garen Pido, an unvaccinated nurse in Ventura, Calif., they’re “punitive.”

Pido, and the other frontline workers I spoke to, mostly questioned the science: the new mRNA technology in the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines; the speed with which the FDA approved those vaccines; fears about infertility and side effects. All this despite the fact that 96 percent of doctors, who know a thing or two about science, had been fully vaccinated by June.

Some pointed out the absurdity of being forced to get a vaccine when they had already recovered from Covid and therefore had natural immunity to the virus. (The largest Covid study worldwide, which was conducted in Israel, showed that natural immunity was 27 times more effective than vaccinated immunity in preventing Covid infection.)

But above all, they hated that someone was telling them what they had to do.

They told me that maintaining bodily autonomy was tantamount to freedom. Not getting the vaccine, in the eyes of these frontline workers, was a way of asserting control over their destiny. It was a way of saying to the state and their bosses and all the bureaucrats and influencers and corporations: you may have more power, but I am not powerless. Ricky, a paramedic in California who didn’t want his last name in print, put it this way: “Now that I’m being fired for not listening to my ambulance company, I’m in a position of, ‘I’m not doing anything you want me to do. I’m going to dig my heels in even harder.”

Some states are filing lawsuits to block the mandates that are putting frontline workers like Ricky and Pitts and Peters out of work. Indiana’s attorney general announced a lawsuit earlier this month pushing back against the federal mandate—it’s the third of its kind—in conjunction with Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Idaho, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Utah and West Virginia. Unions are also filing suit, as in Los Angeles, or cutting deals with city officials, as in New York, to get workers more time to file exemptions or more benefits if they go on leave. But as more and more (and younger and younger) people get vaccinated, “no jab, no job” looks inevitable.

“It grinds my gears that health has been politicized,” says Fracisco Gomez, 28, a paraprofessional with the NYC Department of Education. “They say that I’m a Donald Trump fan, a MAGA-supporter, or that I don’t believe science and I listen to QAnon.” Gomez, who lives in the South Bronx, is a registered Democrat and former de Blasio intern in the Office of Immigrant Affairs. “We’re not all psycho Republicans,” he adds.

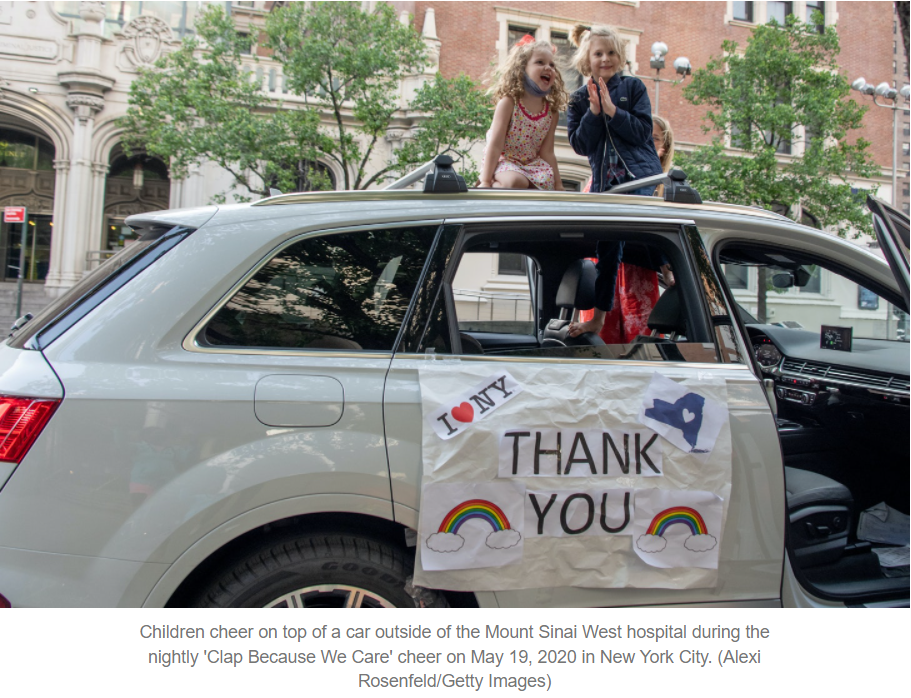

Children cheer on top of a car outside of the Mount Sinai West hospital during the nightly ‘Clap Because We Care’ cheer on May 19, 2020 in New York City. (Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty Images)

Gomez has spent the past five years helping kids with autism and other disabilities at a public school in New York City. On the Wednesday before the mandate kicked in he called his union representative, who said that the union couldn’t help him and that he didn’t qualify for a pension. After hanging up, Gomez walked into the assistant principal’s office and said he felt used. “I was working in the building for the entire pandemic,” he said. Gomez walked out, wept, and then went on voluntary leave. (Though he stopped getting paid in mid-October, he says he still gets benefits like healthcare.)

“I was just getting a round of applause for being an essential worker,” says Gomez, who lives with his mother and grandmother, both of whom have the vaccine. “Now, four or five months later, I’m being thrown under the bus.” I asked him whether he’s worried about getting his family sick. “At this point, they’re a little more worried about me than themselves.”

Gomez recalled that, at the height of the pandemic, he had to be quarantined twice, when he was exposed to Covid by his students. He didn’t like it when less experienced substitutes were paid $200 a day to do his job—about twice what he makes after taxes. I asked him why he didn’t just get vaccinated—if not for the sake of the students and the mandate but for his own health. Why derail his career? “What made me not want to take it is because they were forcing me to take the vaccine or I lose my job,” he says.

Until recently, Ricky’s husband, Alex, was a teacher at a charter school in southern California. But he resigned last month after refusing to get vaccinated. He said he didn’t feel he needed it given his risk profile and told me that the policies around Covid in his school and beyond were confusing and contradictory throughout the pandemic. “We’ve been tossed to and fro throughout the entire pandemic. We’re told that our jobs are so valuable and that we’re heroes, but come this month, we’re being told we’re the enemy. That we’re murderers, and just like drunk drivers.”

An exodus of frontline workers who are refusing the vaccine threatens to exacerbate labor shortages nationwide.

Pitts, the nurse in Indiana, says the pandemic has left many nurses burned out. “I worked in a building recently where it was me and a nurse to 62 patients, and I worked another hallway where I was the only aid,” she says. “Usually, it’s two or three.” Pitts was planning to go to nursing school next year, but, after she learned she’d have to get vaccinated, she decided she’d get a job in retail or, maybe, waiting tables during the holidays.

Garen Pido, the nurse in California, says she gets texts every day to come pick up overtime shifts. Her husband, a firefighter, who is hoping that the deadline to get the vaccine will be pushed back (as it has in previous months), says the firehouse is “insanely busy, and so short on staff.” He thinks the vaccine mandate—along with aging firefighters retiring and recruitment having taken a hit during the pandemic—will be a big problem. “Los Angeles doesn’t know what’s about to hit them,” he says.

Ricky said that he and Alex are thinking about moving to a state more friendly to anti-vaxxers. “We’re looking at Tennessee and Kentucky and the Carolinas,” Ricky said.

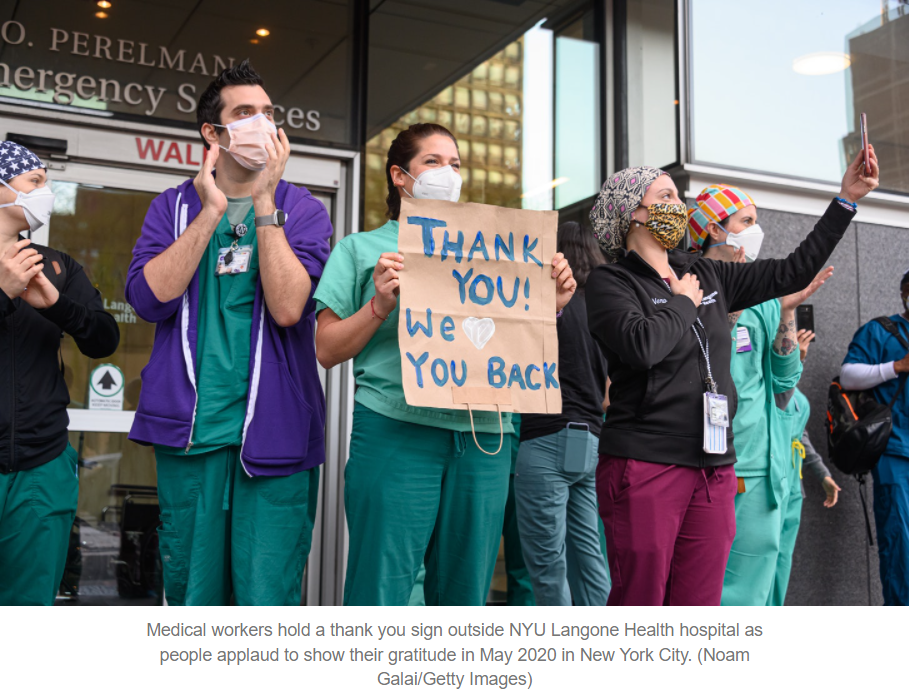

Medical workers hold a thank you sign outside NYU Langone Health hospital as people applaud to show their gratitude in May 2020 in New York City. (Noam Galai/Getty Images)

Unlike most former frontline workers, Gomez seems to have embraced his new life. Since going on leave, he’s read Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick” and a slew of personal-finance, D.I.Y. books like “Rich Dad Poor Dad” and “Think and Grow Rich.” He’s now trading cryptocurrency and stocks, and minting non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, which he sells for cash.

Still, he misses getting out of the house and going to work. “I’ll probably get it after New Year’s,” Gomez says of the vaccine. “Literally, when I’m at my last dollar, and I’m starving. Then I’ll go back to living poor instead of living in poverty.”

After a pause, he says: “They want everyone to get in line for economic and political reasons. FGomwF I see the vaccine as a symbol of all of that.”

Suzy’s last piece for us was about America’s baby bust. Read it here.

And, in case you missed it, our most recent podcast was a conversation with Dr. Marty Makary about all things Covid:

A banner hanging at a house across Wyckoff Hospital in Bushwick honoring first responders. (Erik McGregor/LightRocket via Getty Images)

At the outset of the pandemic, Becca Pitts, a 21-year-old certified nursing assistant from Crawfordsville, Ind., worked 60-hour weeks, doing 12- and sometimes 16-hour shifts in nursing homes and hospital wards helping patients shower and eat. She had to wear the same surgical mask for up to a week because of shortages. She was emotionally drained. She didn’t always have a surgical gown.

Pitts says that, in those early days, “You would have no idea what you were walking into.” Some weeks, she’d work evening shifts until eleven o’clock. Other times, she’d wake up at four a.m. to drive the two hours to make it to the hospital for the early shift.

For this work, she was hailed as a superhero. During the holidays last year, office personnel doled out goodie bags. Another facility she worked for held raffles for televisions and top-of-the-line microwaves. And they gave out cash prizes to employees—just for showing up.

“Our administrators threw us pizza parties and doughnut parties constantly,” Pitts says. She says all of the facilities she worked in were plastered with signs like “Heroes work here” and “Thank you for your service” and that local residents would sometimes cheer for her and her coworkers when they emerged after a long shift. When Pitts’s family heard she was exhausted and feeling down, they wrote her thank you cards. They told her they were proud of her.

Now, those same family members say they don’t want to be around Pitts at all. “A year ago I was a hero, and now I’m being treated like scum,” she says.

That’s because Pitts refuses to get vaccinated. “I’m only 21, I want to have a family in the next three years, and we don’t know the long-term side effects,” she tells me when I ask her why. Not only has Pitts become a pariah in her own family—she and her six-year-old sister are the only ones without the vaccine—but, with a wave of mandates being issued by federal and state officials, she faces termination if she doesn’t get her first shot by the end of this month.

Pitts is not alone. While vaccine mandates sweep the country, frontline workers who are refusing the shot are being recast as villains. And there are a lot of villains. According to the Covid States Project, 23% of healthcare workers are unvaccinated. About 40% of Ohio’s nursing home workers remain unvaccinated. In New York City, 9,000 municipal workers have been placed on unpaid leave, plus 12,000 more who have yet to get the vaccine, but are allowed to keep working while the city evaluates their exemption requests.

The same thing that won them praise last year—their willingness to keep working, enveloped by tons of other people—is now a liability for firefighters, healthcare workers and teachers whose unwillingness to play by the rules is seen as selfish and a public-health hazard.

There’s also a sense that, when it comes to frontline workers, they should just know better. If we can’t trust them to take care of themselves, the thinking goes, how can we trust them to teach our kids, put out fires, or care for us when we are sick? If they exhibit such poor judgment on this score, why should we trust their judgment on anything else? How could they let politics get in the way of doing the right thing?

A sign in a window on Commonwealth Avenue in April 2020 in Boston. (David L. Ryan/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

This has confused and angered many frontline workers. They argue that it’s not their decision to opt out that’s political and divisive—it’s the mandates themselves.

“I looked down at my old badge,” says Jen Peters, 39, a San Diego-based maternity nurse turned private lactation consultant. “They had given us all a clip during Covid that said my hospital’s name and ‘Stronger Together.’ I thought, ‘My, how times have changed.’”

The California-wide mandate came out in August, and Peters, who had given birth to a baby girl five months prior, applied for an exemption because she was worried about how the vaccine might affect her breast milk. She was denied. On her last day, October 28, her coworkers brought in cupcakes; a fellow nurse gave her a bouquet of white lilies and yellow roses. “People came up to me that day and said, ‘You know what, I’m vaccinated, and we really wish you would do this to stay with us,’” Peters told me.

The pro-mandate camp insists the mandates are commonsensical. In New York City, for example, the city-wide mandate appears to have prompted 18,000 public school employees to get the vaccine, bumping the inoculation rate up to 95 percent. But to Garen Pido, an unvaccinated nurse in Ventura, Calif., they’re “punitive.”

Pido, and the other frontline workers I spoke to, mostly questioned the science: the new mRNA technology in the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines; the speed with which the FDA approved those vaccines; fears about infertility and side effects. All this despite the fact that 96 percent of doctors, who know a thing or two about science, had been fully vaccinated by June.

Some pointed out the absurdity of being forced to get a vaccine when they had already recovered from Covid and therefore had natural immunity to the virus. (The largest Covid study worldwide, which was conducted in Israel, showed that natural immunity was 27 times more effective than vaccinated immunity in preventing Covid infection.)

But above all, they hated that someone was telling them what they had to do.

They told me that maintaining bodily autonomy was tantamount to freedom. Not getting the vaccine, in the eyes of these frontline workers, was a way of asserting control over their destiny. It was a way of saying to the state and their bosses and all the bureaucrats and influencers and corporations: you may have more power, but I am not powerless. Ricky, a paramedic in California who didn’t want his last name in print, put it this way: “Now that I’m being fired for not listening to my ambulance company, I’m in a position of, ‘I’m not doing anything you want me to do. I’m going to dig my heels in even harder.”

Some states are filing lawsuits to block the mandates that are putting frontline workers like Ricky and Pitts and Peters out of work. Indiana’s attorney general announced a lawsuit earlier this month pushing back against the federal mandate—it’s the third of its kind—in conjunction with Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Idaho, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Utah and West Virginia. Unions are also filing suit, as in Los Angeles, or cutting deals with city officials, as in New York, to get workers more time to file exemptions or more benefits if they go on leave. But as more and more (and younger and younger) people get vaccinated, “no jab, no job” looks inevitable.

“It grinds my gears that health has been politicized,” says Fracisco Gomez, 28, a paraprofessional with the NYC Department of Education. “They say that I’m a Donald Trump fan, a MAGA-supporter, or that I don’t believe science and I listen to QAnon.” Gomez, who lives in the South Bronx, is a registered Democrat and former de Blasio intern in the Office of Immigrant Affairs. “We’re not all psycho Republicans,” he adds.

Children cheer on top of a car outside of the Mount Sinai West hospital during the nightly ‘Clap Because We Care’ cheer on May 19, 2020 in New York City. (Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty Images)

Gomez has spent the past five years helping kids with autism and other disabilities at a public school in New York City. On the Wednesday before the mandate kicked in he called his union representative, who said that the union couldn’t help him and that he didn’t qualify for a pension. After hanging up, Gomez walked into the assistant principal’s office and said he felt used. “I was working in the building for the entire pandemic,” he said. Gomez walked out, wept, and then went on voluntary leave. (Though he stopped getting paid in mid-October, he says he still gets benefits like healthcare.)

“I was just getting a round of applause for being an essential worker,” says Gomez, who lives with his mother and grandmother, both of whom have the vaccine. “Now, four or five months later, I’m being thrown under the bus.” I asked him whether he’s worried about getting his family sick. “At this point, they’re a little more worried about me than themselves.”

Gomez recalled that, at the height of the pandemic, he had to be quarantined twice, when he was exposed to Covid by his students. He didn’t like it when less experienced substitutes were paid $200 a day to do his job—about twice what he makes after taxes. I asked him why he didn’t just get vaccinated—if not for the sake of the students and the mandate but for his own health? Why derail his career? “What made me not want to take it is because they were forcing me to take the vaccine or I lose my job,” he says.

Until recently, Ricky’s husband, Alex, was a teacher at a charter school in southern California. But he resigned last month after refusing to get vaccinated. He said he didn’t feel he needed it given his risk profile and told me that the policies around Covid in his school and beyond were confusing and contradictory throughout the pandemic. “We’ve been tossed to and fro throughout the entire pandemic. We’re told that our jobs are so valuable and that we’re heroes, but come this month, we’re being told we’re the enemy. That we’re murderers, and just like drunk drivers.”

An exodus of frontline workers who are refusing the vaccine threatens to exacerbate labor shortages nationwide.

Pitts, the nurse in Indiana, says the pandemic has left many nurses burned out. “I worked in a building recently where it was me and a nurse to 62 patients, and I worked another hallway where I was the only aid,” she says. “Usually, it’s two or three.” Pitts was planning to go to nursing school next year, but, after she learned she’d have to get vaccinated, she decided she’d get a job in retail or, maybe, waiting tables during the holidays.

Garen Pido, the nurse in California, says she gets texts every day to come pick up overtime shifts. Her husband, a firefighter, who is hoping that the deadline to get the vaccine will be pushed back (as it has in previous months), says the firehouse is “insanely busy, and so short on staff.” He thinks the vaccine mandate—along with aging firefighters retiring and recruitment having taken a hit during the pandemic—will be a big problem. “Los Angeles doesn’t know what’s about to hit them,” he says.

Ricky said that he and Alex are thinking about moving to a state more friendly to anti-vaxxers. “We’re looking at Tennessee and Kentucky and the Carolinas,” Ricky said.

Medical workers hold a thank you sign outside NYU Langone Health hospital as people applaud to show their gratitude in May 2020 in New York City. (Noam Galai/Getty Images)

Unlike most former frontline workers, Gomez seems to have embraced his new life. Since going on leave, he’s read Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick” and a slew of personal-finance, D.I.Y. books like “Rich Dad Poor Dad” and “Think and Grow Rich.” He’s now trading cryptocurrency and stocks, and minting non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, which he sells for cash.

Still, he misses getting out of the house and going to work. “I’ll probably get it after New Year’s,” Gomez says of the vaccine. “Literally, when I’m at my last dollar, and I’m starving. Then I’ll go back to living poor instead of living in poverty.”

After a pause, he says: “They want everyone to get in line for economic and political reasons. If America really cared about our health we would have universal health care. But really they just care about us moving forward as cogs. I see the vaccine as a symbol of all of that.”

Suzy’s last piece for us was about America’s baby bust. Read it here.

And, in case you missed it, our most recent podcast was a conversation with Dr. Marty Makary about all things Covid: