Weather made (sort of) understandable: Part One

By Dr. Jay Lehr, Terigi Ciccone

We shall start at the beginning with possibly a shocking exclamation. Weather is nothing more and nothing less than nature trying to equilibrate the balance of all energy transmitted to the Earth by the sun. It is a never ending multilevel show of physics trying to overcome imbalances and irregularities too numerous to accurately quantify and yet we try hour after hour day after day all across the Earth.

Climate is simply the trends of weather over a long period. We never stop talking about it. It’s too hot. It’s too cold. I’m tired of the rain. I wish this spring would last forever. Don’t worry, there’s plenty of snow at the top of the mountain. This is the weather. We talk about it, we complain about it, we wish about it, but nobody can do anything about it.

With the help of technology in recent decades, like satellites, Doppler radar, telemetry, etc., we are getting pretty good at predicting how the weather is most likely to change over the next SEVERAL days. In Florida and Hawaii, it’s so easy, we don’t even need weather persons. At other locations, say, near tall mountains or along the coastlines, predicting the weather is harder, and forecasts are less reliable.

THE WIND

Wind is simply the movement of air. Its action is caused by temperature differences and atmospheric pressure differences from one place to another. Some differences are the result of the sun heating the earth in one area and not another. It also happens where a portion of the land that’s heated is a mountain, and another part is a valley. Along the coast, the earth is warmed faster than the ocean or if half of the sky is cloudy and half is not. Warm air is lighter than cold air, so it climbs into the sky, and then colder air rushes in to fill the void created by the warm air rising. Nature doesn’t like imbalances of any kind.

Wind is simply the movement of air. Its action is caused by temperature differences and atmospheric pressure differences from one place to another. Some differences are the result of the sun heating the earth in one area and not another. It also happens where a portion of the land that’s heated is a mountain, and another part is a valley. Along the coast, the earth is warmed faster than the ocean or if half of the sky is cloudy and half is not. Warm air is lighter than cold air, so it climbs into the sky, and then colder air rushes in to fill the void created by the warm air rising. Nature doesn’t like imbalances of any kind.

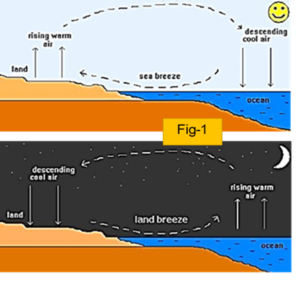

Near a warm and sunny beach in the early afternoon, we will get a gentle, cooling summer breeze coming in from the ocean to replace the rising warm air which heated up faster than the water. As shown in Fig 1 at night, the process generally reverses, because the water is now warmer than the land.

At other locations and circumstances, it can be a wild ride, like a jet stream. These are fast-moving rivers of air at the boundaries of massive weather fronts. Here one is hot and the other cold. They flow west to east in the opposite direction in response to the sun’s warming rotation from east to west. At the jet stream core, which is about ten to fifteen kilometers high, the airspeeds can reach several hundreds of miles per hour and move in serpentine paths over continents. These fast-moving core winds drag the adjacent air, forming a velocity gradient that’s very -very fast near the center and keeps slowing down and down until it reaches near-zero speeds some hundreds of Kilometers away. Naturally, if mountains or tall buildings get in the way, the wind changes directions and speed in many turbulent and unpredictable ways.

BAROMETRIC PRESSURE

This is the weight of the volume of air on top of you. At sunrise, if you are at the beach at sea level, and the temperature is 15° C, (69 F) there’s a column of air on top of you going all the way up into outer space. The weight of that air pressing down on you has a force of about 14.7 PSI (pounds per square inch) on your body. If you then go to the rooftop restaurant for brunch at 250 feet high, the pressure on you decreases from 14.7 to 14.3 PSI. Meanwhile, if you have a friend, who is mountain climbing at 2,400 feet, the pressure on him is only about 10.9 PSI. Now the heaviest air, meaning the densest air, is at sea level, and as we go up, it progressively gets less and less dense until near outer space, it’s about zero PSI. Figure 2 illustrators the impact of changing atmospheric pressure on a sealed bottle of water moving from 14,000 feet elevation down to 1000 feet.

This is the weight of the volume of air on top of you. At sunrise, if you are at the beach at sea level, and the temperature is 15° C, (69 F) there’s a column of air on top of you going all the way up into outer space. The weight of that air pressing down on you has a force of about 14.7 PSI (pounds per square inch) on your body. If you then go to the rooftop restaurant for brunch at 250 feet high, the pressure on you decreases from 14.7 to 14.3 PSI. Meanwhile, if you have a friend, who is mountain climbing at 2,400 feet, the pressure on him is only about 10.9 PSI. Now the heaviest air, meaning the densest air, is at sea level, and as we go up, it progressively gets less and less dense until near outer space, it’s about zero PSI. Figure 2 illustrators the impact of changing atmospheric pressure on a sealed bottle of water moving from 14,000 feet elevation down to 1000 feet.

BAROMETRIC PRESSURE AND TEMPERATURE RELATIONSHIP

Back at the beach the sun has been warming it up for about five hours. It’s the hottest time of the day when the sun is directly overhead, about noon. Now you might say, “But wait. Why does it usually feel warmer an hour or two into the afternoon, when the sun is no longer at its highest position (called the apex). That’s because an hour or two after the apex, while you’re getting a little less energy from the sun on your head, the earth you are standing on has already been heated by the sun and some of that stored heat in the ground starts radiating and convecting up to you. You are now heated on the top by the sun and from the bottom by the warm ground.

If you are a football fan you will remember Deflate-Gate where Tom Brady was accused of deflating footballs to his liking. Maybe he didn’t. It was noon at Indianapolis’ Lucas Oil Stadium, and the footballs are brought to the field for practice and then for play. The balls came out of a toasty locker room at 75° (Fahrenheit), and the footballs and the air inside the footballs are also at 75° F, and the PSI is 13.0. Where the NFL likes them. But on the playing field, it’s a chilly 25° F. The footballs and the air inside starts to immediately cool down until the balls, and the air inside, reach 25° F. The question is – what’s happened to the balls? The simple answer is that the pressure in the balls decreased to 11 PSI the way Brady likes them.

BAROMETRIC PRESSURE AND SPECIFIC VOLUME

Let’s now put together these three measures, pressure, temperature, and volume and see how they generate wind. If we decrease the air temperature, the air density will increase, and the volume will decrease. Alternatively, if we reduce the pressure, the air volume will increase, and temperature will rise. So, we will need to specify two of these variables to see what it does to the third. But, you may ask, if hot air rises, why is it colder at the top of the mountain than at the base? The answer is that on top of the mountain, the air is less dense because of the lower barometric pressure. Another example of this relationship is that at sea level, water boils/turns to steam at 100° C. But if you are at the top of Mount Kilimanjaro at 20,000 feet, it will start boiling at 81° C. Or if you’re below sea level, like in parts of Death Valley California, the boiling point is about 103° C.

THE WEATHER VEHICLE

We have laid out our crazy cartoon model weather machine, in Fig 3. The sun is the engine, and it provides nearly 100 percent of the power to drive it, which we’ll call “temperature.” The transmission, is the way, the heat from the sun is distributed geographically in one part of the world and not in the other. It’s like a transmission that sends different speeds to each wheel, resulting in erratic motion. We’ll call this “specific volume.”

We have laid out our crazy cartoon model weather machine, in Fig 3. The sun is the engine, and it provides nearly 100 percent of the power to drive it, which we’ll call “temperature.” The transmission, is the way, the heat from the sun is distributed geographically in one part of the world and not in the other. It’s like a transmission that sends different speeds to each wheel, resulting in erratic motion. We’ll call this “specific volume.”

We then have barometric pressure, which regulates how much air enters the engine. Does it all seem if not crazy, awfully complex? That is because it is.

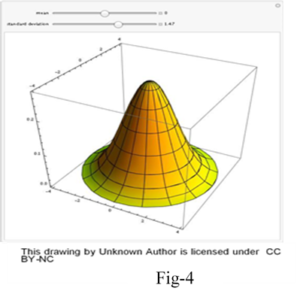

How does the earth receive the sun’s energy? Let’s turn on the engine and see what happens. We have sunlight arriving on the planet and spreading out like a three-dimensional bell curve as shown in Fig 4. The top-center of the bell is precisely on the equator, and it’s at the highest point on  the bell. That means that the energy density there is the maximum. At the bottom of the bell are the north and south Polar Regions. The amount of energy received from the sun is almost the same, but it’s now spread over a vastly larger area.

the bell. That means that the energy density there is the maximum. At the bottom of the bell are the north and south Polar Regions. The amount of energy received from the sun is almost the same, but it’s now spread over a vastly larger area.

On earth, where we have land, oceans, and air, they are all set in motion to eliminate these temperature and pressure imbalances. It does so in the atmosphere primarily by the wind. In the seas by water movements like the Gulf Stream in the Atlantic and in the Pacific with the “Pacific Oscillator” and “El Niño Nino/La Niña. On land, it does it primarily by radiation, convection mostly to the air. On the earth, some of this heat is also conducted deeper in the ground, which is essential for plants to grow. It warms up and dries out the soil in the spring, allowing plant roots to grow. Some of the heat in the warmed earth is radiated and convected back up into the air, creating vertical wind streams that help gliders fly around without engines, and birds without flapping their wings.

But along the way, the winds have to overcome many obstacles posed by obstructions like mountain ranges and narrow canyons, plus human-made buildings and cars, trucks, planes, and wind turbines. In rare cases, it can also be caused independently of the effects of the sun. For example, the low temperatures mass of the Antarctic ice will always be much colder than the sea and air temperatures of the southern temperate regions. Thus, like the jet stream in the north, it forms a planetary sub-weather system, which we call a “polar vortex.”

As you learn more about weather it will become clear to you how preposterous it is that people think they can predict and control weather a century from now

In Part two of this series we will discuss fascinating variations in weather as it relates to places and mediums.

Authors

Dr. Jay Lehr

CFACT Senior Science Analyst Jay Lehr has authored more than 1,000 magazine and journal articles and 36 books. Jay’s new book A Hitchhikers Journey Through Climate Change written with Teri Ciccone is now available on Kindle and Amazon.

Terigi Ciccone

Engineer, Science Enthusiast and Artist. Loves reading and travel, Naturalist, Author of the new book “A Hitchhiker’s Journey Through Climate Change.”

From cfact.org