Hunter Hollingsworth’s story contains alarming claims regarding the behavior of government officials and raises a bevy of questions over Open Fields, states’ rights, and the sanctity of private property.

(Photo courtesy of Institute for Justice)

Government Cameras Hidden on Private Property? Welcome to Open Fields

Seated at his kitchen table, finishing off the remains of a Saturday breakfast, Hunter Hollingsworth’s world was rocked by footsteps on his front porch and pounding at the door, punctuated by an aggressive order: “Open up or we’ll kick the door down.”

Surrounded on all sides of his house, and the driveway blocked, Hollingsworth was the target of approximately 10 federal and state wildlife officials packing pistols, shotguns and rifles. And what was Hollingsworth’s crime? Drugs, armed robbery, assault, money laundering? Not quite.

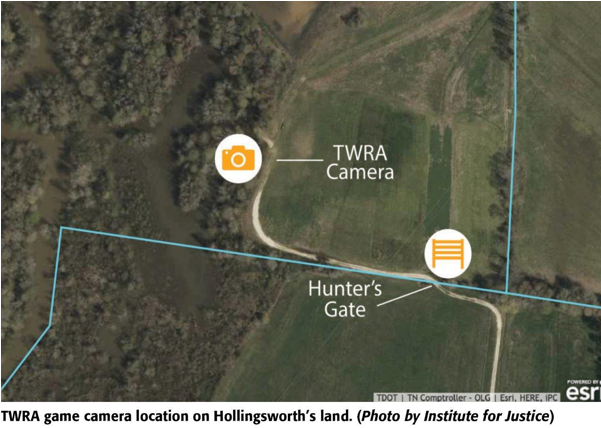

Months prior, in 2018, the Tennessee landowner removed a game camera secretly strapped to a tree on his private land by wildlife officials in order to monitor his activity without apparent sanction or probable cause. Repeat: Hollingsworth’s residence was searched by U.S. government and state officials, dressed to the nines in assault gear, seeking to regain possession of a trail camera—the precise camera they had surreptitiously placed on his private acreage after sneaking onto his property at night, loading the camera with active SD and SIM cards, and zip-tying the device roughly 10’ high up a tree—all without a warrant.

Can the government place cameras and monitoring equipment on a private citizen’s land at will, or conduct surveillance and stakeouts on private land, without probable cause or a search warrant? Indeed, according to the U.S. Supreme Court’s (SCOTUS) interpretation of the Fourth Amendment. Welcome to Open Fields.

The vast majority of Americans assume law enforcement needs a warrant to carry out surveillance, but for roughly a century, SCOTUS has ruled that private land—is not private. Fourth Amendment protections against “unreasonable searches and seizures” expressed in the Bill of Rights only apply to an individual’s immediate dwelling area, according to SCOTUS.

However, SCOTUS’ Open Fields doctrine has been bucked in Mississippi, Montana, New York, Oregon and Vermont through protections granted by state constitutions, and for many American landowners, the more they discover about Open Fields—the more questions they have regarding the bounds of government power.

In Tennessee, Hollingsworth and Terry Rainwaters, another landowner who discovered multiple trail cameras on his property placed by the state, are taking their cases to state court, claiming violations of the Tennessee State Constitution. The Rainwaters and Hollingsworth stories contain alarming claims regarding the behavior of wildlife officials and raise a bevy of questions over Open Fields, states’ rights, and the sanctity of private property.

Legal Stalking?

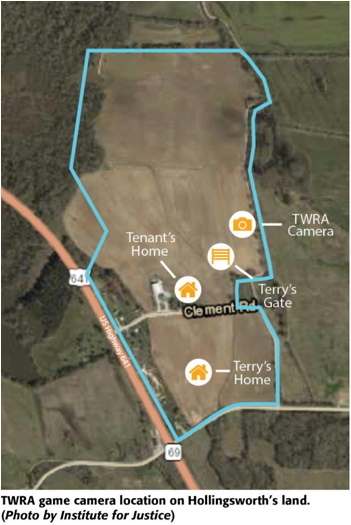

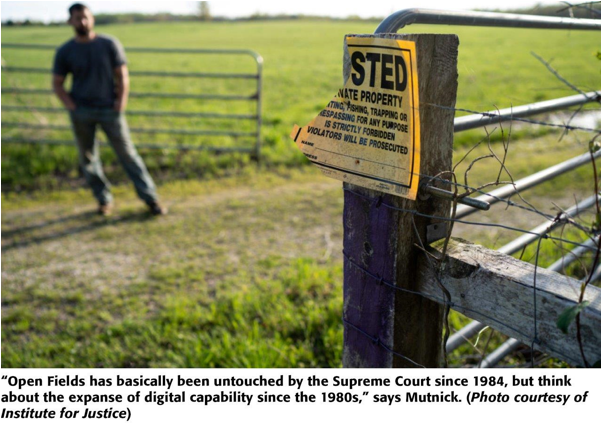

On bottomland squeezed in the rolling hills of northwest Tennessee’s Benton County, a short walk from the banks of the Big Sandy River, Terry Rainwaters, 53, owns 136 acres of land containing two homes, farmland and an equipment shed. Rainwaters and his son, Hunter Rainwaters, 20, live in one of the homes; a tenant occupies the other. The acreage is the physical center of Rainwaters’ life—a small place to farm, hunt and reside—with one way in, one way out, and a gate that stays locked, backed by “no trespassing” and “posted” signs.

On his way to hunt on his father’s land during the first week of December 2017, Hunter Rainwaters was driving a side-by-side through the property when he noticed an oddity positioned roughly 4’ off the ground. He popped the brakes, backed toward the object and looked in surprise at a trail camera belted to a tree.

“I didn’t see any words or stickers on it, but I knew right away it wasn’t ours,” Hunter Rainwaters recalls.

Following the hunt, he drove back onto the family property and spotted a second trail camera attached to a tree with several branches removed to allow for an unimpeded lens view. Rainwaters dialed his father’s cellphone, and described the two cameras: “I was shaken up when my son called and I knew immediately it had to be the TWRA (Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency),” Rainwaters recalls.

Deeply disturbed, Rainwaters arrived home later in the afternoon and took a look at the two cameras, mulling over whether to remove the pair. Two days later, with Rainwaters in limbo on what action to take—both cameras disappeared.

“Ask TWRA how many cameras they have on people’s private land right now watching their every move,” Rainwaters says. “I’ll bet they won’t answer that question and we all know why. No warrants, no judge, and no crime necessary, just set up surveillance and do whatever they want to.”

(Farm Journal asked TWRA multiple questions related to the use of trail cameras in surveilling Tennessee residents, including, but not limited to: Does TWRA have a list of past camera locations and current, active cameras? Who in TWRA is allowed to view the footage? How long are the cameras allowed to operate in place? Does TWRA recommend prosecution for a landowner for breaking or removing a camera? TWRA declined comment: “The Agency cannot comment on matters in litigation, nor can we provide comment on issues that are currently being litigated.” TWRA directed all questions to the Tennessee Attorney General’s office. However, the Tennessee AG office declined comment.)

“The cameras were collecting pictures of us hunting, driving and just our lives,” he adds. “One of the cameras was even recording footage up to the back of my tenant’s house.”

Rainwaters contends he has encountered armed TWRA agents on his private property on multiple occasions, either crossing his land or hiding in undergrowth during hunting season. Rainwaters explains: “TWRA officers sneak onto my land with no cause other than hoping to find somebody doing something wrong. I’ve got a clean hunting record and don’t look for trouble with nobody, but people just can’t believe what has happened on my land. It’s so wrong on so many levels and way past outrageous and dangerous. I don’t think people realize a ‘no trespassing’ sign or ‘private land’ sign mean nothing to the TWRA.”

Rainwaters contends he has encountered armed TWRA agents on his private property on multiple occasions, either crossing his land or hiding in undergrowth during hunting season. Rainwaters explains: “TWRA officers sneak onto my land with no cause other than hoping to find somebody doing something wrong. I’ve got a clean hunting record and don’t look for trouble with nobody, but people just can’t believe what has happened on my land. It’s so wrong on so many levels and way past outrageous and dangerous. I don’t think people realize a ‘no trespassing’ sign or ‘private land’ sign mean nothing to the TWRA.”

The alleged surveillance may have origins partially related to 2016 hunting violations, Rainwaters says, when his son and a group of friends were ticketed for baiting doves: “I paid their fines myself in what amounted to $380 times eight people. Yeah, all this started over hunting tickets and now TWRA thinks it’s OK to set up surveillance on my land.”

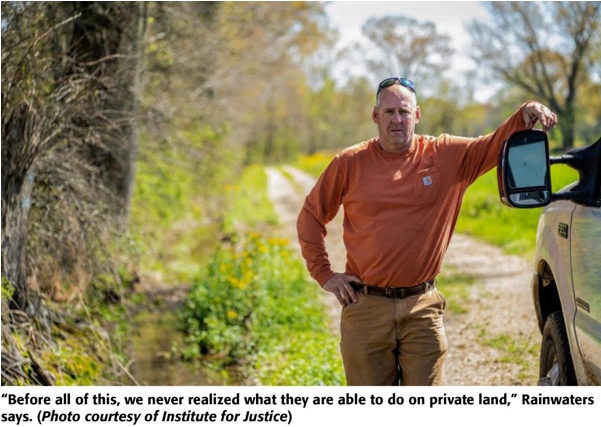

“Before all of this, we never realized what they are able to do on private land,” Rainwaters adds. “We’ve gotten so much response from people fired up over the TWRA, and most of them are like me, they’d never even heard of this ridiculous doctrine called Open Fields.”

Open Fields

The vast majority of Americans assume law enforcement needs a warrant to carry out surveillance, but for roughly a century, the U.S. Supreme Court (SCOTUS) has ruled that private land—is not so private. Fourth Amendment protections against “unreasonable searches and seizures” expressed in the Bill of Rights only apply to an individual’s immediate dwelling and curtilage, according to SCOTUS. Curtilage is an arcane term loosely translated as the area directly around a home, or the yard.

In 1924, Hester v. United States set up the Open Fields framework and said the U.S. Constitution does not extend to most land: “the special protection accorded by the Fourth Amendment to the people in their ‘persons, houses, papers, and effects,’ is not extended to the open fields.” Significantly, Open Fields is translated beyond its literal sense, and basically is defined as general acreage: woods, fields, farmland, barren ground, and more.

Further, in 1984, SCOTUS gave additional strength to Open Fields in Oliver v. United States: “open fields do not provide the setting for those intimate activities that the Amendment is intended to shelter from government interference or surveillance. There is no societal interest in protecting the privacy of those activities, such as the cultivation of crops that occur in open fields.”

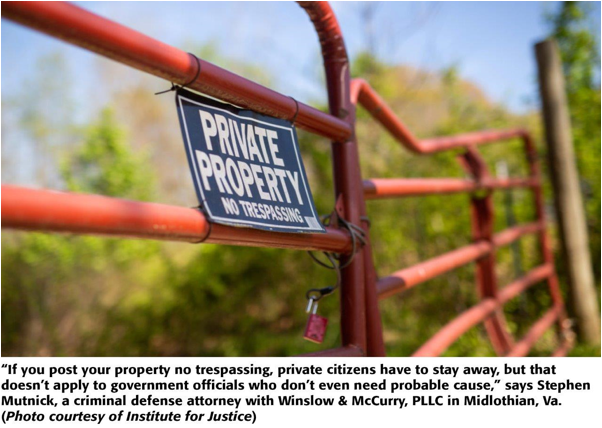

“I’m surprised we haven’t already heard more about Open Fields,” says Stephen Mutnick, a criminal defense attorney with Winslow & McCurry, PLLC in Midlothian, Va. “For right now, landowners have to remember that Fourth Amendment protections only extend to the home, personal effects and the curtilage. If you post your property no trespassing, private citizens have to stay away, but that doesn’t apply to government officials who don’t even need probable cause.”

However, SCOTUS’ Open Fields doctrine has been bucked in Mississippi, Montana, New York, Oregon and Vermont through protections granted by state constitutions. The Institute for Justice (IJ), a national libertarian law firm and legal advocacy group representing clients pro bono, has taken on both the Rainwaters and Hollingsworth cases. Tennessee could become the first state in 20 years to reject Open Fields.

“We got involved (Terry Rainwaters and Hunter Hollingsworth v. TWRA; Ed Carter; and Kevin Hoofman) in both cases because we see an egregious abuse of property and privacy rights under the Tennessee Constitution, and an opportunity to show why the federal Open Fields doctrine is so misguided,” says IJ attorney Joshua Windham.

(Farm Journal asked TWRA for its perspective on the Open Fields doctrine. TWRA declined comment: “The Agency cannot comment on matters in litigation, nor can we provide comment on issues that are currently being litigated.” TWRA directed all inquiries to the Tennessee Attorney General’s office. However, the Tennessee AG office did not respond to questions from Farm Journal.)

Windham insists private gates and “no trespassing” signs apply to government officials. “Otherwise the government is saying, ‘Your private land is my public property.’ Terry Rainwaters lives on his property, has a clean hunting record, yet he has to put up with wildlife officers hiding in bushes, ducking behind grass, and covertly recording his movements? By any definition, that is incredibly invasive,” Windham says.

“Everyone must keep in mind that the trail cameras were removed before Terry could take them down,” Windham continues. “That leaves at least two questions. One, how many pictures were taken? Two, how long were they going to keep taking them if Terry had never discovered the cameras?”

Windham’s questions rip the lid off a Pandora’s Box of additional queries. How often does TWRA place warrantless photo or video cameras on the land of state residents? Beyond the officer who places the camera, who else is in the know? Does TWRA have a list of past camera locations and current, active cameras? Who in government is allowed to view the footage? Who owns the footage? Is the government recording private/personal moments? Can the government film for days, weeks, years? Does TWRA recommend prosecution of a landowner for breaking or removing a camera? From both legal and ethical perspectives, the questions are extensive.

“Most people recognize that if the government can enter your land on a whim, and photograph you, or videotape you, without a warrant, that’s wrong on a basic level. But unfortunately, TWRA has been doing this for years and they’re still doing it today. What happened to Terry Rainwaters is not isolated—it’s widespread,” Windham says. “Look at Hunter Hollingsworth, for example. When people hear the details of what TWRA did on his land, they’re shocked.”

Secrets and Shadows

On ground that rubs the banks of the Big Sandy, roughly 5 miles as the crow flies from Terry Rainwaters’ farm, Hollingsworth owns 95 acres split between Henry and Benton counties. The acreage is remote, one road in and out, and gate access requires an easement access crossing two other landowners.

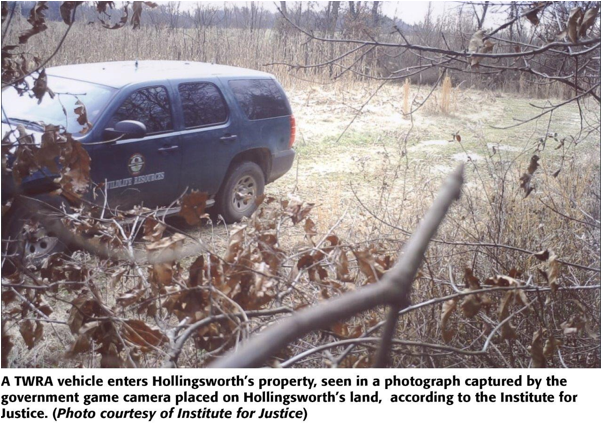

Approximately an hour before daylight on the morning of Jan. 26, 2018, Hollingsworth entered his property, intending to duck hunt, and as his truck rounded a curve, the headlights threw an unusual reflection high up a scrub oak—just enough light to spark Hollingsworth’s curiosity. Despite the likelihood of a raccoon or a forgotten piece of a rotting deer stand, he stopped the vehicle, walked toward the tree, and shined a flashlight up the trunk, illuminating the unexpected: a game camera and antenna zip-tied in place with the lens trained directly on his road and property.

Unnerved, Hollingsworth climbed into the tree, took note of several sawed limbs, cut the zip-ties, and removed the camera. Inside, he found an SD card for photo storage and a SIM card for message transmission.

“That camera had no markings on it, and it shook me up. I threw it in the truck and tried to go hunting, but all I could think of was how many more cameras were out there on my land. Hell, how could I have known right then, that months later, the Feds and TWRA would storm into my house and accuse me of stealing their property? Unreal, but it happened.”

The following afternoon, Hollingsworth accessed the memory card and found that over 1,000 photos of himself, family and friends (and TWRA officers entering his property) had been taken and transmitted. The earliest photos were dated Nov. 30, 2017, indicating the camera had been active for at least two months. The camera enabled round-the-clock monitoring of Hollingsworth, and TWRA was aware each time he entered or exited his land.

On the morning of Sept. 7, 2018, months after finding the camera, Hollingsworth was finishing breakfast when USFWS and TWRA officers surrounded his property and ordered to him to open the front door. “They were armed with all kind of guns, extra clips, first aid kits, and bulletproof vests—all to get the same game camera they snuck onto my land.”

(Farm Journal asked USFWS for comment on Hollingsworth v. TWRA and the search of Hollingsworth’s residence related to the game camera. In addition, Farm Journal asked for USFWS’ perspective on the Open Fields doctrine. USFWS declined comment on the entirety: “…we have no comment regarding this matter.”)

Hollingsworth was hit with hunting violations related to dove baiting, and also charged for theft of the trail camera in August 2019. Flatly stated, Hollingsworth believes the government was hunting a bullfrog with a shotgun. “I ended up with my first conviction for hunting over bait. I paid $5,000 for a lawyer and a $3,000 fine, lost my hunting license for three years, and missed a week of work. I’m not innocent of everything and I’m not above the law, but this was so heavy-handed and over the top, and I pleaded because I was in a headlock. They threatened me with jail time and hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines when in reality, I was railroaded over a camera.”

Ironically, the announced entry and search of Hollingsworth’s home required a warrant; the secret entry and hidden search of Hollingsworth’s private land required no warrant. The distinction is a capsule version of the Open Fields doctrine.

Hollingsworth filed a complaint (Hollingsworth v. TWRA) over the game camera in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Tennessee Eastern Division, alleging violation of his constitutional rights, and on Oct. 21, 2019, Judge S. Thomas Anderson dismissed Hollingsworth’s suit, partially due to reliance on the Open Fields doctrine.

Bottom line, a federal judge told Hollingsworth he had no reasonable expectation of privacy on his farm, and that his Fourth Amendment rights were not violated by TWRA’s trespass and camera installation. Anderson wrote: “It follows that Defendants (TWRA) mounted the camera in what can only be described as ‘open field,’ an area beyond the scope of the Fourth Amendment’s protections. Without some particular allegation to show that Defendants conducted a warrantless search of his home or the curtilage of the home, Plaintiff has failed to allege a Fourth Amendment violation.”

Despite Anderson’s ruling, Hollingsworth is adamant: Secret surveillance is “gut-level” wrong. During the duration of the camera’s presence, he drove by it countless times and discovered the device by pure chance—a fluke. No matter how much time goes by, Hollingsworth can’t shake persistent questions about more cameras. “How many others were on my land? How many are there now? Why not movie cameras? Listening devices? They’re apparently allowed to do all this by the U.S. Constitution anytime they feel like it, so where does it end? They’re allowed to film wives, daughters, girlfriends in areas where privacy is assumed?”

“Let It All Hang Out”

Atop the pile of similarities shared between the Rainwaters and Hollingsworth cases, sits a benchmark factor: TWRA’s original trespasses had no warrant and no probable cause. Thus far, SCOTUS has excused such federal action under the Fourth Amendment, but IJ attorney Windham contends Open Fields is in direct conflict with the state constitution.

“The purpose of Article I, Section 7 of the Tennessee Constitution is to protect the right of people to be secure in their private property,” he says. “You are not secure in your property if state officers can enter your land, wander around, and record video footage of you and your private activities without a warrant. The same should also be true under the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, but that’s a fight for another day.”

Again, under Open Fields, surveillance possibilities, particularly aided by digital technology, are increasingly invasive, and bound to expand as technological capabilities grow in tandem. Drones, live footage, powerful listening devices, virtual stakeouts and more were once the realm of sci-fi, but now must be reckoned as part of the Open Fields package.

“The Fourth Amendment is notoriously slow in catching up with technology,” says Mutnick, the attorney with Winslow & McCurry. He expects the Open Fields doctrine to gain more attention in the near-future, partially spurred by a rapid increase in surveillance tech. “Open Fields has basically been untouched by the Supreme Court since 1984, but think about the expanse of digital capability since the 1980s.”

Under Open Fields, any type of search on private land is legal, Windham says: “Any reasonable person out there recognizes the danger in allowing the government such power. The vast majority of us share a basic American understanding that private means private. We’re challenging TWRA’s initial entry of the properties and installation of the cameras, and there’s no evidence of a warrant for those searches. The positive news is that we have state constitutions. Even though TWRA thinks it has authority, we’re saying TWRA must follow the Tennessee Constitution and none of this is OK.”

Without accountability, the ability of a government official to monitor a private citizen, at will, is rife for abuse, Windham continues. “TWRA should have to get a warrant for these searches, plain and simple. You need an objective judge to consider each case and decide whether it makes sense for officers to enter private property. Otherwise, you have officers making decisions in the field, possibly based on their own subjective feelings or motivations, about when and how to search people’s private property.”

Without accountability, the ability of a government official to monitor a private citizen, at will, is rife for abuse, Windham continues. “TWRA should have to get a warrant for these searches, plain and simple. You need an objective judge to consider each case and decide whether it makes sense for officers to enter private property. Otherwise, you have officers making decisions in the field, possibly based on their own subjective feelings or motivations, about when and how to search people’s private property.”

“I want to reiterate the significance of what is happening to Tennesseans on their private land,” Windham concludes. “This is about so much more than hunting or cameras. This is about the basic right of every Tennessean for privacy on their own property. Terry and Hunter are standing up for that right. They want the surveillance to end—on their land and everywhere else.”

As for Rainwaters and Hollingsworth, the pair is in agreement: The marriage of privacy and property rights is currently neglected by SCOTUS, but state constitutions must protect the union.

“I’m forced to assume I’m being watched on my land right now and it’s an awful feeling; just like the worst feeling in the world,” Rainwaters describes. “People hear the story and at first they can’t believe it’s happened, but I think the public should know about every detail of what their officials are doing in secret; let it all hang out for everyone to see.”

Hollingsworth echoes Rainwaters’ sentiments, and adds punctuation: “I’m so glad the Institute for Justice has helped us, otherwise we’d never have the resources to fight. This whole deal has made me so paranoid, and I find myself constantly checking for cameras or listening devices. Are we still in America? They get to put up secret cameras on our land and get live photos of what we’re doing, and that’s protected by the Constitution? There’s something fundamentally wrong with this whole picture.”

(Again, Farm Journal asked TWRA for comment on Hollingsworth v. TWRA; the search of Hollingsworth’s residence related to the game camera; and the current Rainwaters-Hollingsworth v. TWRA case. TWRA declined comment on the entirety: “The Agency cannot comment on matters in litigation, nor can we provide comment on issues that are currently being litigated.” TWRA directed all questions to the Tennessee Attorney General’s office, but the AG office declined comment.)

For more, see:

Descent Into Hell: Farmer Escapes Corn Tomb Death

A Skeptical Farmer’s Monster Message on Profitability

Farmer Refuses to Roll, Rips Lid Off IRS Behavior

Rat Hunting with the Dogs of War, Farming’s Greatest Show on Legs

Killing Hogzilla: Hunting a Monster Wild Pig

Shattered Taboo: Death of a Farm and Resurrection of a Farmer

Frozen Dinosaur: Farmer Finds Huge Alligator Snapping Turtle Under Ice

Breaking Bad: Chasing the Wildest Con Artist in Farming History

The Great Shame: Mississippi Delta 2019 Flood of Hell and High Water

In the Blood: Hunting Deer Antlers with a Legendary Shed Whisperer

Farmer Builds DIY Solution to Stop Grain Bin Deaths

Corn Maverick: Cracking the Mystery of 60-Inch Rows

Blood And Dirt: A Farmer’s 30-Year Fight With The Feds

Against All Odds: Farmer Survives Epic Ordeal

Agriculture’s Darkest Fraud Hidden Under Dirt and Lies

From agweb.com