The World Health Organization Was Against Quarantines Only Last Year

Irecommend to you a document written in saner times, and published by the World Health Organization: “Non-pharmaceutical public health measures for mitigating the risk and impact of epidemic and pandemic influenza.” It came out in 2019. I’ve embedded it below.

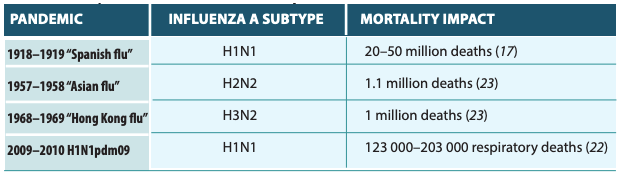

When the document says influenza, it is referring to any influenza-like infection which is inclusive of COVID-19; that is, any pandemic virus that happens to come along. In the last 100 years, they give examples of four prior to the current virus.

The point of the report is to examine a series of what are called non-pharmaceutical interventions, which can cover the full range of strategies of disease control, from hand washing to surface cleaning to mask wearing to quarantines to travel restrictions. The document contains both good and regrettable material, both of which are covered below. But the standout points for us today are that the World Health Organization only last year solidly recommended against quarantines even if it is only limited to the exposed and sick.

It never even considered the notion of universally locking down an entire population. In that sense, it is an improvement over current practice, and evidence that governments around the world threw out long-standing law and tradition in a disease panic, shattering human relationships and the global economy.

That said, a major problem with the document is its overly formal approach that seeks to model disease severity and government response.

The pandemic influenza severity assessment (PISA) framework was introduced by WHO in 2017. The severity of an influenza epidemic or pandemic is evaluated and monitored through three specific indicators: transmissibility (referring to incidence), seriousness of disease, and impact on health care system and society. The severity is categorized into five levels: no activity or below seasonal threshold, low, moderate, high or extraordinary. The PISA framework is being tested and improved during seasonal influenza epidemics; the aim is to help public health authorities to monitor and assess the severity of influenza, and to inform appropriate decisions and recommendations on interventions.

Almost everything here rests on the ability to discern and model disease severity in real time. The trouble is that we have to make the judgement call in the midst of this pandemic. Dr. Fauci in late February wrote that “the overall clinical consequences of Covid-19 may ultimately be more akin to those of a severe seasonal influenza.” By WHO standards, that would qualify as “moderate.”

A few weeks later, fear of hospital bed shortages and a lack of ventilators caused that assessment to change. In a few short days, we moved from thinking this was a seasonal problem to treating it as the most severe pandemic since 1918, and it’s not really clear why. The more we know about the virus, the more we realize that Fauci’s original assessment was closer to the truth, especially when considering how it targets especially those with very low life expectancy, exactly as John Ioannidis predicted on March 7.

Deciding whether and to what extent non-pharmaceutical interventions might be necessary is easily modelled on paper but far more difficult to assess in real time. Everything is clear looking backwards. We can know what we need to know about managing the pandemics of 1968, 1957, 1948-51 (during which times government did almost nothing and left disease mitigation to the professionals), and 1918, when some governments used powers condemned by medical professionals later.

But planning backwards in time is not what the WHO proposed last year. They expected high-end health professionals to become central planners in real time, in the midst of enormous confusion over data. It’s just not possible to do that. Empowering governments with the responsibility to make such extra decisions over people’s lives and freedom might not be the wisest route to take.

Nonetheless, there is a fairly large gap between what the WHO recommended in 2019 and what governments actually did in 2020.

Consider their 2019 recommendations:

Hand hygiene

Hand hygiene is recommended as part of general hygiene and infection prevention, including during periods of seasonal or pandemic influenza. Although RCTs have not found that hand hygiene is effective in reducing transmission of laboratory-confirmed influenza specifically, mechanistic studies have shown that hand hygiene can remove influenza virus from the hands, and hand hygiene has been shown to reduce the risk of respiratory infections in general.

Respiratory etiquette

Respiratory etiquette is recommended at all times during influenza epidemics and pandemics. Although there is no evidence that this is effective in reducing influenza transmission, there is mechanistic plausibility for the potential effectiveness of this measure.

Face masks

Face masks worn by asymptomatic people are conditionally recommended in severe epidemics or pandemics, to reduce transmission in the community. Disposable, surgical masks are recommended to be worn at all times by symptomatic individuals when in contact with other individuals. Although there is no evidence that this is effective in reducing transmission, there is mechanistic plausibility for the potential effectiveness of this measure.

Surface cleaning

Surface and object cleaning measures with safe cleaning products are recommended as a public health intervention in all settings in order to reduce influenza transmission. Although there is no evidence that this is effective in reducing transmission, there is mechanistic plausibility for the potential effectiveness of this measure…. The effectiveness of different cleaning products in preventing influenza transmission – in terms of cleaning frequency, cleaning dosage, cleaning time point, and cleaning targeted surface and object material – remains unknown.

Ventilation of rooms

Increasing ventilation is recommended in all settings to reduce the transmission of influenza virus. Although there is no evidence that this is effective in reducing transmission, there is mechanistic plausibility for the potential effectiveness of this measure.

Contract tracing

Active contact tracing is not recommended in general because there is no obvious rationale for it in most Member States. This intervention could be considered in some locations and circumstances to collect information on the characteristics of the disease and to identify cases, or to delay widespread transmission in the very early stages of a pandemic in isolated communities.

Voluntary Isolation

Voluntary isolation at home of sick individuals with uncomplicated illness is recommended during all influenza epidemics and pandemics, with the exception of the individuals who need to seek medical attention. The duration of isolation depends on the severity of illness (usually 5–7 days) until major symptoms disappear.

Quarantine of Exposed People

Home quarantine of exposed individuals to reduce transmission is not recommended because there is no obvious rationale for this measure, and there would be considerable difficulties in implementing it…. As with isolation, the main ethical concern of quarantine is freedom of movement of individuals. However, such concern is more significant for quarantine… Mandatory quarantine increases such ethical concern considerably compared with voluntary quarantine. In addition, household quarantine can increase the risks of household members becoming infected.

School closings

School measures (e.g. stricter exclusion policies for ill children, increasing desk spacing, reducing mixing between classes, and staggering recesses and lunchbreaks) are conditionally recommended, with gradation of interventions based on severity. Coordinated proactive school closures or class dismissals are suggested during a severe epidemic or pandemic. In such cases, the adverse effects on the community should be fully considered (e.g. family burden and economic considerations), and the timing and duration should be limited to a period that is judged to be optimal.

Workplace Closures

Recommendation: Workplace measures (e.g. encouraging teleworking from home, staggering shifts, and loosening policies for sick leave and paid leave) are conditionally recommended, with gradation of interventions based on severity. Extreme measures such as workplace closures can be considered in extraordinarily severe pandemics in order to reduce transmission.

Avoiding crowding

Avoiding crowding during moderate and severe epidemics and pandemics is conditionally recommended, with gradation of strategies linked with severity in order to increase the distance and reduce the density among populations.

Travel

No scientific evidence was identified for the effectiveness of travel advice against pandemic influenza; however, providing information to travellers is simple, feasible and acceptable…. Entry and exit screening for infection in travellers is not recommended, because of the lack of sensitivity of these measures in identifying infected but asymptomatic (i.e. presymptomatic) travellers.

Border closure

Border closure is generally not recommended unless required by national law in extraordinary circumstances during a severe pandemic, and countries implementing this measure should notify WHO as required by the IHR (2005).

So there you have it. As for universal quarantine, stay at home orders for people who are not infected, strict and legal distinctions between essential and nonessential businesses, blanket shutting down of bars and restaurants and theaters, mandatory 12-week quarantines of all people, mandatory mask wearing for everyone, or strict and measured rules on human separation, we see none of this anywhere in this document.

By comparison to what we’ve been through, this is a very unrestrictive document. And more recently, the WHO even recommended Sweden’s more liberal approach that completely avoid extreme measures.

The real problem is epistemic: who is to decide what is normal, mild, moderate, or severe pandemic? Leave that decision to politicians and bureaucrats, and you have a problem. They do not know, and, as we’ve seen, immediately adopt the most extreme measures and go beyond them, contradicting the warning issued by 800 medical professionals on March 2, 2020.

Government is not an institution ideally suited for disease assessment or control.

Edward Peter Stringham is President of the American Institute for Economic Research, Davis Professor of Economic Organizations and Innovation at Trinity College, and Editor of the Journal of Private Enterprise. He is editor of two books and author of more than 70 journal articles, book chapters, and policy studies. His work has been discussed in 15 of the top 20 newspapers in the United States and on more than 100 broadcast stations including MTV. Stringham is a frequent guest on BBC World, Bloomberg Television, CNBC, and Fox. Rise Global ranks Stringham as one of the top 100 most influential economists in the world. He earned his B.A. from College of the Holy Cross in 1997, his Ph.D. from George Mason University in 2002. His book, Private Governance: Creating Order in Economic and Social Life, is published by Oxford University Press.

From aier.org