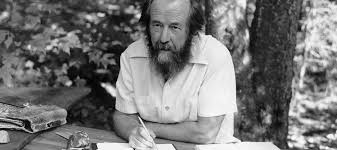

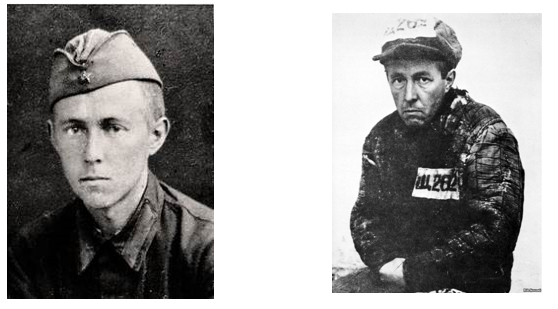

Alexander Solzhenitsyn (and Leonid Svetlov)

By Rob Chase

Once upon a time in a 1970’s Summer I decided to read the Russians. I knew Russian literature had to be dreary and cold so what better time than Summer to start? I had seen the movie Doctor Zhivago several times and decided to read the Boris Pasternak novel it was based on. I enjoyed it very much. I went on to read Brothers Karamazov which I also loved. I tackled War and Peace, but does anybody ever finish War and Peace?

I did find a shorter Russian novel by Alexander Solzhenitsyn who was starting to gain some Cold War name recognition as a Soviet dissident. The novel was “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” The title itself will explain why it is a short read, but it is about a political prisoner in the Soviet Gulag political prisons after World War 2, when the paranoid Soviet Dictator Joseph Stalin rewarded the bravery of his Red Army soldiers by incarcerating anyone suspected of disloyalty, even if presumably innocent.

The story’s character, Ivan Denisovich, was autobiographical of Solzhenitsyn’s post war experience. In real life Front Line Officer Solzhenitsyn was critical of the rape and pillage by Russian soldiers of German civilians, and was therefore suspect of being dangerous to Stalin.

In the story Ivan Denisovich barely survives starvation while laboring long hours in the work camps.

How could such a colorful culture like Old Russia of the Romanov’s fairy tale palaces, stylish military uniforms, and the Czar’s attractive daughters become so dreary and gray?

After the evil tyrant Stalin died in 1953 there was a “Stalin Thaw.” Russians had to admit Stalin had caused more devastation to the Soviet Union than even Hitler had.

New Soviet Premier Nikita Kruschev had survived the Stalin purges because he had the gift of getting Stalin to laugh. Who wants to kill their clown? Kruschev survived and succeeded Stalin and Russians could breathe a sigh of relief. Out of the fire back into the frying pan.

Shortly after the time of my reading of Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s short novel, the now deported gadfly gave his famous Harvard Address “A World Split Apart — Commencement Address Delivered At Harvard University, June 8, 1978” which I also read. I was only in my twenties but I recognized here is a guy who knows something about freedom because he lived without it for so long.

I will get back to “A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” later in this article.

Solzhenitsyn went on to publish many more books documenting the horrors of the prison camps in the Soviet Union. He received the Nobel Prize for literature in 1970, but didn’t physically receive it until 1974 after he had been expelled from his Homeland.

The experiences in the Gulag brought Solzhenitsyn to seek spiritual solutions, Christianity in particular. He was to reflect on the official state religion of atheism:

“Over a half century ago, while I was still a child, I recall hearing a number of old people offer the following explanation for the great disasters that had befallen Russia: “Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.’ “Since then I have spent well-nigh 50 years working on the history of our revolution; in the process I have read hundreds of books, collected hundreds of personal testimonies, and have already contributed eight volumes of my own toward the effort of clearing away the rubble left by that upheaval. But if I were asked today to formulate as concisely as possible the main cause of the ruinous revolution that swallowed up some 60 million of our people, I could not put it more accurately than to repeat: ‘Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.”

I remember reading his famous “Harvard Address” in 1978, and was impressed with what he had to say, although at that point in my life I was still soul searching for truth.

Below are some quotes from his Harvard Address which had meaning for that time, and even more so today. I will let the quote speak for themselves:

“The anguish of a divided world gave birth to the theory of convergence between the leading Western countries and the Soviet Union. It is a soothing theory which overlooks the fact that these worlds are not evolving toward each other and that neither one can be transformed into the other without violence. Besides, convergence inevitably means acceptance of the other side’s defects, too. And this can hardly suit anyone.”

“A decline in courage may be the most striking feature that an outside observer notices in the West today. The Western world has lost its civic courage, both as a whole and separately, in each country, in each government, in each political party, and, of course, in the United Nations. Such a decline in courage is particularly noticeable among the ruling and intellectual elites, causing an impression of a loss of courage by the entire society. There are many courageous individuals, but they have no determining influence on public life.”

“Must one point out that from ancient times a decline in courage has been considered the first symptom of the end?”

“When the modern Western states were being formed, it was proclaimed as a principle that governments are meant to serve man and that man lives in order to be free and pursue happiness.”

“Indeed, an outstanding, truly great person who has unusual and unexpected initiatives in mind does not get any chance to assert himself; dozens of traps will be set for him from the beginning. Thus mediocrity triumphs under the guise of democratic restraints.”

“This tilt of freedom toward evil has come about gradually, but it evidently stems from a humanistic and benevolent concept according to which man — is the master of the world.”

“The press has become the greatest power within Western countries, exceeding that of the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary.”

“Without any censorship in the West, fashionable trends of thought and ideas are fastidiously separated from those that are not fashionable, and the latter, without ever being forbidden have little chance of finding their way into periodicals or books or being heard in colleges.”

“… a selection dictated by fashion and the need to accommodate mass standards frequently prevents the most independent-minded persons from contributing to public life and gives rise to dangerous herd instincts that block dangerous herd development.”

“The mathematician Igor Shafarevich, a member of the Soviet Academy of Science, has written a brilliantly argued book entitled Socialism; this is a penetrating historical analysis demonstrating that socialism of any type and shade leads to a total destruction of the human spirit and to a leveling of mankind into death. Shafarevich’s book was published in France almost two years ago and so far no one has been found to refute it.”

“On the way from the Renaissance to our days we have enriched our experience, but we have lost the concept of a Supreme Complete Entity which used to restrain our passions and our irresponsibility.”

“We have placed too much hope in politics and social reforms, only to find out that we were being deprived of our most precious possession: our spiritual life.”

“If, as claimed by humanism, man were born only to be happy, he would not be born to die. Since his body is doomed to death, his task on earth evidently must be more spiritual: not a total engrossment in everyday life, not the search for the best ways to obtain material goods and then their carefree consumption. It has to be the fulfillment of a permanent, earnest duty so that one’s life journey may become above all an experience of moral growth: to leave life a better human being than one started it.”

“Is it true that man is above everything? Is there no Superior Spirit above him? Is it right that man’s life and society’s activities should be ruled by material expansion above all? Is it permissible to promote such expansion to the detriment of our integral spiritual life?”

“If the world has not approached its end, it has reached a major watershed in history, equal in importance to the turn from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. It will demand from us a spiritual blaze; we shall have to rise to a new height of vision, to a new level of life, where our physical nature will not be cursed, as in the Middle Ages, but even more importantly, our spiritual being will not be trampled upon, as in the Modern Era.

The ascension is similar to climbing onto the next anthropological stage. No one on earth has any other way left but — upward.”

Now back to “A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.” There was a character in the novel that stuck in my mind for years. In the midst of the gloom and suffering was a young Baptist Russian, Alyoshka, who had been sentenced for his Evangelism.

He is the bright light in the Camp sharing what little he had with others, is cheerful to everyone, and expects nothing in return. A candle in the dark. He gives Ivan some hope that there is a benevolent spiritual reality that transcends the Darwinistic struggle in the Camp.

I used to have a radio interview show on American Christian Network in Spokane from 2008 to 2012. I interviewed a lot of local luminaries, one of whom was Pastor Alex Kaprian of the Slavic Baptist Church in downtown Spokane. Alex grew up in the Ukraine and had been persecuted for his Christian Faith. Eventually, in the 1980’s, Alex led his flock to Spokane to seek freedom in America. One thing he told me in our interview was that, “you can never appreciate how precious freedom is until you don’t have it.”

After the interview we chatted and I told him about how deeply spiritual parts of “The Brothers Karamazov” were, and how ironic it was that a Country that had produced authors like Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy could become atheistic. I also mentioned how much the fictional character of Alyoshka impressed me in the short Solzhenitsyn novel.

Alex suddenly exclaimed, “He goes to our Church.”

“What?” I asked.

Alex explained, “There is a man named Leonid Svetlov who goes to our Church and he was with Solzhenitsyn in the Gulag, and the character of Alyoshka was patterned after him. Leonid had survived the Gulag and had come to Spokane in the 1980’s and joined the Slavic Baptist Church in Spokane.”

Alex went on to say Leonid was still alive but couldn’t speak English. Even so, Alex arranged an interview for my show with his wife and Church Youth Group leader to interpret. When I met Leonid he was like Alyoshka, warm-hearted, sparkling, and emanating an interior joy. I am not a hugger but at the end of our interview I embraced him. I couldn’t have been happier if I had had the chance to embrace any other character in the fictional books I had read that I had liked – maybe Tarzan or Doctor Doolittle for instance – but Alyoshka/Leonid was real, and 30 years after I met him in my mind through Solzhenitsyn’s book. I am not the hugging type, but I physically hugged Leonid.

I took the picture below in the studio, which doesn’t do Leonid justice. I wish I had taken more photos and especially one of us together, but I am still happy I met him. Leonid died a couple years ago but I look forward to our next meeting.