The Sunshine Mine Fire of 1972

By Rob Chase

Sometimes the spring sky can be blue, and the sun shines its welcome warmth on the land, and then suddenly a lightning bolt comes out of nowhere leaving sorrow and destruction that lingers on. I was 18 in 1972. A child born on May 2nd of 1972 would be into middle-age now.

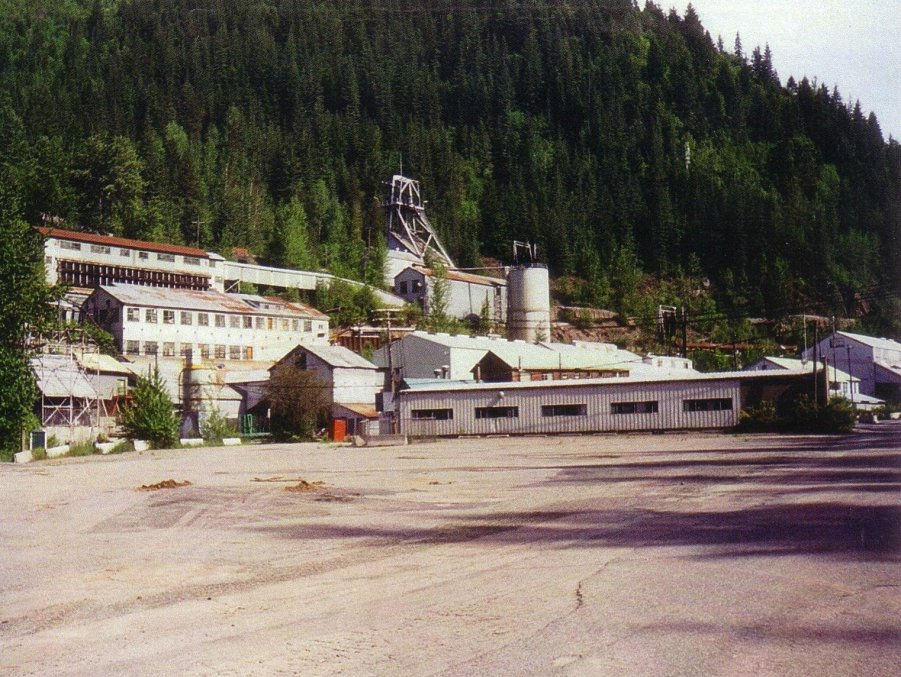

When I got home from school that day and walked up the driveway of our house in Big Creek Gulch, between Kellogg and Wallace, Idaho my mother was coming out of the garage in her car. She said “There’s a fire at the mine.” And then hurriedly left in her car, headed southward to the freeway. The Sunshine Mine where my father and cousin worked was only about half a mile up the road, so I decided to walk up there and see what was going on. Several cars passed me by and so did a KHQ Television truck.

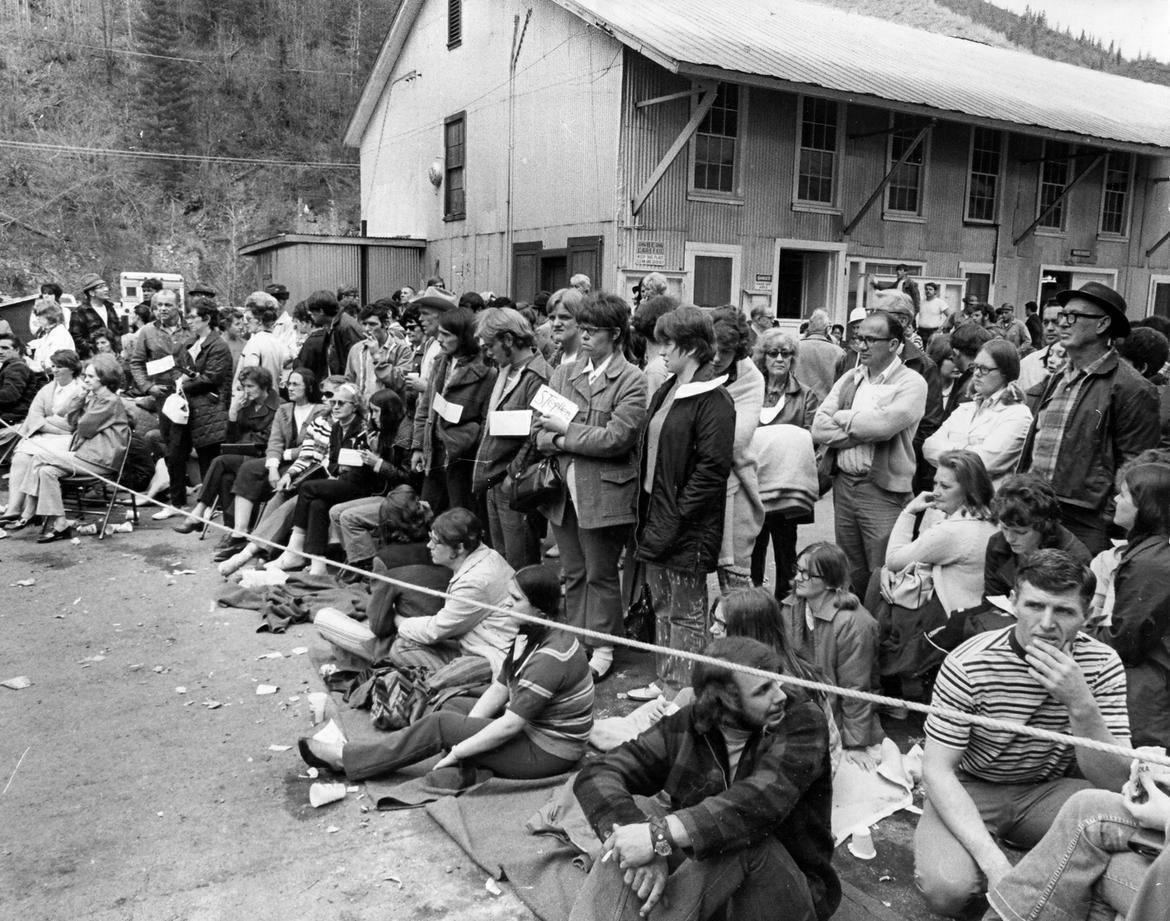

As I rounded the corner I saw a large crowd of people gathering. I started to worry and then I saw my cousin, Dan Klein, standing with a few of his miner friends in the parking lot across the creek from the mine. I walked up to him and he pointed to the opening of the Jewel Shaft. He said, “Just inside the Jewel Shaft there are five bodies.” He named the victims off but I especially remembered the name Bob Bush who was a foreman. I listened in shock as they talked about who was believed to be dead, who had escaped, and if there was any chance that anyone might still be alive in the Mine.

I had worked on the surface at the mine the previous summer, but I was never underground since you had to be 18 to go underground. I was hoping to hire on that summer after I graduated Kellogg High School, and to eventually spend a few years being a gyppo miner like my cousin, who made good money by contracting with the mine for the amount of ore removed.

Presently a man who I had worked with the previous summer came by and gave me a green hard hat to look official. He told me to stay on the bridge over the creek and keep everyone out who didn’t belong there because the Press had been slipping through and interviewing surviving miners, and the missing miners wives and children who were being allowed into the Red Cross station that was hastily being setup. I already knew pretty much everyone who had any business there since I had met many of them through my father, Marvin Chase, who was the Mine Manager. As soon as I could, I volunteered to go on Mine Rescue to do what I could. I passed the quick physical and was ready to go but my mother intervened since our family was receiving threats, and she wanted me to stay with my father. I did so throughout the nine day ordeal, except when he went home to sleep or I wasn’t allowed into a meeting. In that case I helped out at the Red Cross Station and handed out donated coffee and cigarettes.

The first night I saw our Spanish Teacher, Elizabeth Fee, pacing around. I think she was smoking nervously but I mostly remember the grief on her face. She had been recently widowed. I walked over to her and said hello. I didn’t get any farther. “Have you heard anything about my son Norman?” I said I didn’t know she had a son but I would let her know if I heard anything. She began to weep and I didn’t know what to do but put my arm around her. Through her tears she told me that as a little girl in Butte her father worked at a mine which had a fire and almost everyone underground had died. We prayed together and then I left.

When I got home my cousin was there. I asked him if he knew anything about a Norman Fee. He told me one of the miners he had spoken to said he saw Norman Fee die. I didn’t tell Mrs. Fee.

I moved to Kellogg from Seattle in 1969. I loved the outdoors and the friendly kids compared to the density and urban culture of Seattle. My father had always been in mining but took a job at Boeing in 1959 for ten years. Our move to Kellogg was the greatest thing that had ever happened to me until the Fire. My mother remarked that night that we would never be the same again.

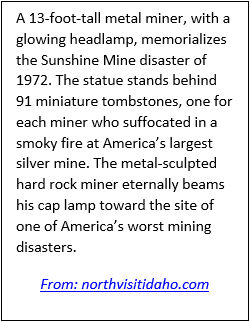

Over the ensuing seven days the crowd dwindled as bodies were found and families went home to mourn and bury their dead. My cousin was on Mine Rescue and he told me of men whose bodies were found collapsed running from the smoke and carbon monoxide. Some died so quickly they were still sitting at lunch tables, and one foreman was found standing against a wall with the phone connected to the surface still in his hand. The bodies were unrecognizable in the degenerative atmosphere of moisture and heat. The ravens circulating over the exit airflow shaft on the hill above the mine were noticeable, but never mentioned.

The rescue attempt for possible survivors was a joint effort of Mine Management, especially Safety Engineer Bob Launhardt, the Federal and State Bureau of Mines, and lots of assistance from neighboring mines, and others all across the USA and Canada. A plan was devised to lower a rounded rescue cage through the air shaft to the 3700’ level where there was the possibility miners might have found fresh air. The entire story is chronicled in the Deep Dark: The Deep Dark: Disaster and Redemption in America’s Richest Silver Mine

Against all odds two miners were discovered still alive, Ron Flory and Tom Wilkinson. They had stayed by the fresh air and not strayed far except to collect the lunch buckets of less fortunate miners. We were at the Mine Office when my father told us the news that they had been found. My mother asked him who the two miners were and we left the office. At the same time their two wives had just driven up together and they had their name tags on. My mother couldn’t control herself and immediately told them. They screamed in delight and ran up to the mine to tell their relatives. Later that day the miners were brought up in the rescue cage through the Jewel Shaft, and walked out alive. In what was left of the crowd one of the Pastors accompanying the families struck up the song, “Praise God from Whom all Blessings Flow.” Everyone sang together and it was another rare light in the darkness. There was renewed hope among the families still remaining.

The routine for breaking the news to families was that Pastors or people who were close to the families were told when a fallen miner had been identified, and they would break the news to the family, who would then go home.

On the ninth day the rescue attempts had come to a conclusion. My father always called a Press Conference after the families had been notified and updated the number of dead found, the number still missing, and then report on status and any progress that had been made. He held his final Press Conference and announced the search was over and the last bodies had been recovered. His voice cracked as he told the small crowd it was “best for everyone to go home now.” I will never forget the screams of anguish from families who had been holding on with hope for nine days and that hope was gone.