Tropico 5: The Game That Proves Central Planning Can’t Work

Tropico demonstrates to us that despite our best intentions, it is hubris to believe we can mold our economy to our wishes through central planning.

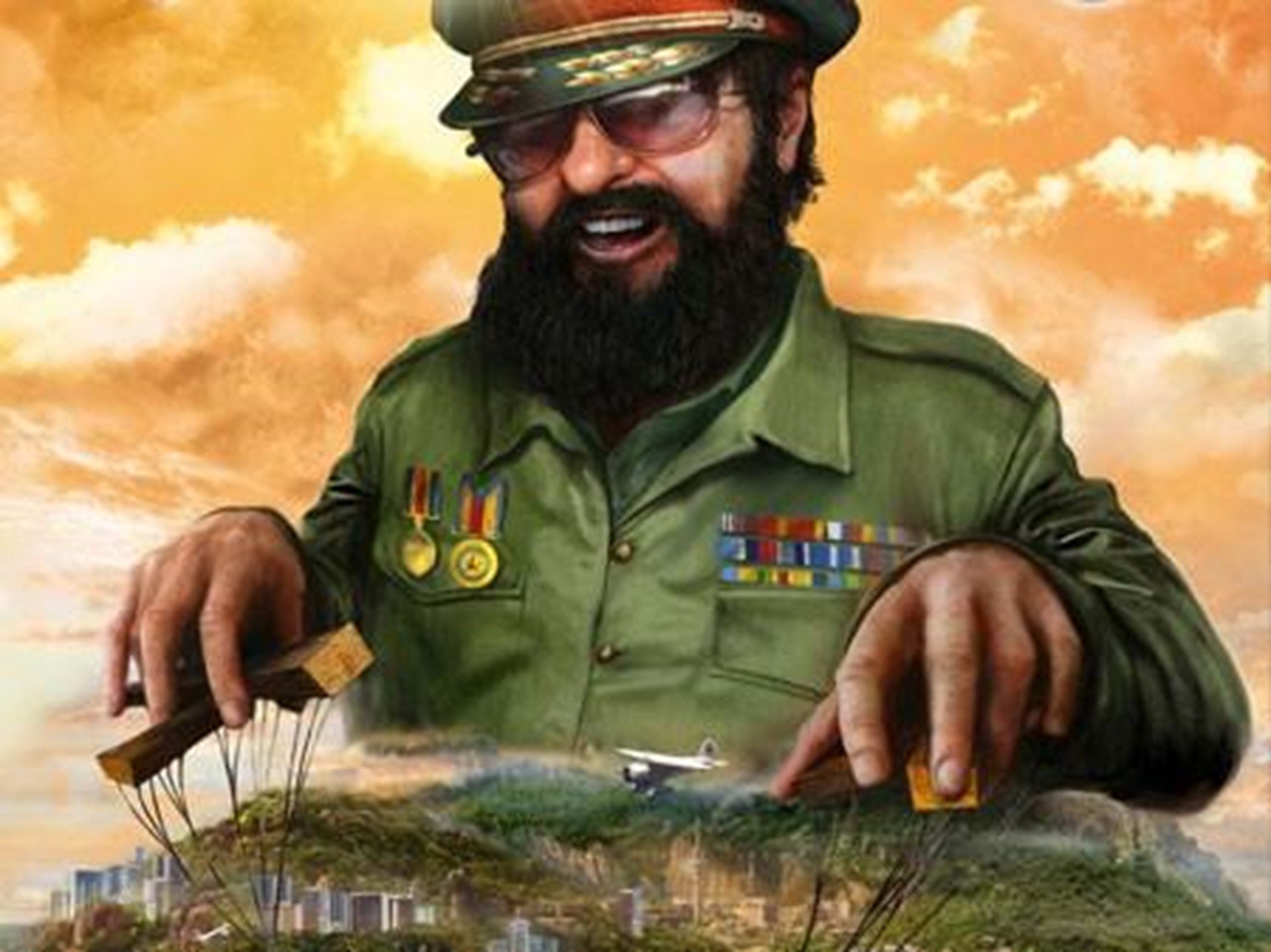

In Tropico 5, you are El Presidente—the leader of a Caribbean island that is a semi-democratic banana republic. Your primary objective is to preserve your rule by micromanaging your country’s economy to appease your citizens, the Tropicans. If they are dissatisfied with your rule, they can vote you out in the next elections or stage a coup d’état, costing you the game.

First released in 2001, the city-building and management game has sold millions of copies worldwide, and the sixth installment is scheduled for release later in 2019. The game was even banned in Thailand due to concerns it would stir social unrest. In a hilarious response, the game developers included a mission in its DLC (downloadable content) to steal away tourists from Thailand.

Tropico 5 presents an engaging platform for players to craft their socialist paradise and examine the mechanics of socialist economies. Apart from sandy beaches and skyscrapers, Tropico 5’s appeal arises from loading players with a swarm of decisions to make, each with certain trade-offs that must be accounted for. Since most of us formulate our ideals from an armchair perspective, Tropico 5 delivers a much-needed dose of reality and numerous lessons on economics for its players to reflect upon.

Pineapples, Cotton, or Death

Players have to plan out their nation’s agricultural sector meticulously, including making decisions about agricultural produce, location, technology, and farm employment.

The first focus when you start up the Tropico 5 game is managing your agricultural sector. Players must choose between constructing two types of farms. Farms producing food crops for local consumption, such as bananas and pineapples, boost your approval rating but don’t add income to your budget. Conversely, farms growing economic crops such as tobacco and cotton bring a healthy income stream but don’t feed your people.

Some players prefer to amass large sums of wealth in the early game through cotton exports and then focus on food production later, hopefully before too many people starve to death. Other players risk bankruptcy in their attempt to bring their popularity to a safe level by spamming pineapple plantations before transitioning to economic crops later. Either way, you’re stuck between a rock and a hard place.

A Wager on Wages

Wages must also be manually assigned in Tropico. Intuitively, some players inflate wages for jobs such as teachers and scientists, which require a higher level of education.

Buckling down on an education-based wage system causes a mass exodus of workers deserting lower-paying agricultural jobs, threatening your domestic food supply.

However, buckling down on an education-based wage system causes a mass exodus of workers deserting lower-paying agricultural jobs, threatening your domestic food supply. Conversely, if wages for white collar jobs are not high enough, Tropicans will not bother to upgrade their education to take on those jobs, crippling your economic growth and funding for programs such as food and healthcare subsidies to appease your people.

Spontaneous Order

An article written by The Daily Beast sums up my views on the lessons we can take from Tropico:

“The level of micromanagement needed to skillfully run the island is not impossible to acquire, but it becomes clear why no sane country is run this way. There is no mechanism to allow for wages to be set organically and there is too much onus on single individual (El Presidente) to guide the nation. Great for a game, terrible as a template for real life.”

The alternative to all the insane micromanagement of central planning already exists—it’s called the free market.

In a free market, transactions are voluntary, and they produce market prices that guide the decisions of consumers and firms. As economist Alex Tabarrok aptly describes it, prices are “a signal wrapped up in an incentive.” When there is scarcity of food, prices will naturally rise to signal shortages even without the supervision of government bureaucrats. The expectation of larger profits invites firms to build more pineapple farms and raise wages sufficiently for pineapple farmers to attract enough labor. While not foolproof, market prices must remain free so that prices can adjust organically as our economy evolves.

Applying Tropico’s Lessons to the Real World

Unfortunately, many governments worldwide operate as if they are playing Tropico, without a second thought about manipulating the economy through central planning.

In Venezuela, the socialist government’s game of Tropico has failed its people. Despite having the world’s largest oil reserves, Venezuelans struggle desperately for basic amenities and even have to purchase rotten meat in markets to survive.

To support its massive social welfare programs, the government nationalized oil production, and petroleum exports account for 95 percent of the nation’s total exports, making the economy hyper-sensitive to shocks in oil prices. Just like Tropico players who focus too much on banana or cotton plantations, Venezuela was doomed when it funneled all its resources into oil production.

Centrally planned economies typically lack economic diversification since governments actively prioritize certain industries by injecting investment funds and nationalizing companies. Thus, these economies are afflicted with Dutch Disease—an economic term describing a decline in overall market competitiveness due to over-reliance on certain industries.

However, the Venezuelan government still hasn’t finished its game of Tropico. To appease Venezuelans, it raised the minimum wage 34 times from previous levels and imposed strict price controls on essential goods like cooking oil and flour. As a result, the currency became hyper-inflated and worthless, destroying incentives for firms to keep producing essential goods.

Failure to Plan

Some may remark that what happened in Venezuela is merely the product of government corruption, and the solution is more central planning but done better.

Unfortunately, Tropico has demonstrated to us that despite our best intentions, it is hubris to believe we can mold our economy to our wishes through central planning. One must realize that the government is neither omniscient nor omnipotent; it simply cannot define or defy economic realities. As the great economist Milton Friedman once said, “If you put the federal government in charge of the Sahara Desert, in 5 years there’d be a shortage of sand.”

While not foolproof, it is ultimately market prices that have successfully advised millions of businessmen worldwide in creating and delivering products that make our lives meaningful at prices we can afford. Marketplaces are crucial experimental spaces for firms to discover how best to serve their consumers only if prices are liberated from the chokehold of government manipulation.

Perhaps failing to plan is not planning to fail.

Image credit: Tropico

From: fee.org